‘Calling up the Tuselak’: A ghost-hunting experience in Western Lombok

OVERVIEW

This narrative is based on my field notes and experiences in Western Lombok in July 1996. I would like to thank my partner and fellow anthropologist Dr Barb Dobson who accompanied me in our fieldwork adventures in Western, Central and Northern Lombok between 1992 -1997 and who helped to format the final version of this story

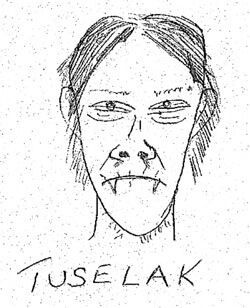

In Western Lombok the tuselak is an everyday part of village folklore. The modern day tuselak closely resembles the leyak of Bali – a blend of the traditional shape-shifting cannibalistic witch, fiendish sorcerer and gruesome Hollywood vampire. According to my local shaman informant Amaq Bahar, an expert on all things mysterious, tuselak mostly look like humans: they can be male or female, they are usually old, some are very ancient and the oldest ones are by far the most dangerous. They are unmistakable from their gaunt appearance, ashen-coloured face, long matted dirty white hair, weeping vacant eyes and an all-pervading stench of decay emanating from their cadaverous bodies. Not all tuselak manifest themselves in a human form: they have the ability to metamorphose into almost any animal or bird, such as a dog, monkey or chicken to enable them to beguile their chosen victims. Some village rumours even claim that tuselak can transmute into cars and motorbikes.

Witches and tukang sehere (sorcerers) are said to be close affiliates of the tuselak and in some villages are even reputed to be the tuselak. My Sasak informant Bado informed me in a figurative way that ‘the tukang seher and the tuselak are so close that they are like a light globe to a socket: they have to be connected to give light.’ It is said that tuselak never die and that their (evil) spirit is passed down through particular families from one generation to the next. The chosen descendant will inherit the tuselak spirit from the dying breath of the host and perpetuate the family line. From the time the spirit enters the body of its new host it takes mastery over mind and matter, giving birth to a fiendish persona with a voracious lust for human blood and viscera.

There exist other means by which a tuselak can transmit its evil knowledge and traditions into the psyche of unsuspecting villagers. It is said that sometimes villagers are seduced into ilmu tuselak without realising their fate by ruthless sorcerers who take advantage of their susceptibility and naivety. Once consumed by the evil power of ilmu tuselak, they are doomed to an uncontrollable life of wickedness and depravity.

One warm humid evening my assistant Bado came to our cottage while we were drinking tea and asked me if I was interested in attending a ceremony where a friend of his was going to ‘call up a tuselak’. According to Bado, this friend from a neighbouring village by the name of Rudi had somehow learned a ritual to ‘call up tuselak’ but the event was not to take place until midnight. We were expected to arrive at the prescribed location some hours before so as not to disturb the tuselak.

I asked Bado where the event was to take place. He replied that it was outside his village in a rice field (sawa) close to a small river on the edge of a forest. I enquired if there were any problems in filming the event. He said ‘No problems.’ My final question was ‘how much is this going to cost me?’ He looked at me and smiled hesitantly and said ‘if we see a tuselak, it’s up to you how much you pay.’

Soon after dinner we hired a vehicle and driver and set off to a rice field far away. The young men who accompanied us – Bado, Musta, Rudi and Ahmed (the driver) – were all excited and very talkative. ‘Mr Ken, Mr Ken,’ said Bado. ‘Rudi told me that it was his mother’s brother who taught him the ilmu tuselak. He’s famous for calling up tuselak in his village. He’s so famous that some people think he’s a tukang seher (male witch).’

Listening to these young men talking, I had the feeling that they would not have considered going out this late at night to a deserted rice field to ‘call up’ a tuselak unless Barb and myself were there to protect them. After several hours driving along dirt tracks taking wrong turns and generally going around in circles, we arrived at our rice field. It was cool, damp and somewhat foggy, the sort of place where one could imagine that tuselak might hang out. Our guides were all very nervous as they shone their torches in all directions while making as much noise as possible to scare away the jinns, demons and other supernatural agents that might be concealed in the fog. We walked precariously through a number of dried out rice fields until we finally arrived at our destination near a river on the edge of a heavily wooded hillside. The place had an eerie atmosphere about it. After waiting for some time, and wondering what to expect, we heard a distant cacophony of feral cat cries that were interrupted by a range of frog choruses. ‘Listen to those cats,’ I said to Barb. Bado interjected saying

‘No, no, Mr Ken, they’re not cats, they’re tujuls (the young children of tuselak). This place is evil and you must be careful of the jinns, bakek and tuselak. Murderers and thieves hide in these dark places by the river, especially down by the bridge.’

Bado pointed into the darkness. He said a quick bismullah (prayers to Allah) while perspiring profusely with fear in the cold, dank atmosphere of this lonely remote rice field.

Musta, the village masseur, who was the eldest of the young men present, looked at me nervously as he announced that no evil spirit would dare touch him because of his sabuk (protective belt, talisman). He lifted his shirt and around his protruding abdomen was a white plaited string to which was attached a number of tubular lead scrolls, not unlike fishing sinkers. He opened one of the scrolls and inside was an Arabic script etched in the lead. He assured me that these sacred Koranic texts would protect him from all manner of evil spirits. He also said that women were not permitted to see or touch his sabuk for fear that it would lose its power.

Being the inquiring anthropologist, I asked him if this was part of Sasak custom not to allow women to view sacred talisman? ‘No’ he replied awkwardly. It was only his belief based on what the crafty old Hajji who sold it to him had said. That his particular sabuk was made for only men to wear. ‘Anyway,’ Musta declared, ‘if women were allowed to wear it, my wife would want to wear it all the time and I would be left unprotected from all the evil that surrounds us.’ Despite Musta assuring me of his faith in his sabuk, he still seemed anxious and stayed close to us throughout the evening. We sat in the darkness on a dyke on the edge of the paddy field for the best part of an hour waiting for something to happen. I asked Bado ‘Why are we waiting so long?’ He looked at his watch, paused for a moment, and said concernedly – ‘It is too early! Tuselak don’t come out till around midnight.’ I accepted his explanation in good faith and settled back for another one and a half hours of waiting – until the bewitching hour. To pass the time away Musta related a story about his encounter with a tuselak on a dark moonless night. He said:

‘It happened while I was returning home to my village after being called out to treat a client in the nearby town of Ampernan. As I walked home exhausted, I was about to cross over a small bridge, when an elderly man, dressed in rags, appeared out of nowhere. I thought to myself, beggars are usually asleep by this time of night. I felt nervous. I began to walk faster over the bridge and as I passed him, he spoke in a shrill shaky voice. I could not help looking deep into his waxen face. It was pure evil and his eyes were streaming with tears. I will never forget those bloodshot, insensate eyes, as long as I live.’

‘My legs began to tremble and my blood ran cold. I started to run. It was then that I could smell the dank odour of rotting vegetation. I knew at that moment it was a tuselak! I began to run faster and faster, fearing my legs may become paralysed by the power of this evil creature. I looked once briefly over my shoulder and saw the tuselak following close behind. I ran faster and faster, my lungs bursting for air. I said a quick Bismullah to Allah and kept running for my life. Then when I reached home I locked the door, still trembling with fear. I was safe at last. I must admit if it hadn’t been for the holy inscriptions on my sabuk, I would be dead.’

Bado, who had been listening intently and was not to be outdone by Musta’s spine chilling tale, started to recount an anecdote that a friend from a neighbouring village had told him. The story was about a normal family who had lost their baby to a blood-sucking vampire, somewhat akin to a tuselak. While the family slept, this creature had entered the house and induced the mother who was sleeping with the infant into a deep state of paralysis (kededepan). It then proceeded to ravenously drain the infant of every drop of its life-giving blood. When the father awoke the next morning, he found his wife unable to move or speak, lying beside their lifeless child. There was a trail of blood leading to the doorway. By this time the hairs on the back of my neck were beginning to stand on end and I was reminded of my youth when I used to swap ghost stories with friends around a campfire at night.

It was at this time that I decided to stretch my legs. As I stood up and moved away I tripped on my untied shoelace, lost my balance and ended up going head over heels down a steep embankment on the edge of the paddy field. The next thing I remembered was landing hard on my right side, with a wrenching pain in my recently acquired (only 6 month old) prosthesis hip. I could hear Bado yelling, ‘Ee, ee, Mr Ken, Mr Ken, are you alright?’ There was a look of horror on the faces of my rescuers as they hauled me to my feet. The only thing that I was conscious of at that moment was a throbbing pain in my right hip. ‘God’ I exclaimed ‘I hope it’s not dislocated!’ My discomfort was the last thing on the minds of my assistants. They were engrossed in a serious debate about what had caused my fall. Was it a jinn, bakeq or a cunning tuselak?

Bado proclaimed his position, as my head assistant, and announced that the group was convinced that I did not fall from the embankment but was pushed by a bakeq (a malicious non-Moslem jinn). He declared: ‘there are many primitive jinns here – this is jinn country. We shouldn’t be here, it’s a dangerous place.’ Musta, out of the blue, startled the others by announcing that he had seen a large white dog running past him, only minutes before I had fallen. There was an anxious silence before Bado explained nervously that it was probably not a jinn that pushed me but rather a tuselak. He said that they often disguise themselves as dogs, chickens and even snakes to get close to their victims. ‘They are very cunning, therefore, we must be vigilant at all times this night.’

No matter what I said to my assistants I could not convince them that my fall was accidental, simply the consequence of tripping over my untied shoelace. As they continued to debate between themselves as to the identity of the supernatural being that had pushed me over the embankment, I asked Musta if he could massage my hip to relieve some of the pain. He did so reluctantly and with great caution, apparently worried that some malicious agent may still be in possession of my body. Within minutes of his massage my pain began to subside and everything became eerily silent. We were alone with Musta. The others had disappeared into the darkness. I asked Musta where had the others gone. He looked bewildered and said ‘I don’t know.’ He sat there thinking for a while and then announced that they had gone to the village to get some firewood. ‘Firewood’ I exclaimed in surprise. ‘Didn’t they bring any firewood with them?’ ‘Maybe they did’ Musta replied sheepishly ‘but that wood was wet and you can’t light a fire with wet wood!’ It seemed that this was the only explanation that I was going to get so I discontinued my questions.

We sat waiting for another hour until we heard the others coming back. They were now making as much noise as they could, as if to awaken the dead. ‘They are making sure that the jinns will hear them and get out of their way,’ said Musta. As they came towards us, Bado’s torchlight shone ghostly amid the foggy atmosphere of the rice field. When Bado appeared out of the darkness he was wearing a pair of military trousers with a jungle camouflage design. All of the young men had removed their shirts. When I asked why they had removed their shirts, Bado replied authoritatively that ‘the tuselak cannot see you if you are not wearing a shirt.’ I thought to myself was this because their skins were dark-coloured and blended into the darkness or was there some other hidden mysterious reason? I asked Bado, why the tuselak cannot see a person without a shirt. He shrugged his shoulders and said ‘They just can’t’, its sarat.’ This was a common answer to many of my probing questions when asking for explanations of traditional rituals and folk legends. Sarat simply means a necessary condition or requisite dictated by custom.

At this point Rudi arrived ready to start his ritual. He carried with him two large white bowls that he had borrowed from his mother’s kitchen. In one bowl there were six crabs. However, one of the crabs had died and Rudi became anxious that the ritual might not work with only five live crabs instead of six. He explained that tuselak are attracted to live crabs. It’s their favourite food and they would be used to entice the tuselak to this place. In the other bowl was some water infused with the petals of twelve different flowers. This water is called rampeh and is used as an offering to a variety of spirits.

Rudi carries the crabs and rampe the favourite foods of the tuselak in preparation for the ‘calling up’ ritual (Photo by Barb Dobson)

Rudi walked about twenty metres to the edge of the rice field close to the start of the jungle. He squatted down and lit four sticks of sweet-smelling incense that he placed in the ground in front of him. He then positioned the rampeh on his left side and the crabs on his right. He started to construct a small fire with wood and paper. When he had finished this task, he clapped his hands several times and then began to chant. He took out a box of matches from inside his sarong and ignited the paper. A warm glow started to appear, reflecting in the foggy atmosphere.

Everyone sat watching in anticipation, waiting for the tuselak to appear. The fire died down very quickly leaving a smoky smell of burning vegetation and incense. Bado explained ‘that is the smell of the tuselak.’ No one commented. We could see Rudi in the distance striking matches and trying desperately to relight the fire. He was still chanting. I asked Bado what the tuselak would look like when it appeared. ‘Oh,’ he said ‘it will look like a ghostly blue shadow hovering over the fire and then it will disappear into the darkness. It may look like a person or a dog or whatever form the tuselak chooses to become.’

We sat watching Rudi striking matches for at least another ten minutes. He finally succeeded in kindling a small fire that lasted only a few brief moments before extinguishing itself. Rudi stopped chanting, stood up and walked despondently towards us. He announced that the tuselak was too frightened to appear because there were too many people present. He explained that tuselak are shy and will not materialise if they sense any danger and Bado reiterated that tuselak get frightened if there are too many people. He looked relieved that it was all over. Rudi finally remarked that tuselak were afraid of foreigners because tuselak only understand Bahasa Sasak – they don’t speak English.

We walked back to the car in silence feeling disappointed that the tuselak had not materialised. As we drove back to our cottage Musta whispered that the others were wrong. The tuselak had appeared, he believed, in the form of a white dog. When the dog had passed him, it had sensed the shielding power of his sabuk and was afraid to linger. I am sure that if Rudi had brought with him dry firewood and had positioned his fire in a damp location with decaying vegetation, we may have all witnessed the apparition of a tuselak. This is because the heat from the fire would have released an ignited methane gas that would have formed an amorphous blueish light over the fire and once ignited may have hovered in the fog over the cool surface of the rice field, producing the silhouette of a tuselak-like apparition. I was very interested in the comment that a tuselak smells like decaying vegetation and that tuselak were always observed late at night hovering over drying rice fields. Could it be that methane gas alone was (and to this day still is) responsible for the perceived materialisation of tuselak and other ghostly apparitions that appear late at night and form such a rich and important part of traditional and contemporary folklore, not only in Indonesia but in other parts of the world as well?

Annotations

- The tuselak of Lombok is a regional version of the vampire-witch manifestation found in certain Southeast Asian traditions including, for example, the leyak of Bali and the aswang of the Philippines.

- Barb told me that when she was carrying out anthropological fieldwork in the Philippines between 1979-1982 her informants often answered questions with kauggalian translating as ‘tradition’ or ‘custom,’ this being the Tagalog language equivalent of sarat.