Sickness and the supernatural

Ken Macintyre, Research anthropologist, compiled from field notes 1997

KETEMUK: AN ILLNESS CAUSED BY JINNS AND OTHER SPOOKY THINGS

Ketemuk was one of the most commonly diagnosed conditions in the Sasak villages we visited between 1992 and 1997 in Western Lombok. Ketemuk simply means ‘entry (of a spirit)’ or to be touched by a supernatural agent or a returning ancestral spirit.

Ketemuk commonly occurs when an individual unknowingly touches a member of the ubiquitous jinn community that inhabits the invisible parallel world of every Sasak village in Lombok. Nowadays it is the view of elderly Sasak people that owing to the relaxation of social constraints and restrictions on young people, especially in their movements within and around the village, they are in constant danger of being infected by all manner of dangerous supernatural agents in particular the jinns. As my informant Amaq Jamali commented:

‘In the old days parents taught their children where they could go safely in and around the village and they were not allowed outside the house after magrib (sunset). There were strict rules (adat) in those days to stop children getting ketemuk.’

The symptoms of ketemuk are many and varied and can range from a simple headache to serious physical and psychiatric symptoms. The most common indications are dingin teleh (fever), puyeng (headache), baduk (stomach ache) and pengot (facial paralysis). Some forms of ketemuk can cause severe illness or the sudden onset of geremon (delirium) and jogang (insanity) that may lead to death if not properly treated.

Diagnosis of Ketemuk

Shamanistic healers known as belian batin or belian jinn customarily diagnose severe cases of ketemuk. These practitioners have a wealth of experience in detecting the various common and subtler symptoms that can manifest as this disease. If there is the slightest doubt as to the causative agent responsible for a ketemuk, the belian will prepare mamaq a betel nut quid made from the contents of the andang (literally meaning ‘in front’) provided by the client. The upfront provision of medicine in the form of the andang was a customary requirement (sarat) that must be observed before visiting a belian or traditional healer. Nowadays andang is regarded as a payment for service and usually involve gifts of food and/or money.

The practitioner prepares a quid of betel nut. He assembles a mixture of kanjul (betel nut, Areca catechu), apuh (slaked lime) and lekes (the fresh leaf of the Piper betel vine). He chews the concoction while intently focusing his mind on his client’s disorder for a period of approximately fifteen minutes.3 It is believed that during this time he makes contact with the supernatural agent that gave rise to his client’s suffering. At the conclusion of his rumination, he removes the masticated remnants of the betel chew from his mouth and places it on a fresh betel leaf (see Figure 1). He then examines it closely to discover the origin of the client’s illness.

If the betel remnants are bright red and translucent, his diagnosis indicates a jinn induced ketemuk; if it is pink and opaque, it indicates a ghost or ancestral spirit to be the culprit, whereas if it is red and streaky, the prognosis is a clear case of guna-guna (black magic or sorcery). If the remnant shows unfamiliar patterns and colours, this may indicate some other supernatural aetiology, such as belis (Satan) and may indicate the need for further investigation. In some instances where the masticated betel fails to indicate an identifiable diagnosis, the belian will package the chewed remnants into a fresh betel leaf (lekoq) and request the client to place it under their pillow and to return it early the next morning for further examination. Once a diagnosis has been determined, the masticate betel remnants are retained and employed as a sembeq or protective shield at the conclusion of treatment.

Treatment of Ketemuk

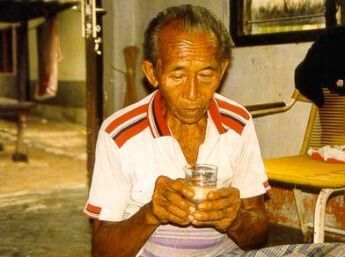

Traditional treatment for ketemuk begins with the sufferer receiving a glass of water into which the belian spits a small quantity of saliva and subvocalises a jampi or spell. In the modern day setting the utterance is not a spell but rather a doa – a prayer or passage from the Koran. Once the water has been blessed, it is transformed into a powerful medicine known as aiq jampi or seseru.

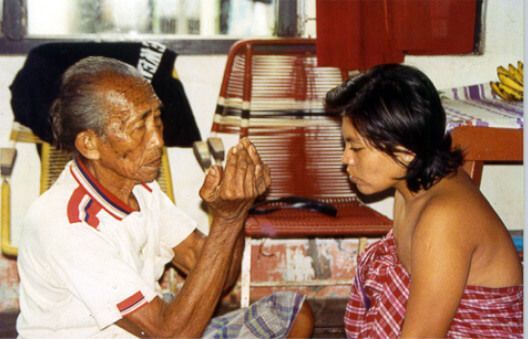

The patient receives an intensive head, neck and shoulder massage known as popot (see Figures 3-7). During this treatment the belian will spit (peru) and blow the pungent vapours of either turmeric or garlic onto the client’s neck, shoulder and thoracic region and this action is interspersed by a potent spell or jampi by the practitioner (see Figure 3 opposite). This ritual is believed to invoke the malign illness-causing agent to vacate the client’s body. According to Amaq Jamali the omnipresent jinn is the most common cause of ketemuk at the village level. It is repelled by acrid odours (garlic or turmeric) and salt. Saltwater baths were once a traditionally used method of treating ketemuk cases.4

Raw salt is still used as a deterrent for jinns in and around villagers’ houses.

Jamali commented that potent massage strokes to the client’s shoulder, neck and head drive the malicious spirits towards the top of the head.

Towards the conclusion of the massage the belian firmly grasps a lock of hair from the crown of the client’s head (see Figure 7) in the region of the fontanelle between the frontal and parietal bones, twists the hair around his index finger, holds the tension for a few moments while subvocalising a jampi (spell) to invoke the unfriendly spirit to vacate the body. The belian then suddenly jerks the strands of hair upwards causing a popping sound (pertuk). For an instant the client looks stunned by the sudden upward jerking action. It is at this point that the belian is assured that the ketemuk has been expelled from the client’s body and informs his patient that his or her sickness has been removed.

To apply the final ministration, the belian inserts his thumb or middle finger into the remnants of the betel concoction and performs a sembeq, a red upward mark on the forehead of the patient. Depending on the severity of illness, the sembeq can vary in size from a small dot to a line from above the bridge of the nose to the hairline on the forehead (kening). In addition, if the illness is serious, a sembeq inenam is placed on the thumb of the patient’s right hand and the sembeq inen naeng on the large toe of the left foot, the direction always being from the outer part of the toes or finger upwards toward the body.5 The sembeq is believed to provide a protective medicinal shield that deters the ejected spirit from re-entering or reattaching itself to the victim’s body. It is the spell or jampi inherent in the sembeq that provides the potency of the medicine.

In cases where ketemuk is determined to be caused by a ghost, soul (roh) or returning ancestral spirit, the treatment is similar; however, rather than using the residue of the betel chew as a sembeq, the belian will use apuh or slaked lime as the sembeq. Apuh symbolises the bone and ghost-like remains of the body after death.6 The treatment of ketemuk involving a returned ancestral spirit can be highly dangerous, depending on how far back the particular ancestor is traced. There is a belief within traditional Sasak society (even to this day) that distant ancestors referred to as tetoak laek possess formidable magical powers which can, under certain circumstances, be used maliciously against those who unwittingly offend them as illustrated in the following case study.

In 1997 my informant Bado related an incident that had happened to his one-year-old daughter. The child suddenly developed keipaq pengot (facial paralysis) marked by the dropping of her jaw. He said that he was very worried by the suddenness of her condition and he took his child immediately to an expensive medical practitioner in Mataram (the capital city of Lombok) who recommended expensive medicines to treat the condition. The affliction worsened and the medicine did not help in any way, so Bado went to his mother and then to the local Hadji to ask his advice. Both recommended that he should take his daughter to the belian in his village. This he did. The belian diagnosed the child’s condition as ketemuk arising from the fact that members of his wife’s family had neglected to care for their deceased grandfather’s grave. The belian emphasised that the spirit of the deceased grandfather (their daughter’s great grandfather) had become very angry and had inflicted this condition on the child as a punishment to the family.

The child’s parents were instructed to tend the grandfather’s grave giving expiatory prayers and offerings to their deceased ancestor because his spirit (or soul) had been offended by the lack of respect shown by close family members. They had not cared for him by ceremonially visiting his grave and giving him recognition through prayers and offerings of incense, rampe and food. One family member had continually failed to invite him back into his family home during Ramadan and to provide a ritual celebration (rowah) celebrating and respecting the deceased ancestor. When the family began to give ritual offerings at the grave site and prayers of reverence to the deceased relative the girl’s facial paralysis miraculously disappeared and she quickly recovered.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank my partner and fellow anthropologist Dr Barb Dobson who accompanied me in our fieldwork adventures in Lombok on different occasions between 1992 -1997 and who proof read the final version of this short paper. These photos were taken by Barb and myself together with extensive video footage of the traditional healing techniques practiced by male and female shamans and the traditional bone setters of Western and Central Lombok. I hope one day to upload some of this extraordinary video footage to our website.

ANNOTATIONS

- Ketemuk is defined as the ‘entry (of a spirit)’ (Sasak Dictionary 1995:188). Various translations provided by my Sasak-speaking informants included: Meeting a spirit and being touched by it. It causes sickness; ‘Being touched by a jinn, usually by accident, or damage to the property;’ ‘An iIlness resulting from meeting a ghost, jinn or Satan;’ ‘When you touch a jinn it sticks to you like a shadow and is with you wherever you go.’ My primary informant Bado told me that the victim accidentally or unwittingly comes into contact with the invisible agent from a parallel existence, for example by brushing against it or in a more extreme example by destroying the property or injuring a resident spirit (such as a jinn or bakeq). Bakeq is a Sasak term meaning a non-Muslim jin, satan or demon spirit.

It is difficult to avoid bumping into an ancestral spirit or soul (roh) as they were believed to return to their village at any time and to frequent the same places as their living descendants. Funerals were particularly dangerous, as were visitations to graveyards, especially during ceremonies on the last week of Ramadan when deceased souls were said to return in large numbers to visit their families. It was not the souls of one’s family that were most feared but the accidental meeting of someone else’s deceased kin. It is only through consultation with a belian who specialises in this kind of spirit-induced sickness that the specific cause of the sickness can be determined and the offended spirit can be placated. - The ritualized presentation of andang-andang to the belian is performed prior to treatment. It traditionally consisted of the ingredients of betel quid and/or a quantity of rice (about a kilo), white string and/or a few old Chinese brass coins.

Traditionally illness in Lombok was viewed as the result of some supernatural or black magical agent invading the human body. Once the invading spirit had taken up residence in or on the victim’s body, it would feed on the bodily fluids, literally draining the sap from the body. The only means to extricate this invading spirit was to entice it out by deception using symbolic bait, a powerful jampi (spell) and strong massage strokes culminating in the rituals of pertuk and sembeq. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the most commonly used bait was the mildly sedative betel chew which formed an integral part of the andang- andang (the medicinal substances presented to a belian by the patient prior to treatment). - I have been told that when a betel nut quid was chewed by a traditional Sasak shaman as part of a ketemuk healing ritual, that the masticated substance became a homeopathic metaphor for the human body. The betel leaf represents the skin and veins, slaked lime (apu) the bone, betel nut the flesh and the red juice symbolises the blood.

When combined with a potent jampi (spell) inter-mixed with the saliva of the shaman, this substance becomes a potent bait that is believed to lure the invading spirit out of the possessed victim’s body. After the belian has chewed the betel mixture for a period of time, he takes the contents from his mouth and places it lightly on the victim’s forehead. The practitioner then subvocalises a jampi while focusing his attention on the invading agent. He then takes the betel residue (bait) from the victim’s forehead and throws it away. This act demonstrates to the patient and his or her family members present that the invading spirit has been removed. As a logical consequence to this performance the patient who is a believer in the shaman’s magical powers must necessarily recover. On such occasions the practitioner is aware of the particular ketemuk (jinns) and is generally confident that there is no need to diagnose the cause of the illness. - Traditionally when a person was infected by a jinn the initial treatment consisted of popot, jampi, pertuk and sembeq. The victim was then bathed in salty water to make sure that the jinn detached itself from the victim’s body. It was generally accepted that jinns had an aversion to salt. Sometimes salt was sprinkled in public places to get rid of jinns that were deemed to be a nuisance. For some unknown reason the salt water treatment was discontinued and is no longer used today.

- Sembeq – This is a commonly used treatment for certain conditions involving spirit possession known as ketemuk and some minor forms of black magic. The treatment traditionally involves a betel nut preparation as both a curative and diagnostic tool. Shamans today have little or no knowledge of the magical symbolism of the preparation and they simply regard it as sarat or custom. In traditional times the blood from a sacrificed animal was used as a sembek (protective medicine) especially during times of community crisis involving a contagious disease. In recent times garlic has been used as a sembeq to protect young people, especially children afflicted by jinns. It is believed by many that jinns have an aversion to acrid smelling substances (Informant Amaq Jamali, 1996, Western Lombok)

- This is a form of homeopathic magic which attracts ‘like to like.’