Ochre: an ancient health-giving cosmetic

Prepared by Ken Macintyre and Barb Dobson

Research anthropologists

‘Both sexes smear their faces and the upper part of the body with red pigment (paloil), mixed with grease, which gives them a disagreeable odour. This they do, as they say, for the purpose of keeping themselves clean, and as a defence from the sun or rain. Their hair is frequently matted with the same pigment. When fresh painted, they are all over of a brickdust colour, which gives them a most singular appearance.’ (Nind 1831: 25)1

It seemed paradoxical to the early white settlers of this country, as it still does for many of us today, that by applying a coating of grease mixed with a red clay pigment containing iron oxide (ochre) could be an effective means of maintaining healthy skin and bodily hygiene. Traditionally the Noongar people of southwestern Australia inhabited an environment where fresh water was a scarce resource during a large portion of the year and in order to maintain bodily cleanliness they devised an effective substitute for water. This was a topical unguent known as wilgi made from a mixture of ochre (iron oxide) and animal fat. Ochre is an earthy pigment containing ferric oxide, typically with clay, which varies in colour from dark red to brown to yellow.

In Noongar culture wilgi (or wilgie, wilghee) as a bodily emollient was used for many different purposes including as a skin protectant shielding the body from the adverse effects of the sun’s ultraviolet rays. The photo-protective properties of red ochre have been confirmed by recent experiments conducted by an international team of scientists.2 The dense greasy covering of wilgi provided insulation during the cold, wet and windy seasons, while during the heat of summer it functioned as a humectant reducing moisture loss from the skin. Wilgi may be likened to a protective layer of clothing.

The skin is as soft as the finest velvet. This is probably caused to some extent by the use of wilghee – an unguent composed of red-ochre and grease – with which they anoint themselves. A supply of wilghee is generally carried by the women in their bags for the use of the party that they encamp in the evening. They then rub it over their faces and often over the whole body as they sit round their fires.’ (Philip Chauncy in Brough Smyth 1878: 238)

Philip Chauncy, assistant government surveyor at the Swan River colony in the 1840’s, describes the detrimental consequences to his Noongar friend Weeban’s skin after he had been prevented from wearing wilghee during his period of imprisonment at Rottnest Island. Chauncy writes:

‘The colour of the skin was a sort of iron-grey unlike natives I have seen. This was because he had not been allowed any grease to anoint himself with in accordance with the custom of both men and women.’ (Chauncy in Brough Smyth 1878: 276).

A number of Aboriginal prisoners died at Rottnest as a result of heatstroke and exposure to the cold, having been prevented by prison authorities from using ochre and grease to protect themselves.

Wilgi as a protection against insects

Wilgi provided an effective barrier against the ravages of biting insects, such as mosquitos, fleas and ticks. This was observed by a number of early recorders, including George Fletcher Moore who suggests that the custom of applying ochre to the skin has its

‘origin in the desire to protect the skin from the attacks of insects, and as a defence against the heat of the sun in summer, and the cold in the winter season. But no aboriginal Australian considers himself properly attired unless well clothed with grease and wilgi.’ (Moore 1842: 76).

Moore, after his first ten years residing in the Swan River colony, became aware of the different uses of wilgi by Noongar people including as a protective barrier against the harsh climate and environment of southwestern Australia. It is well established in the scientific literature that mosquitos are attracted by odours emitted by humans such as carbon dioxide and perspiration. Noongar people found that wilgi provided them with a protective shield that concealed bodily odours. Smoke from campfires permeated the fatty covering of the wilgi smear, further masking the human scent. The ability of wilgi to mask the human scent was advantageous for hunters while stalking large game, such as kangaroo and emu.

Ochre as an ancient cosmetic and bodily adornment

Red ochre was prepared by burning the hard clay and rocky material to obtain the iron oxide pigment which was then ground up into a fine powder that readily mixed with animal fat. A number of early recorders, such as Bunbury (1836), Grey (1840), Austin (1841) and Moore (1842), describe how it was used as an adornment.

Bunbury (1836 in Cameron and Barnes 2014: 166) describes how

‘This ‘wilghi’ which is a preparation of red earth & grease constitutes their favourite ornament & covering, when smeared with this they consider themselves particularly handsome…’

He further notes that the men adorned their heads with cockatoo feathers – sometimes white, sometimes black with red stripes

‘or at other times reddish brown when saturated with wilghi. These are worn on the head or as armlets & occasionally when plentiful in the belt: well adorned with these & smeared with grease & red ochre a warrior is fully dressed….’ (Bunbury 1836 in Cameron and Barnes 2014: 168).

Grey (1840), Moore (1842) and Austin (in Roth 1902) also highlight the the use of wilgi as a cosmetic:

‘wil-gey – burnt ochreous clay with which the natives paint themselves (1840: 128).

‘wilgi – An ochrish clay, which when burned in the fire, turns to a bright brick-dust colour. With this, either in a dry powdery state, or saturated with grease, the aborigines, both men and women, are fond of rubbing themselves over. The females are contented with smearing their hands and faces, but the men apply it indiscriminately to all parts of the body. Occasionally they paint the legs and thighs with it in a dry state, either uniformly or in transverse bands and stripes, giving the appearance of red or parti-coloured pantaloons. This custom has had its origin in the desire to protect the skin from the attacks of insects, and as a defence against the heat of the sun in summer, and the cold in the winter season. But no aboriginal Australian considers himself properly attired unless well clothed with grease and wilgi.’ (Moore 1842: 76).

‘The grease‑paint, in addition to serving a decorative purpose, was useful in keeping away the ants, sandflies, and other insects. The renewal of the painting process depended greatly upon the supply of the ochre itself, and whether for the purpose of paying a visit to another camp, they were desirous of appearing at their best. It was not done every day, but if they were young men and fancied themselves, they would renew it as often as the inclination took them.’ (Austin 1841: 31-32).

‘The red ochre, wil‑gi, was rubbed up in the hand dry, or pounded with a stone to a fine powder.’

Austin (1841 in Roth 1903) further describes how the ochre was mixed with animal fat and smeared over all parts of the body including the head and hair

‘until the skin showed a uniform appearance of a greasy vermillion colour.’

James Brown (1856: 12), referring to the King George Sound region, describes how red ochre and grease was used as a hair adornment:

‘plastering his uncut hair with a thick cement made of red ochre and grease. A diversity of style is adopted in its dressing; some have the head covered with quantities of small and shining red-ringlets, some have it bound around with cord, and then covered with a solid mass of stiff and clay-like pomatum….’

Use of ochre as a medicine

Throughout the anthropological literature there has been much emphasis placed on the ceremonial and decorative use of ochre in Noongar culture but there has been little mention of its use as a medicine. Nind (1831:42) provides the earliest references to its application in the treatment of spear wounds. He observes:

‘They are very skilful in extracting the weapon, after which they apply a little dust [ochre], similar to what is used for pigment, and then bind the wound up tightly with soft bark [paper bark].’ (Nind 1831: 42)

Red ochre is a very effective drying agent for wounds. In Noongar culture it was either sprinkled on dry or mixed with water or saliva in the mouth or sprayed onto the wound. Ochre was mixed with emu or goanna fat to make an ointment similar in many ways to zinc ointment and was used to treat wounds and a range of skin conditions. The substance according to Aboriginal anecdotal accounts is reputedly an effective agent for drying suppurating wounds, ulcers and boils. In the Eastern Goldfields in the 1970’s informants described how ochre was ground up, mixed into a fine powder, blended with goanna or emu fat and applied in the treatment of wounds, insect bites, muscle sprains and general aches and pains associated with arthritis. This was also the practice of Noongar people according to a spokesperson from the Moora area:

‘The “old people” used ochre and fat as a remedy for everything.’ (William Warrell, 1999 personal com.)

He also stated said that in the “old days” small pellets of ochre were ingested as a treatment for lethargy and fatigue. He called these “the Noongar iron tablets.” Bunbury (1836: 165) provides evidence that traditional people used iron-rich water possibly as a tonic. He describes the Noongar people drinking water from ‘a small swamp of red ochrous or irony earth” and comments:

‘the Natives drink the water willingly not withstanding its strong irony taste & I have no doubt it is very wholesome.’

This reinforces the idea that Noongar people must have had a knowledge of the therapeutic use of iron supplements.

Studies conducted in Africa have demonstrated that ferruginous ochre pigment has antibacterial and antifungal properties making it effective in the management of infections associated with some pustular skin eruptions (Dauda et al. 2012: 5211).

Use of ochre in tanning kangaroo skin

The antifungal and antimicrobial properties of ochre together with its softening qualities and rich red colouring, according to Dauda (2012) renders it

ideal for tanning, softening and colouring leather (Audouin and Plisson, 1982; Wadley et al., 2004).’ (Dauda et al. 2012: 5210)

Nind (1831:25) records how Aborigines at King George Sound traditionally prepared the kangaroo skin cloak by rubbing ‘grease and a sort of red ochreous earth, which they also use to paint the body’ onto the hide. We would suggest that this rubbing of fat and wilgi onto the non-fur side of the kangaroo skin probably assisted in its preservation as well as providing a colourful tan to the mantle.*

Austin (1841) also refers to the use of wilgi in the colouring and tanning of the kangaroo-skin cloak:

‘They wore a cloak, bo‑ka, made of kangaroo hide (sometimes with a collar some 5 ins. or 6 ins. deep, which fell over) hanging to just below the knee, and shorter in front than behind. It was worn with the hairy side in, and was coloured on the outside with the wil‑gi.’ (Austin 1841 in Roth 1902: 32).

Chauncy (in Brough Smyth 1878:237) also refers to Noongar people smothering the outside (non-fur side) of the boka as well as their faces and bodies with wilghee. We would suggest that not only was this a means of decoration but that the ochre and fat helped to preserve and waterproof the hide. This practice of using ochre to tan animal hide probably dates back many thousands of years.

Ochre as a ritual and ceremonial decoration for tools

Ochre mixed with fat was often used to imbue artefacts with spiritual powers for hunting and ceremonial activities. Ochre also helped to condition and preserve the wood. Mountford (1976: 85) referring to Central Australia notes that when the sacred objects are taken out of their secret places, they are greased and rubbed with red ochre and held against their bodies or faces

‘because, they explained, it made them feel stronger.’

The Noongar also used ochres for artefact decoration and spiritual renewal. According to Bates (in White 1985: 276):

‘All spearthrowers are covered at one time or other with red ochre, and are often decorated with both red and white pipeclay and with birds’ down on special occasions.’

Ochre, rock art and symbolism

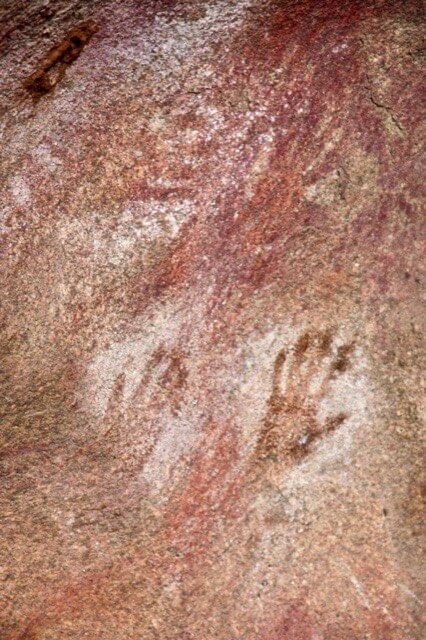

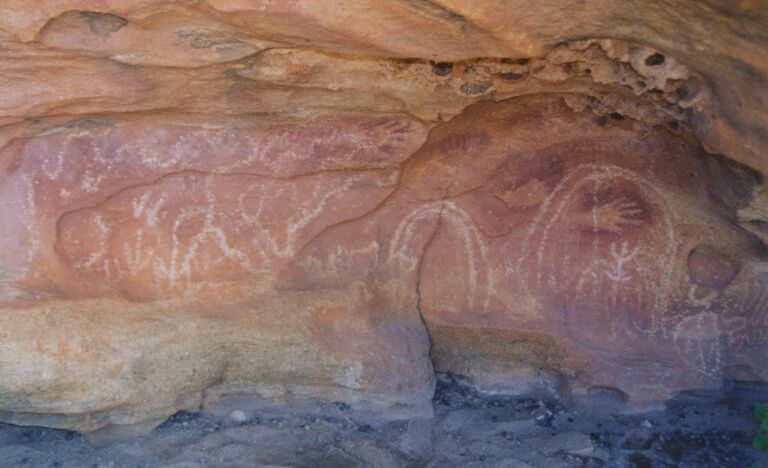

The earliest known paint used by humans was the natural red earth pigment ochre. It was used extensively throughout Aboriginal Australia on rock art and artefacts. The pigment was mixed either with blood, fat or saliva (or water), depending on the particular art form. The hand stencil art form, which is one of the earliest forms of rock art in Australia, often symbolised ownership of country. It was typically created by mixing ochre and water in the mouth and spraying it onto their splayed hand on the wall, leaving behind the outline of the hand.

Both Moore (1831) and Drummond (1840) describe a cave they visited in the Avon Valley, south of York, that was decorated in ochre with a mysterious circular motif together with a number of hand stencils:

‘… there was a rudely marked round figure which was supposed to represent the sun (but I do not know why) and in different places near this round figure were the impressions of open hands. It appeared as if the rock had been covered with some reddish pigment & these impressions formed by rubbing a stone against a rock like this…’ (Moore 1831 in Shoobert 2005: 260)

Drummond (1840) describes it as:

‘a curious cave, called by the Aborigines Coujargnording, or the moon’s house. This cave is remarkable for having imprinted in the solid rock in which it is formed, a circular figure about 18 inches in diameter, and several mysterious prints of the human hand…’ (Perth Gazette 12th December 1840).

This cave which is located in the side of a granite cliff south of York was first recorded by Dale (1830), hence it’s European name “Dale’s Cave.” It is also known as the Sun cave or Moon cave. Some other ochre-decorated caves within Noongar territory include Frieze Cave (south of York), Mulka’s Cave (north of Hyden), and Marbaleerup (northeast of Esperance).

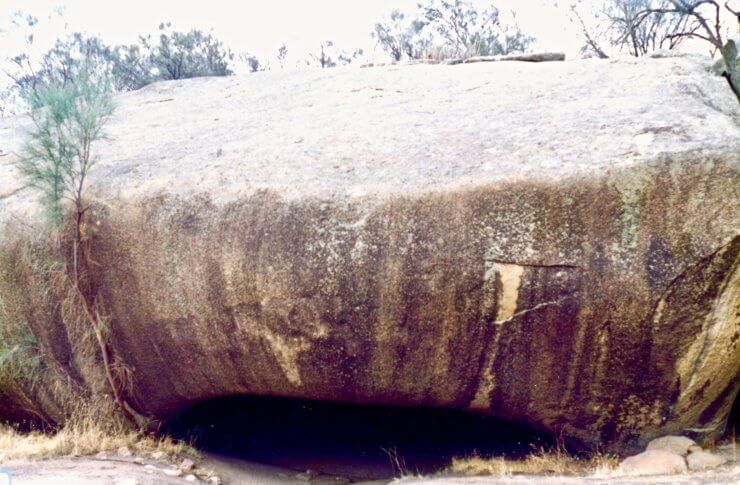

The hand stencils and motifs pictured below were observed by us on a granite rock shelter northeast of Cue, Western Australia.

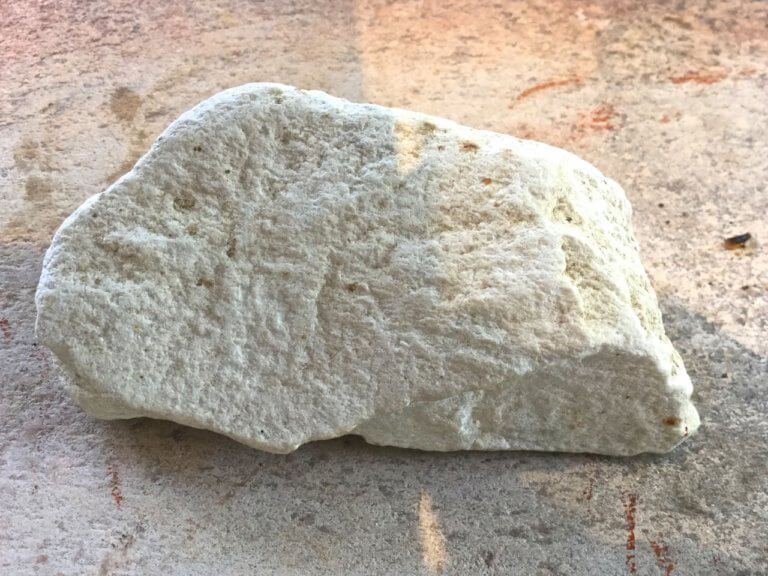

Other coloured ochres (and white clays) were also used for body decorations, ceremonial activities and rock art. Even though these substances are chemically different and traditionally had different names, they are colloquially known as “ochre.” There are ochre deposits recorded at Red Hill in the City of Swan, northeast of Perth. These ochre sites form part of a larger site complex in the Darling Scarp which includes the ancestral Owl stone, see https://anthropologyfromtheshed.com/project/report-owl-stone-aboriginal-site-red-hill-northeast-perth/According to anecdotal sources these red and white ochres may have been traded from this area. Archaeological evidence from Red Hill suggests that red ochre may have been processed and used on-site.

The ochre trade

Red ochre was an essential ingredient of traditional Aboriginal culture that was highly valued for its fine smooth texture and deep red colouring. Its place of origin often connected the user to the final resting place of a significant totem or ancestral being, such as the kangaroo, dingo or emu, where it symbolised the metamorphised blood of a particular ancestral being. Yellow ochre was often said to signify the fat or bile. Red ochre obtained from places of high spiritual significance, such as Wilgie Mia (literally wilgi, red ochre + mia, house, home, shelter) in the Weld Range in the Murchison, Western Australia (in Wajarri Yamatji country) was regarded as the potent blood of the ancestral kangaroo. The quest to obtain this sacred element may be likened to a pilgrimage-like expedition to the resting place of a totemic ancestor. Trade for such a precious resource was often conducted through an intricate network of song lines over considerable distances. There is anecdotal evidence to suggest that Noongar people from as far away as King George Sound and Esperance travelled to Wilgie Mia to obtain this precious substance.

Ochre was a trade item that was exchanged between groups during large social and ceremonial gatherings. The meetings where ritual exchanges took place were known by the Noongar as mandjar. Bates (in White 1985: 281) describes an ochre deposit in the Perth area as follows:

‘The Perth people had an ochre patch in the neighbourhood of Monger or Herdsman’s Lake, and this was a staple article of commerce, the Perth ochre going north…’

Bates in an undated paper further refers to Fanny Balbuk working for her father from a young age at the family’s ochre pit. She writes:

‘A specially fine greasy “pocket” lay in a swamp, which later became the site of Perth’s railway terminus. Some little firing process solidified and increased its greasiness, this being done by the Perth women…(Balbuk) prepared the wilgi for trade and her father sold it to the native groups …Gingin, Kellerberrin…(Balbuk) often carried the wilgi she had prepared from the wilgi-garup (wilgi-hole) to outlying places north and north-east of Perth.’ (Bates n.d.)

According to Bates (1929) Fanny Balbuk inherited the ochre pit from her father and she was the last owner before it was covered by the foundations of the Perth railway station.

Early archaeological evidence of ochre use in Aboriginal Australia

Archaeological evidence from southeastern Australia indicates that ochre was used in association with human burial many thousands of years ago. Paterson and Lampert (1985:1) state that:

‘… the earliest, and most spectacular, evidence for its use comes from the Lake Mungo site in western New South Wales where the body of a man who died some 30,000 years ago had been coated with red ochre at the time of burial (Bowler & Thorne, 1976: 129).’

The only documented use of ochre in funerary rites in southwestern Australia, that we could locate, was Austin’s reminiscence (told to Roth) that wilgi was used as a grave marker:

‘At burial, some offerings were left generally in the shape of damaged weapons, etc (but no food) on the grave itself, while upon the bark of neighbouring trees was smeared some red paint (wil‑gi), either in complete rings, or horizontally zigzag lines.’ (Roth 1902).

The extent to which wilgi was used in association with traditional Noongar funerary rites and ceremonies is unknown and to our knowledge has never been researched.

We would conclude that ochre was an essential ingredient of traditional indigenous culture providing a medium for bodily protection and decoration, art, ritual and medicine.

The Noongar people had no doubts about its efficacy in everyday use as the following quote by Philip Chauncy demonstrates:

‘Once, when travelling with a native guide, he saw that I was much inconvenienced by the great heat and the clouds of mosquitos and flies, and said – “What for white fellow all same fool? use um soap too much, instead of wilghee.” (Chauncy in Brough Smyth 1878: 238)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bates, D. 1929 ‘Aboriginal Perth.’ The Western Mail. July.

Bates, D. (n.d.) Native trade routes. Commerce of Australian Aborigines (Battye Library Reference PR 2573/24).

Bates, D. 1985. The Native Tribes of Western Australia. Isobel White (Ed.) Canberra: National Library of Australia.

Bates, Daisy 1992 Aboriginal Perth: Bibbulmun Biographies and Legends. Peter J. Bridge (Ed.) Carlisle, Perth: Hesperian Press.

Bindon, P. and Chadwick, R. (eds.) 1992 A Nyoongar Wordlist from the South-West of Western Australia. WA Museum, Anthropology Department.

Brough Smyth, R. B. 1878 The Aborigines of Victoria. 2 vols. Melbourne and London.

Browne, James 1836-1838 Aborigines of the King George Sound Region: the collected works of James Browne. Compiled and edited by anthropologists Ken Macintyre and Barbara Dobson. Victoria Park, Perth: Hesperian Press.

Cameron, J.M.R. and P. Barnes (eds.) 2014 Lieutenant Bunbury’s Australian Sojourn: the letters and journals of Lieutenant H.W. Bunbury, 21st Royal North British Fusiliers, 1834-1837. Victoria Park, WA: Hesperian Press.

Chauncy, Phillip 1878 ‘Notes and Anecdotes’ in R. Brough Smyth 1878 The Aborigines of Victoria. Vol 1. Melbourne and London.

Dauda, B.E.N., Jigam, A.A., Jimoh, T.O., Salihu,S.O. and A. Sanusi 2012 ‘Metal content determination and antimicrobial properties of ochre from North-central Nigeria.’ International Journal of Physical Sciences, Vol. 7 (31), pp. 5209-5212. Available online at https://academicjournals.org/journal/IJPS/article-full-text-pdf/C36A31716931

Dench, A. 1994 ‘Nyungar’ in Thieberger, N. and W. McGregor Macquarie Aboriginal Words. Macquarie University, N.S.W.

Drummond, J. 1840 ‘Report on the botanical productions of the country from York district to King George’s Sound.’ The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal. September 24.

Green, N. 1979 Nyungar – The People: Aboriginal customs in the southwest of Australia. Mt Lawley, North Perth: Creative Research Publishers.

Grey, G. 1840 A Vocabulary of the Dialects of Southwestern Australia. 2nd edition. London: T & W Boone.

Gunn, R. G. 2006 ‘Mulka’s Cave Aboriginal rock a site: its context and content.’ Records of the Western Australian Museum 23: 19-41.

Hallam. S. J. 1975 Fire and Hearth: a study of Aboriginal usage and European usurpation in south-western Australia. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Hassell, Ethel 1975 My Dusky Friends: Aboriginal life, customs and legends and glimpses of station life at Jarramungup in the 1880’s. East Fremantle: C.W. Hassell.

Moore, G.F. 1842 A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Language in Common Use Amongst the Aborigines of Western Australia. London: Orr.

Mountford, C. P. 1976 The Nomads of the Australian Desert. Sydney: Rigby Limited.

Nind, Scott 1831 Description of the Natives of King George’s Sound (Swan River Colony) and adjoining country. The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, Vol 1, pp. 21-51. Written by Mr Scott Nind, and communicated by R.Brown Esq. Read 14th February.

Paterson, N. and R.J. Lampert 1985 ‘A central Australian ochre mine.’ Records of the Australian Museum, 37 (1): 1-9. Sydney.

Roth, W.E. 1902 ‘Notes of savage life in the early days of West Australian settlement.’ Based on reminiscences collected from F. Robert Austin, Civil Engineer, late Assistant Surveyor, W.A. (1841). Paper read before the Royal Society of Queensland 8th March 1902. Draft copy of paper provided to us by Peter Bridge from Hesperian Press.

Salvado, R. 1851 in E.J. Storman 1977 The Salvado Memoirs. Nedlands: University of Western Australia Press.

Shoobert (ed.) 2005 Western Australian Exploration 1826-1835, The Letters, Reports & Journals of Exploration and Discovery in Western Australia. Vol 1. Victoria Park: Hesperian Press.

Stormon, E.J. 1977 The Salvado Memoirs. By Dom Rosendo Salvado, O.S.B. Translated and edited by E.J. Stormon. Nedlands: University of Western Australia Press.

Thieberger, N. and W. McGregor 1994 Macquarie Aboriginal Words. Macquarie University, Sydney: The Macquarie Library Pty Ltd.

White, I. (Ed.) 1985 The Native Tribes of Western Australia. Canberra: National Library of Australia.

Whitehurst, Rosemary 1992 Noongar Dictionary: Noongar to English and English to Noongar. Compiled by Rosemary Whitehurst. First Edition. Bunbury: Noongar Language and Culture Centre.

Hands up! Let’s go to The Humps and Mulka’s Cave