Betanggeq: Arabic influence in Western Lombok folk medicine

Prepared by Ken Macintyre based on field observations in Western Lombok in 1996

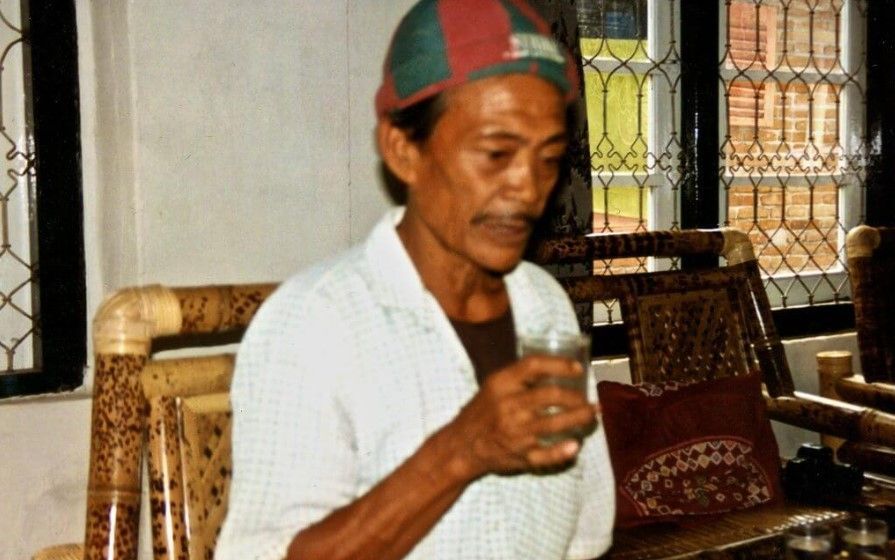

In 1996 while researching healing practices in Western Lombok, I had the good fortune to meet one of the last remaining Belian Daraq (blood physicians) who practiced a form of wet cupping (blood letting) using a buffalo horn or tanggeq. This technique was known as betanggeq.

Tools of the trade include a buffalo horn (tanggeq) (pictured above), candle wax, sharp knife (pemaja), skewer (penusuk) and a coconut shell bowl (jegai).

Betanggeq is not a traditional Sasak medical technique but was introduced by Arab traders from the Middle East where it is called hijama – a form of “wet cupping” where blood is drawn from a patient by means of sucking using a horn. The term hijama literally means ‘sucking.’ My informant Pak Udin had no idea that his profession had originated in the Middle East. All he was aware of was that the ilmu (knowledge) had been passed down to him through generations of senior male members of his family.

Folk medical uses of Betanggeq

Betanggeq follows the humoral theory of hot and cold imbalance and tries to restore balance by removing blockages of cold stagnant blood that are perceived to be the cause of a range of ailments located in different parts of the body. According to Pak Udin, treatments on the lower back relieve rheumatic conditions, lumbago, sciatica and muscular lower back pain whereas betanggeq on the upper back and neck region are believed to relieve neck and shoulder pain, headaches (pinyeng), dizziness insomnia, weak heart and ulcers (budun).

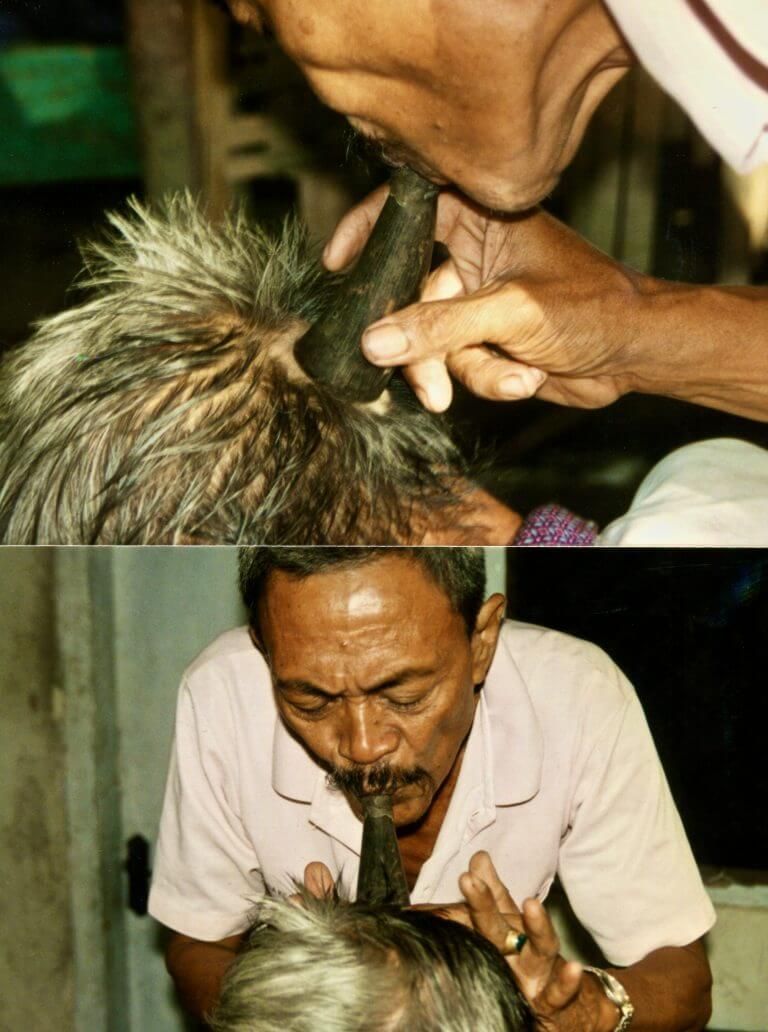

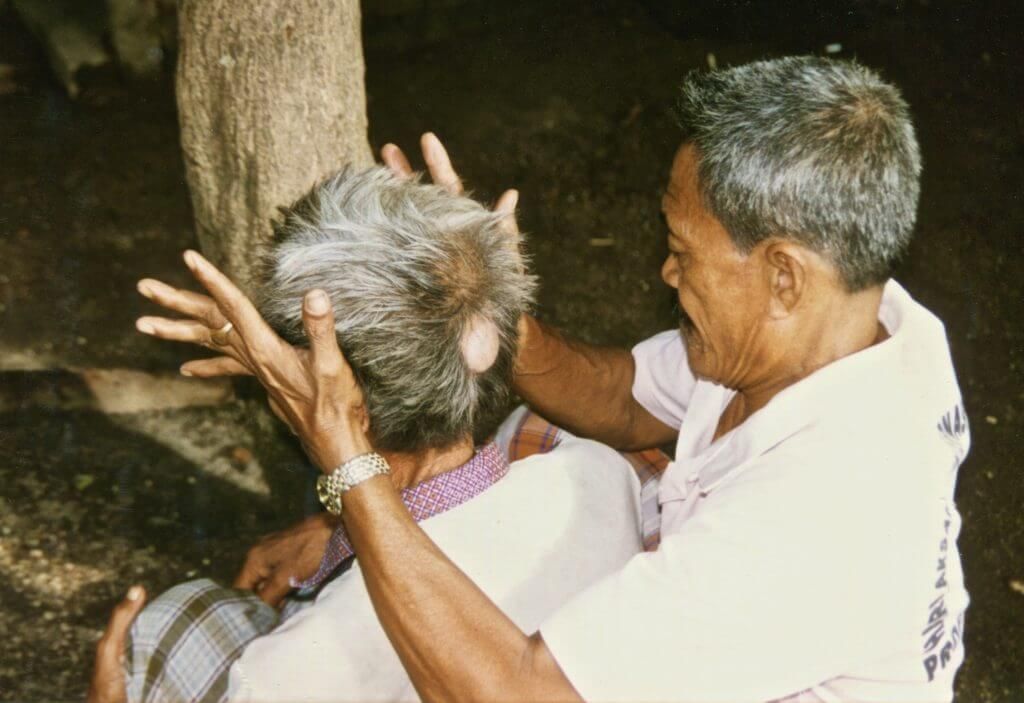

The man pictured above visits Pak Udin every six months for betanggeq treatment to relieve his chronic headaches and insomnia. He finds it a very effective therapy.

STEP 1: Pak Udin starts his treatment by offering his client a drink made from a hot water and ginger drink known as aik-jahe (ginger root, Zingibar officinale). He whispers his jampi (spell) into the hot drink and offers it to his client. In traditional Sasak medicine jahe (ginger) is believed to be one of the hottest and potent medicines for alleviating conditions believed to be caused by ‘cold blood.’

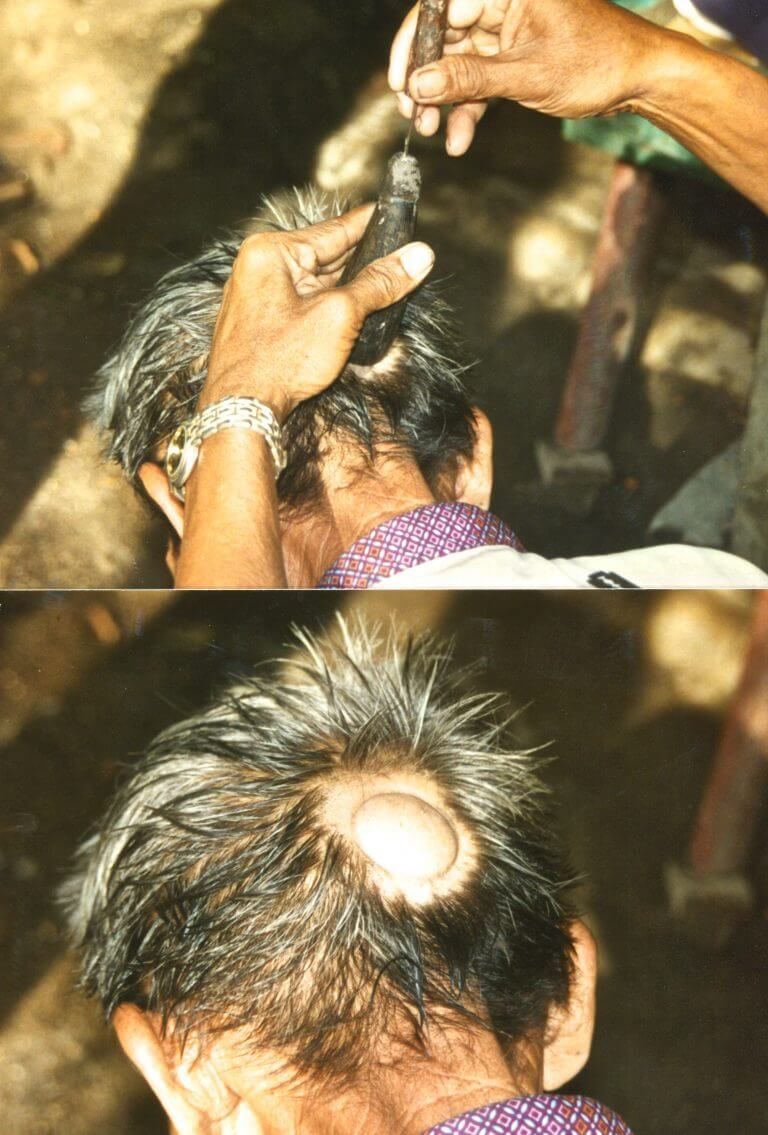

STEP 2: The hair from back of the head is shaved using a small sharp knife known as a pemaja. Note the shaven area is close to the side where the client experiences his head pain.

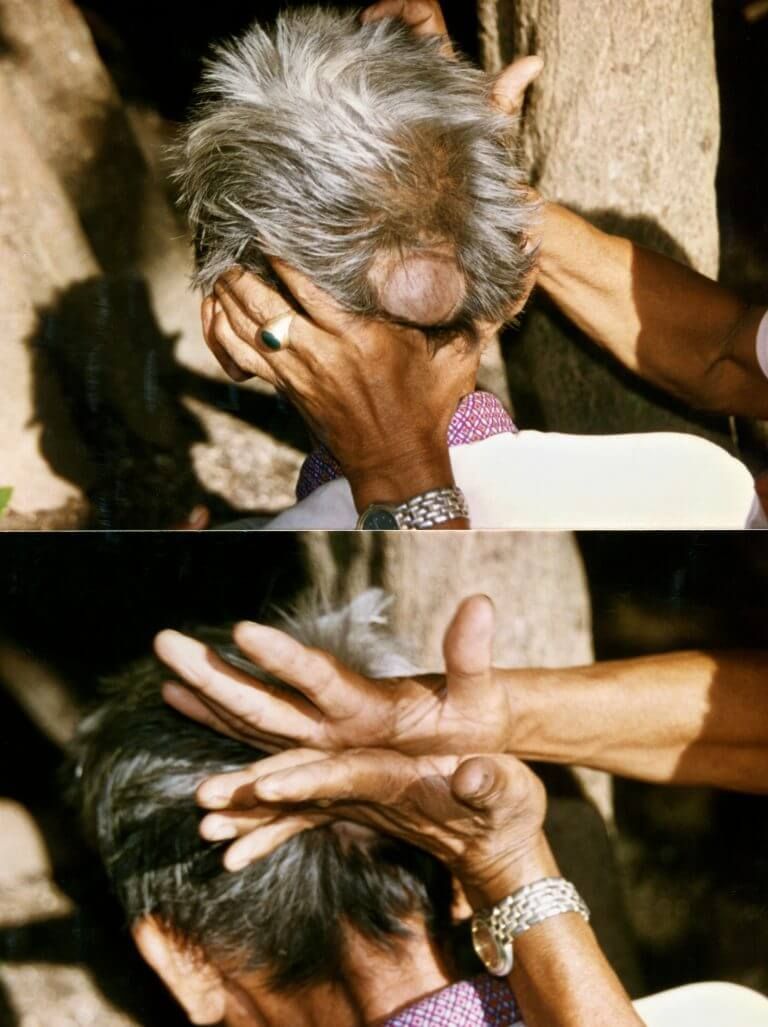

STEP 3 Pak Udin performs popot – a deep penetrating massage to the head, neck and shoulders that relaxes his client, stimulates circulation and makes him responsive to the positive suggestions of the healer. Based on my observations over a number of years popot would appear to be an integral part of traditional Sasak medicine.

STEP 4: A buffalo horn is carefully centred over the newly shaved area. Pak Udin sucks (isep) deeply at the end of the horn removing the air from within, creating a strong vacuum on the skin. He plugs the end of the horn with candle-wax to seal it.

STEP 5: After fifteen minutes the seal is released using a skewer (penusuk) and the horn is then removed to reveal a raised circular swelling.

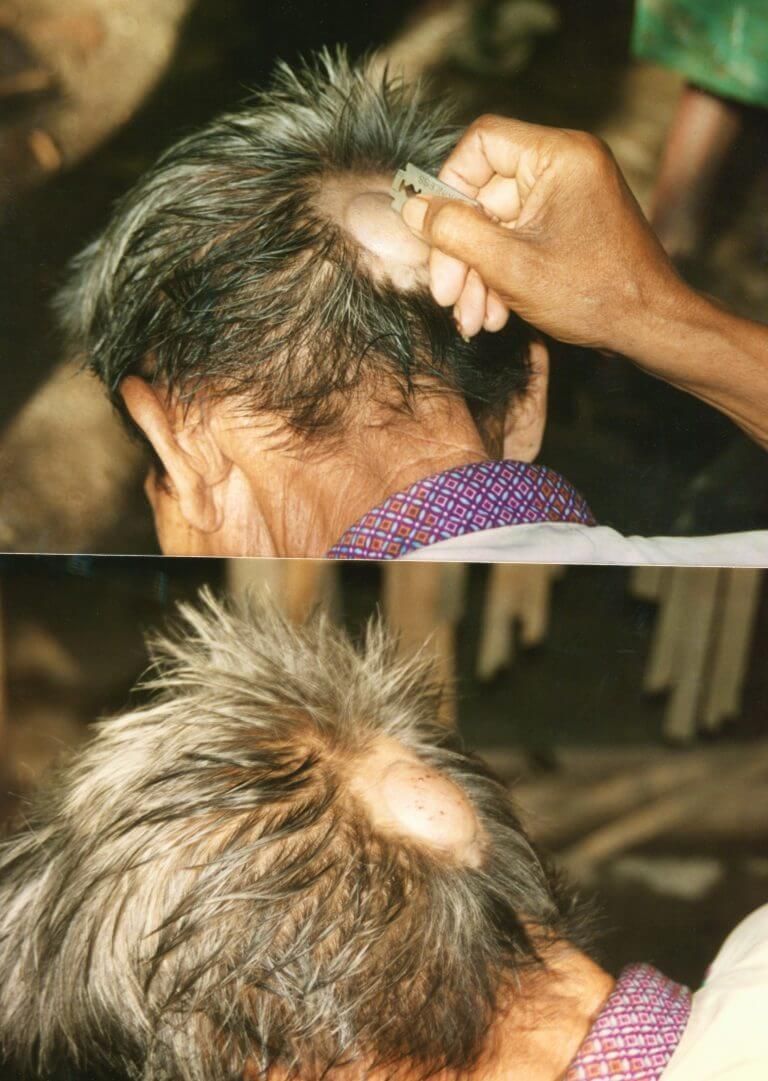

STEP 6: The raised area is lightly scarified using a razor blade.

STEP 7: Pak Udin reapplies the horn over the scarified area and sucks it, once again, creating a strong vacuum on the skin.

STEP 8: After fifteen minutes Pak Udin pierces the wax seal on the horn.

STEP 9: Pak Udin lifts the horn to expose a glob of darkish blood which he removes using the edge of the horn to scrape the blood into a coconut shell container (jejai). He then shows his client the blood that he has removed and reassures his client that everything will be fine.

STEP 10: Pak Udin wipes the swelling with a dry cloth to remove the remaining blood.

STEP 11: At the conclusion of the treatment Pak Udin vigorously massages his client’s head using a type of popot to stimulate the circulation and to ensure there are no further blockages.

STEP 12: Pak Udin performing the final strokes of the head massage (popot).

Many of the traditional healers we interviewed when conducting our research at the village level were illiterate farmers, artisans and labourers who practiced their healing skills on a part-time basis. They had usually mastered their healing skills through observation and long term apprenticeship to senior family members who over time impart to them the ilmu or knowledge of their specific healing techniques, both verbally and by demonstration. It was impossible for us to ascertain the origins and cultural theories behind these practices because whenever we asked questions as to how and why they were practised, the response was invariably “sarat” meaning it has always been this way.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

All photos in this paper were taken by Ken Macintyre in 1996.