Some notes on Banksia usage in traditional Noongar culture

Prepared by Ken Macintyre and Barb Dobson

Research anthropologists

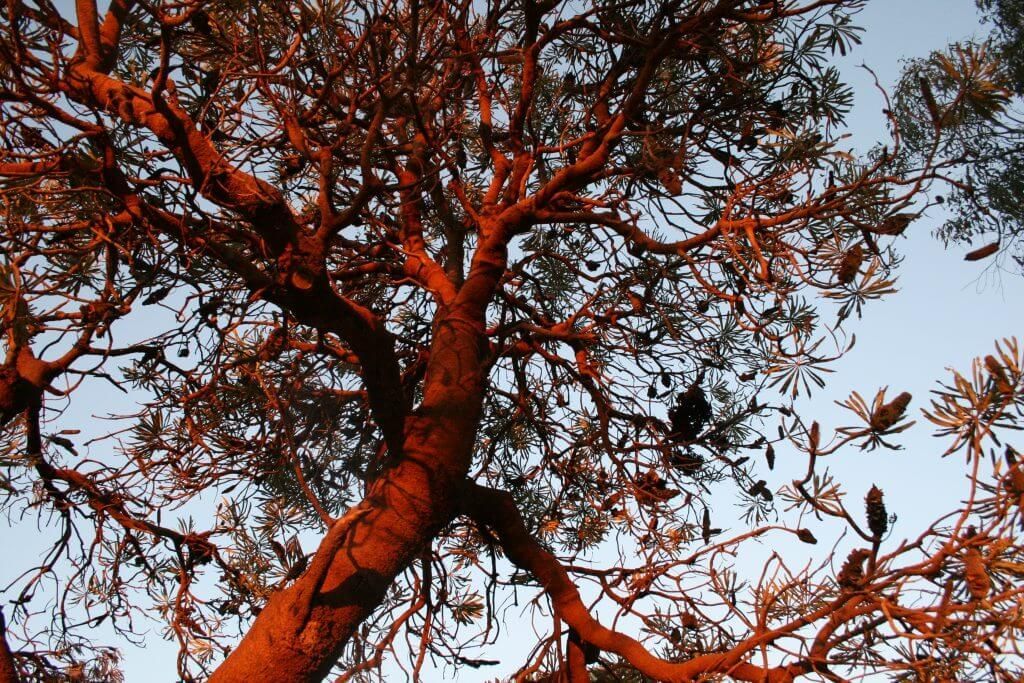

Cultural knowledge determines what we eat, the timing of eating and how food is prepared. Probably in the distant past when the original inhabitants of this land were adapting to their new environment, they ate certain plant products (roots, berries, gums and fruits) that made them ill or even killed them. From these trial-and-error experiments and empirical observations over many thousands of years, a rich and scientific traditional knowledge developed that determined which foods could be rendered edible through traditional processing methods. Natural indicators, such as insects, birds and marsupials, were used to determine the physiological ripeness and readiness for harvest of plant foods. In this paper we examine some traditional Noongar uses of Banksia products, in particular, Banksia nectar, especially how and when it was consumed.

Banksia nectar consumption taboo

Nowhere in the ethnohistorical or ethnographic literature of indigenous southwestern Australia could we find any reference to the consumption of “honey” produced by native bees. All terms referring to honey were describing flower nectar of one type or another. Banksia nectar, often referred to as ‘honey,’ is the main focus of this article. It was commonly known as mangite (or mangitch, mangyt, mungitj, mangaat, moncat, mangaitch, mungyt etc) or nguk (ngok or ngook). 1

We cannot over-emphasis the importance of the physiological “ripeness” factor when procuring indigenous fruits and nectareous products. This was empirically demonstrated in Noongar culture by a taboo on the consumption of not-yet-fully mature Banksia flower nectar. This prohibition was first noted by the Native Interpreter, Francis Armstrong in 1836 (in Green 1979:190):

‘the “Mungite,” or flower of the honeysuckle or banksia, must not be eaten too soon in the season, otherwise bad weather is sure to ensue.’

Bates (in White 1985: 199) also emphasises that the Mungaitch borungur (Banksia totem people)

‘must not pick the honey bearing flowers too soon, or great rain will come and very little honey will be gathered.’

The heavy rain would spoil the nectar crop by diluting its content and washing it from the flower. As with many taboos the cultural rationalisation here is not clearly stated. The message is designed to deter and to induce fear into potential taboo-breakers. The underlying practical reason is probably that the consumption of mungit out-of-season and before it is fully ripe may give the consumer a bad stomach ache or even worse. Similarly we are told in our own culture, albeit without the fear of such tragic climatic consequences, not to eat unripe fruit in case it causes a stomach upset. Chemical analysis shows that Banksia flowers at this early stage of the flowering cycle possess a high phosphorous and nitrogen content (George 1981 in Abbott 1985) which would explain why the ingestion of the not-yet-fully ripe nectar-bearing flowers (containing high concentrations of these and other chemicals) would have caused sickness.

Indicators of Ripeness of Banksia Flowers (mungyte) and complementary protein-catch

Birds and other animals were traditionally used as food-ripening indicators. In mid-late spring when members of the parrot tribe began to feed on the rich nectar-bearing flowers (mungit, mangite) of Banksia they were openly advertising the ripeness and readiness of these nectar-containing flowers for human procurement.2 The flowers attract numerous insects that in turn are predated upon by insectivorous birds and arboreal marsupials. Humans, birds and marsupials were all competitors for the sweet nectar. The association of parrots (Psittaciformes) and possums with flowering Banksia is well acknowledged in Noongar mythological narratives.

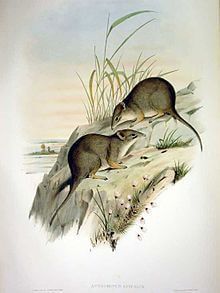

Small mouse-like marsupials and the tiny pygmy possum are also found in association with flowering Banksia woodlands where they feed on nectar, insects or small vertebrates. Some of these have been recorded by Grey and Moore rather vaguely as “species” of native mice. See list of Noongar names extracted from Grey and Moore’s original wordlists in Annotations. 3

Moore (1842:4-5) records the term ballawara in the Perth region (or ballagar or bellogar in the north and ballard in the south) as referring to a ‘small squirrel-like opossum.’ He attributes this name (p. 9, 160) to ‘Petaurus Mairarus, the grey squirrel.’ We don’t have squirrels or squirrel gliders in Western Australia, so the name may apply to the brush-tailed Phascogale which is a ‘rat-sized, sharp-snouted hunter with a diagnostic black ‘bottle-brush’ tail’ or it could apply to a type of possum, such as the pygmy possum which is attracted to nectar-laden Banksia flowers. We wonder whether the name for Banksia recorded by Stokes (1846) as bealwra is perhaps a habitat descriptor indicating where the ballawara or be-al-wra (small possum or possum-like marsupial is found. In Aboriginal taxonomy plant, insect and animal names were often habitat descriptors. For example, in our Bardi paper we note that the edible insect larvae known as paluk at King George Sound were found in the dead and decaying Xanthorrhoea also known as paaluk, see here. Another example of a habitat descriptor is the name of the burrowing sand frog goya (also kooya or kuya) which burrows and breeds in sandy soil known as goyarra (kooyarra or kuyarra). There are many other examples of habitat descriptor names which we will leave for another time.

Some Noongar names have been attributed by Western recorders and researchers to particular species, such as mandarda to the Western pygmy possum and ngool-boon-gur (or noolbenger) to the honey possum. These two tiny marsupials were regular Banksia nectar feeders and they were traditionally highly valued by hungry Noongar hunters for their nutritious protein-containing flesh.

Western pygmy possum

According to University of Western Australia researchers, the Western pygmy possum (Cercartetus concinnus) ‘is endemic to the south-west corner of WA and parts of South Australia’ and it ‘is not endangered.’ They comment that:

‘The mouse-sized animal feeds on nectar, pollen, insects and other small animals, especially in woodlands of flowering eucalpyts and banksias.’ (The West Australian, Dec 10, 2014).

Menkhorst and Knight (2001: 88) describe this possum as

‘Nocturnal, arboreal, terrestrial; eats arthropods and nectar.’

The Noongar name commonly attributed to the pygmy possum is mundarda (Menkhorst and Knight 2001: 88). This name derives from the early records of Gilbert, Grey and Moore. For example, Grey (1840:89) records mundarda as ‘a small species of mouse, which is generally found in the tops of the Xanthorrhoea’ and Moore (1842: 68) records mandarda as ‘a mouse [of which] there are several indigenous species.’ Early newspaper accounts refer to the ‘pouched honey mouse,’ ‘brush-tailed pouched mouse’ or ‘tree mouse’ and the ‘door-mouse possum.’ These seemingly refer to the honey possum, brush-tailed Phascogale and the pygmy possum.

An article in the West Australian (1934) states that the mouse-like possum or what it refers to as the ‘door mouse possum’ or mundada ‘lives in wooded country’ and ‘is said to nest in the tops of dead grass-trees and holes in stunted jarrahs.’ In winter it hibernates living off the fat stored in its swollen tail but in summer its appearance is more ‘slender and mouse-like.’

Early colonial recordings of indigenous names are often vague and difficult to assign with accuracy to species, owing to the small size of these marsupials, their nocturnal habits which means that they are rarely if ever seen first hand and the fact that Noongar people did not follow a Linnaean speciation model of animal, bird and plant classification. And yet since colonial times Noongar names have been continuously assigned by Western recorders and researchers to species. This has resulted in much confusion and ethnographic distortion.

Dibbler

The mouse-sized carnivorous marsupial (Parantechinus apicalis) commonly known as the dib-bler or “Southern dibbler” also nests in the tops, dead trunks or under the skirting of the Xanthorrhoea as noted by Gilbert:

At Moore’s River the natives describe it as making a nest beneath the overhanging grasses of Xanthorrhoea. While at Perth its nest is taken either from the dead stump or from the upper grasses of the same plant, while at the Sound the natives constantly pointed out a nest of short pieces of sticks and grasses on the ground…'[under the shelter of the Xanthorrhoea]

(Whittell 1954 citing Gilbert, 1840’s field notebook, in Morcombe 1967)

Gilbert remarks that :

‘While at the Sound I obtained a female with seven young attached in the same manner as observed in A. leucogaster…‘ (Gilbert as cited by Whittell 1954 in Morcombe 1967).

The Antechinus leucogaster, referred to by Gilbert, or the yellow footed Antechinus ‘eats mostly invertebrates, also small vertebrates, eggs, nectar..’ (Menkhorst and Knight 2001: 54). Gilbert records three different Noongar names under the heading of Antechinus in his field notebook (Whittell 1954 cited in Morecombe 1967). These are dib-bler (at King George Sound), wy-a-lung (at Perth) and marn-dern (at Moore River).

The dibbler (now Parantechinus apicalis) was considered extinct for some 83 years until re-discovered in the Albany region in 1967 by Michael Morcombe.4 Menkhorst and Knight (2001: 58) describe it as ‘solitary, mostly nocturnal’ ‘forages for invertebrates and small vertebrates in leaf litter, also climbs shrubs for insects and nectar.’ When Gilbert examined the stomach contents of a female specimen, it was found to contain ‘insects generally, but more particularly small Coleoptera.’ Given the dibbler’s habit of nesting in the tops and dead trunks and underneath the shady skirting of Xanthorrhoea, it no doubt also predated on fat-rich bardi – the white grubs of coleopterous beetles such as the longhorn beetle known as Bardistus cibarius which is commonly found in dead or decaying Xanthorrhoea habitat. See our paper https://www.anthropologyfromtheshed.com/the-puzzle-of-the-bardi-grub-in-nyungar-culture

The dibbler was only one of a host of small animals, including the Western pygmy possum, yellow-footed Antechinus, grey-bellied dunnart, brush-tailed Phascogale, honey possum (Tarsipes rostratus) and native bush rat (Rattus fuscipes) that were all attracted to the flowering Banksia habitat where there was a smorgasbord of insects, nectar and small vertebrates to prey upon. In turn these animal predators became the prey of Noongar hunters and nectar collectors, providing a favourable source of fat and protein. They were particularly relished when found with young ones attached.5

Honey possum – ngool-boon-goor

The mouse-sized honey possum (Tarsipes rostratus) is a highly specialised Banksia nectar feeder and pollinator. This iconic marsupial known as noolbenger derives its name from Grey (1840: 107) who first recorded ngool-boon-goor as ‘a species of mouse eaten by the natives’ at King George Sound. Moore (1842: 93) spells it as ngulbun-gur. In the Albany region ngull translates as ‘honey’ according to Coyne (1980). Early newspaper accounts commonly refer to it as ‘the honey mouse’:

‘The honey mouse was first made known to science through the efforts of Lieutenant (later Sir George) Grey, who discovered it in the late thirties [1830’s] at King George’s Sound. The little animal was known as the noolbenger to the natives of the district. Grey’s observations on the creature were quoted by John Gould in his great monograph on the mammals of Australia. He noted that Tarsipes was generally found in all situations suited to its existence from the Swan River to King George’s Sound, remarking that owing to its rarity and the difficulty with which it was procured only four specimens were obtained by the natives notwithstanding the high rewards offered.’ (The West Australian 1929).

Glauert, the Curator of the Western Australian Museum, points out that the ‘honey mouse’:

‘resembles the common ‘possum, and the little mundarda, all three of which have prehensile tails and, in all of them the hind foot is modified as an efficient grasping organ, the great toe being opposable to the others.’ (The West Australian 1929).

The honey possum (which is misleadingly named for it is not a possum, nor does it consume honey) feeds almost exclusively on nectar and pollen and traditionally formed a valued part of the human nectar-collecting process, prized for its sweet-tasting and protein-containing flesh. Honey possums often breed throughout the year, depending on food availability and will often be found with young ones in their pouch.

The honey possum has evolved a symbiotic relationship with the Banksia. In return for being the Banksia’s primary pollinator this small marsupial is rewarded with an abundant supply of energy-rich nectar and high protein pollen. It has evolved specialised physical adaptations including a thin snout and a long tongue with a brush-like tip enabling it to penetrate deep into the dense nectar-laden flower cones. Furthermore, research by Sumner et al (2005) suggests that the honey possum has evolved the optical ability to discriminate ripe nectar-bearing Banksia flowers from immature unripe ones. This specialisation reduces energy loss and increases its efficiency to collect nectar and pollen in larger quantities.

We would suggest that indigenous people already understood these subtle ecological feeding strategies in animals and birds that formed such an important part of their food chain and survival. The honey possum was a reliable animal indicator that formed an integral part of Noongar food science. Its ability to distinguish between green unripe Banksia flowers and ripe ones would have been well understood by the honey possum totemists and also the mangyte totemists.

Mondianong – the season of young parrots and Banksia nectar collection (late Oct to mid-January)

The season known as mondianong in the southern region (see Collie 1834) was the parrot-breeding/ hunting season. This season commenced in mid-late October and extended to mid-January. It was the time when birds, especially young fledgling parrots, were hunted. It overlaps the season recorded by Nind (1831) at King George Sound as maungerman or bird nesting season.

The equivalent season to maungernan in the Perth/ Upper Swan area was possibly manga (literally, meaning a nest). (The stem word maunger, King George Sound, may be a variant of manga, Perth area). Some interpretations of the Noongar seasons include manga as a season. George Fletcher Moore (1842: 68) in his Descriptive Vocabulary under “manga” notes that

‘Robbing birds’ nests is a favourite occupation in the proper season of the year.’

During spring birds’ eggs were highly sought after as were the young fledgling birds, especially parrots. These foods were favoured for their nutritious fat-rich flesh. Hammond (HS /357, Vocabulary of the South West Aborigines p. 12) notes that

‘The natives mostly ate birds’ eggs raw, but they had a method of roasting eggs without breaking the shells and sometimes did roast them to eat.’

The season for young parrots in coastal southwestern Australia coincided with the flowering B. grandis and B. attenuata coming into nectar production. Moore records the name for this season at King George Sound as Mandyeena. He writes:

‘Mandyeena -towran tittle boy (i.e. young parrots), cockatoo tittle boy’ & so on, this being the birds’ nesting time.’ (Moore 1833 in Cameron 2006: 212)

Moore (1833) describes Noongar people in the Perth-Upper Swan region collecting and consuming Banksia nectar during the parrot fledgling season:

‘Three of the natives were here today. They had been sucking honey from what they call ‘Mangaat’, the flowering cone of the Banksia… This is the season now for young parrots. I am told that the natives suck the honey out of their bills which the mother has just fed them with from the Banksia flowers.’ (Moore 1833 Sunday 27th October in Cameron 2006: 291-2)

In the southern region Collie (1834) describes Aborigines collecting mungat at the commencement of the season known as Mondyeunung:

At this period (Mondyeunung of our tribe), comprising from the latter part of October to the middle of January, the Natives bring in considerable numbers of young parakeets, and some cockatoos, to exchange for food. In the commencement of it, too, they brought us a liquid they had long talked about, which they call mungat, and, from some similitude or other, compared it to our oil and to our honey. We had understood they collected it from trees, and some thought it was a manna, others a real honey; all imagined, as they set a value upon it, that it must be good. It proved in reality to be the nectareous fluid of the flowers of the banksia, and when collected and preserved, as they presented it, mixed with the foreign juices [saliva] not to be avoided in their mode of collecting. The stately cylinders of flowers of the trees in question are not submitted to coction [decoction] in water to extract the honied treasure; the mere summary process of suction by the mouth is far more convenient, and the apparatus is more portable, it being then ejected into a bottle [traditionally probably a paperbark vessel] previously obtained for the purpose. The natives themselves appear to esteem this a great luxury, and, in the season, their dingy beards and large lips are powdered with the pollen of the flowers.’ (Collie in Green 1979: 82)

The attraction of parrots and other birds to flowering Banksia spikes is well recorded (Collie 1834, Moore 1834 and others). Ethel Hassell (1975: 108) writes:

‘… there are always plenty of parrots around the rivers and swamps when these plants [Banksia] are in bloom, besides numerous small birds.’ (1975: 108)

Rival avian competitors for nectar include a range of honey-eating birds, especially iconic members of the parrot family, such as the Western rosella (Platycersus icterotis), red-capped parrot (Purpureicephalus spurius) and the Australian ring neck (Barnardius zonarius). These brightly coloured, noisy nectar and insect predators herald the start of the mungite season. Honey-eaters, wattle birds and other small birds also raid the nectar. Even the black cockatoos and Western corellas that feast on the Banksia seeds and insect larvae found in the bark and fruit, also consume the flowers and nectar (see Plates 3-7).

The parrot mob were the caretakers of the little birds. If they see a hawk hanging about, they call out ‘danger.’ (Noongar Elder, personal communication 1992).

Mondeunung is the name of the season at King George Sound from late October to mid-January (Collie 1834). Barker (1830) records it as mondianong (also as mondianny, mandiarany, mandianary, see Mulvaney and Green 1992: 420). Barker’s scrawled handwriting when viewed on microfilm at the Battye library is exceedingly difficult to decipher.6 In attempting to translate the term mondianong, using all the available Noongar wordlists at our disposal, we came across mondyit as the name recorded by Hassell (1890’s) as “rosella.”7 The Western rosella is endemic to southwestern Australia. Could this colourful broad-tailed parrot symbolise the season of mondianong when young fledgling parrots and their kin were hunted and their eggs collected?

‘As the season [September/ October] advances, they procure young birds and eggs, and their numbers increase. About Christmas they commence firing the country for game.’ (Nind 1831 in Green 1979: 35)

Barker (1830) refers to a large and important ceremony known as the maint (which he also spells as myntte or maintye) that took place in the southern region in mid-late October. This was a time of seasonal transition towards the end of Minangal (early spring) and the beginning of Mondianong (late spring/ early summer). These seasons roughly correspond to jilba (late winter/ early spring) and kambarang (mid-spring to early summer) in the Perth region.

The ceremonial maint involved much planning and preparation, and according to Barker (1830) induced great excitement among the local indigenous population at King George Sound. He describes a prominent female maint totemist adorning her body with bird feathers in preparation for the maint ceremony to be held at Cojinnerup. The name for “white cockatoo” or long billed Western corella is manyt (or manyte, manhyte, minnit, minat, manitch, manite, manhyt). Barker’s (1830) myntte (or maint, maintye) may be regarded as synonymous with Nind’s (1831) minnit, meaning white cockatoo. The maint ceremonial gathering (or what other recorders called mant, mund-ja, mandjar) was a much-anticipated social-ceremonial and economic event that attracted large numbers of people from all the surrounding districts. It celebrated the coming together of groups of people who had been dispersed during the winter and early spring. These ritual celebrations involved white cockatoo totemists who were familiar with and celebrated the nesting and fledgling cycle of the totemic white cockatoo which symbolised the season of increased light intensity, warmth and fertility.

These large seasonal spring gatherings also included a mandjar or type of fair where valued cultural items, such as boomerangs, shields, spears, ochre, stone knives, axes, kangaroo skin cloaks and certain foods were exchanged. Moore (1842: 68) describes how products from the different regions were exchanged like ‘an interchange of presents, than a sale for an equivalent.’ Von Brandenstein (1988: 8) refers to it as mant or maanty. Communal hunting also took place (e.g. kangaroo hunts) to ensure a plentiful supply of food for all the visitors. It was at this time that female kangaroos were often de-pouching their young.

Traditionally the white cockatoo is totemically and mythologically significant to Noongar people. It was the totemic symbol of the manitchmat or white cockatoo moiety, which comprised one of the “halves” of traditional society while the other “half” was known as wardongmat symbolised by the black crow (more properly known as the Australian raven). The white cockatoo symbolised the “light” moiety while the crow represented the “dark” moiety. These moieties governed the marriage laws which stipulated that a member of the manitchmat must marry a member of the wardongmat and vice versa. No one could marry within their own moiety.

The white cockatoo announced the beginning of the day – the arrival of daylight. Barker (1830) describes this as the “cockatoo crow” as opposed to our notion of the “cock-crow.” See our paper on ‘Daytime reckoning: Light time in traditional Noongar culture.

In a metaphorical extension of the day/ night cycle into the seasonal realm, the white cockatoo (manyt, manet, munitj, munet) may be seen as announcing the beginning of the bright light season of spring/summer. The spring/summer flowering of selected Banksia attracted people back to the coast where they congregated in large numbers to conduct their mandyars and to hunt, fish and celebrate the beginning of the warm bright light season. It would seem that photoperiodicity was instrumental in regulating all aspects of indigenous culture.

The Mungyt-eating season – when was it and how long?

Grey (1840: 71) records the mungyte – eating season or what he records as “mun-gyte backan-een” as kum-bar-ung ‘about October.’

It would seem that late October/ November was the beginning of the nectar-eating season in the Perth area. This was the time when the flowering cones of B. grandis (Bull Banksia) and B. attenuata (slender Banksia or candle Banksia) were coming into nectar-production. The quantity of nectar production and timing of collection depended on a number of factors including the Banksia species, unseasonal weather events in the preceding months or years, fire history, geographic locality, soil type and whether the Banksia consumption taboo had been properly observed. Moore (1833 in Cameron 2006) refers to the mangaat being consumed in late October.

A number of early European observers were impressed by the majestic and magnificent splendour of Banksia grandis in the Perth area (Drummond 1839, Backhouse 1843). As early as 1827 Fraser (cited in Shoobert 2005: 49) observed that:

‘From Pelican Point to the entrance of the Moreau [Canning River], the country is diversified with hills of gentle elevation, and with narrow valleys, magnificently clothed with trees of the richest green. Here genus Banksia appears in all its grandeur, consisting of three species, of which B. grandis is the most conspicuous.’

At Point Fraser, Banksia grandis was observed to

‘attain the height of fifty feet, and its trunk frequently exceeded two feet and a half in diameter’ (in Shoobert 2006:51).

Bunbury (1930:80) in Meagher (1974: 33) notes that in the lower south-west region

‘December is the season for “munghites” ‘as they call the flower of the Banksia, from which they extract by suction a delicious juice resembling a mixture of honey and dew.’

J.S. Roe (1835 in Shoobert 2005: 511) in his diary entry for 16th December 1835 at Kings Georges Sound refers to

‘the liquid honey which at this season of the year is to be found in the rich looking yellow flower of the banksia.’

An even earlier reference for the Albany area is provided by Cunningham who was the botanist accompanying Captain Phillip Parker King and John Septimus Roe on board The Mermaid at Oyster Harbour in 1818. He refers to flowering B.grandis in the latter part of January:

‘On the barren, dry, stony hills and grounds rising from the beach Banksia grandis arrests the attention of the collector more particularly than any of its kindred indigenous around it. It forms a small tree of irregular growth, is very abundant, and at this season is in flower and young fruit.’ (21st January 1818 Cunningham’s diary entry, Oyster Harbour area, Albany)

The following day Cunningham observed B. attenuata in flower:

‘Banksia attenuata, whose stems, although short, were 24-30 inches in diameter, and at this time in flower and young fruit.’ (22nd Jan 1818 on the shore between KGS and Oyster Harbour.)

The earliest observation and recording of indigenous people in Western Australia collecting nectar from Banksia is provided by Nind (1831 in Green 1979: 33) at King George Sound:

‘When the different species of Banksia first come into bloom, they collect from the flowers a considerable quantity of honey, of which the natives are particularly fond, and gather large quantities of the flowers (moncat) to suck. It is not, however, always to be procured; the best time is in the morning when much dew is deposited on the ground; also in cloudy, but not wet weather.’

Drummond (1842) notes, referring to the King George Sound area, that:

‘Cunningham observes that B. coccinea and B. grandis are the pride of King George’s Sound; there the B. grandis is a mere shrub compared to how it grows at the Swan River.’

Von Huegel (1834 in Clark 1994: 85) provides another early description of Aborigines sucking the nectar from Banksia flowers at King George’s Sound.

‘On my way home I met Lindolf, who had renounced all his fine raiment and was wandering about in the woods stark naked, picking the fruits of the Banksia trees and sucking them. I asked him the name of the Banksia dryandroides, long cones of which he had in his hand, and he replied: ‘Manyat’. Banksia coccinea is ‘Waddib’ and Banksia occidentalis is ‘Pia.’ This shows that the natives of New Holland have a more highly developed language than has hitherto been acknowledged.’ (Von Huegel 5th January 1834)

The botanist Von Huegel (1834), like many of his contemporaries of the time, believed that his Aboriginal informants were describing different Linnaean species of Banksia when in fact they were using indigenous descriptors to explain the cultural significance of Banksia products: how they were identified, used and sometimes significant animal/ bird attractants. It is possible that the descriptor term waddib recorded by Von Huegel for Banksia coccinea (Red Swamp Banksia) may be an abbreviated version of the term dib-bler or alternatively, a type of possum known as waiada or wawding (ringtail possum) often found in flowering Banksia habitat. (wawding, wawd-ip, wawdup, place of). These animal protein sources were highly prized by Noongar hunters and waist belts known as nulbarn (or nulboo) were made from the possum fur.

Some Noongar descriptor names for Banksia include manyat, moncat, mangaat, mangyt, mungyt, mungite, munghite, mungat, mangite, mangaitch, mungytch, mang-ghoyte, waddib, beera, biara, piarar, pira, pia, nugoo, gnook, be-al-wra, boolgalla, bulkalla.

Nind’s (1831) moncat, Moore’s (1833) mangaat, Von Huegel’s (1834) manyat, Stokes (1846) mang-ghoyte and all synonyms which refer to the nectareous flowers of the Banksia. There are numerous variant renderings including mungyt, mungyte, mungite, mangaitch, munghite, mangite.

Stokes (1846) records two names for Banksia:

Honeysuckle: Mang-ghoyte: Banksia: large flowering cones containing honey.

Honeysuckle: Be-al-wra: Banksia: large flowering cones containing honey.

The same plant or family of plants can have a number of different names, depending on what is being referred to from the indigenous point of view. For example, mang-ghoyte describes the sweet nectar that is sucked or soaked by Noongars to extract the sweet honey and be-al-wra possibly denotes the ‘small squirrel-like opposum’ (or ballawara, Moore) found feeding on the nectar.

Von Huegel’s pia may be viewed as the same as Grey’s (1840:112) peera and Moore’s pira all recorded for Banksia species at King George Sound. Lyon (1833 in Green 1979: 171) also records beera as the name for Banksia grandis in the Perth area. Moore records biara as Banksia nivifolia but since this species is not found in Western Australia he was probably referring to B. attenuata for he describes it as having

‘long, narrow leaves, colloquially honeysuckle.’

The same Noongar term (pia, pira, peera, beera, biara) is assigned to different species by different recorders; for example, Von Huegel assigns it to B. occidentalis, Lyon to B. grandis and the linguist Von Brandenstein (1979) attributes piarar to both B. grandis and B. attenuata while Drummond attributes the name mangite to B. grandis.

As tempting as it is to attribute indigenous names to familiar Linnaean defined species, this is most unhelpful when it comes to understanding traditional plant descriptor terminology for Noongar terms had a practical, utilitarian, totemic, symbolic or mythological significance appropriate to a traditional hunter-gatherer-fisher culture (Macintyre and Dobson 2017, unpublished notes on Noongar descriptor plant nomenclature)

Pira the term recorded by Moore (1842: 94) referring to ‘a species of Banksia’ at King George Sound may also be interpreted as symbolising light (biryt light, daylight, firelight) for the Banksia flowering season heralded the beginning of the hot bright light season known as pirok (or peeruck, beruc, birok, birak). Salvado (1851) and Curr (1886) translate pirak as meaning ‘day’ and piraggi as ‘the light of day’ (in Bindon and Chadwick 1992: 151). The indigenous name for Banksia may be seen to symbolise of the season of light, warmth and fire.

What is interesting is that the dark/ light seasonal divisions of Noongar culture (“dark” season and “light” season) may be seen to be modelled on the day/ night cycle but on a grander scale marking the ebb and flow of light intensity throughout the year. From this perspective the light season symbolises daylight and the dark season represents the darkness of night.

The length of the mangite season would have varied, depending on seasonal factors. Drummond (1839) writes that the ‘native mangite‘ season lasted for about five to six weeks. Referring to the Banksia grandis, he writes:

….the spikes of the flowers [were] from fourteen to sixteen inches; the natives, men, women and children live for five or six weeks principally upon the honey which they suck from the flowers of this fine tree.’ (Drummond June 1839)

Florabase (2009) records the flowering period of B. grandis as Sept to Dec (or January). However, research by Scott (1982) cited by Abbot 1985: 129-131) suggests that the period of Banksia grandis mature inflorescences is very short-lived:

‘Growth of the immature inflorescence took four to eight weeks but maturation (exsertion of styles) lasted only two to three weeks. On the coastal plain near Perth these times were four weeks and two weeks.’

The Banksia flowers on a particular tree or grove of trees do not all reach maturation point at the same time. The full spectrum of the flowering cycle is often visible, for example, some flowers are still green, others partially mature, others fully mature and others are in senescence. The Noongar nectar collectors were fully aware of this and were in strong competition with their nonhuman rival nectar raiders for the honey-laden mangyt, which Moore (1842) describes as follows:

‘The large yellow cone-shaped flower of the Banksia, containing a quantity of honey, which the natives are fond of sucking. Hence the tree has obtained the name of the honeysuckle tree. One flower contains at the proper season more than a table-spoonful of honey. Birds, ants, and flies consume it’ (Moore 1842: 69)

Abbott (1985: 139) also refers to the abundant nectar found in the flowers of Banksia grandis. He says:

Nectar was copious….Sugar content averaged 25 % (range 19 to 45 %, n = 9)

Hassell (1936) refers to the Banksia as a ‘honey plant.’ Certain Dryandra species (now called Banksia) are called ‘couch honeypot.’ As already noted, Curr (1886) records the meaning of mungite as “sweet.” The term nugoo which also refers to Banksia nectar similarly means sweet, honey, nectar and may even refer to the sucking action, describing how the nectar is consumed by sucking through the teeth or nalgo (teeth, ‘to eat’). Plant descriptors sometimes conveyed the means by which a particular product was consumed, for example, galyang, Acacia gum, possibly describes how it was chewed. See our paper http://anthropologyfromtheshed.com/the-sweet-gum-a-nyungar-confection/

Meagher (1974:60) mistakenly records nugoo as the species’ name for Banksia sphaerocarpa (the round-fruited Banksia). The information provided by her Aboriginal informant Nellie Parker (20 August 1967) from the Mingenew area describes the term nugoo as:

‘The nectar from the spikes of a Banksia. On a wet day the nectar is sucked straight from the spikes, at other times the spikes are soaked in water for a few minutes [sic] and then the water is drunk.’

Nugoo is a generalised descriptor term referring to honey or nectar. This is demonstrated by E.A. Hassell (1975) who records gnook as ‘honey from Banksia;’ Douglas (1976: 70) records ngug as ‘honey’; Dench (1994) records ngok and nguka as ‘honey from banksia’ (ngok, in the south and east regions and nguka in the north and southwest region) and Nyoongar linguist Whitehurst (1992: 21) also records ngook as ‘honey.’

The timing and length of the mungyte-eating season varied in southwestern Australia depending on geographic and climatic zones and the different Banksia species coming into nectar production at different times. Variability in climatic conditions, localised weather conditions and the potential violation of traditional Banksia nectar-consuming laws and taboos, could affect seasonal supplies. It was for this reason that the Banksia nectar totemists meticulously carried out Banksia nectar increase rituals. According to Bates (in White 1985: 199) these totemic increase rites were carried out in the Perth region in early winter to ensure a plentiful supply of mungaitch:

‘To make an increase in the honey bearing flowers of the banksia, the mungaitch borungur of the Swan and Pinjarra districts ochred themselves, and gathering leaves and small branches of the banksia in early winter, they rolled these together and placed them in the forks of the tree. Wordungmat [Crow moiety] and Manitchmat [White cockatoo moiety] took part in this ceremony every winter.

The prolonged period of Banksia flowering and nectar production at King George Sound from late October (Collie 1834) to late January (Cunningham 1818) is probably explained by the different Banksia species coming into nectar production during this period. A number of species are mentioned by the early recorders at Albany. These include B. grandis, B. attenuata, B. dryandroides, B. coccinea and B. occidentalis.

Geographic locality, species and flowering conditions determined when the nectar was collected. For example, the nectar-consuming season for Banksia candolleana (Propellor Banksia) in the Eneabba-Gingin area was from April to early August (Bindon 1996: 50).

Doobarda – a species of mangyte – a late-flowering Banksia

Grey (1840:30) records doo-bar-da as ‘a species of Mangyte’ but he does not elaborate as to which Banksia he is referring. Moore (1842: 24) attributes dubarda to

‘The flower of a species of Banksia which grows on the low grounds and comes into flower the latest of all these trees.’

We are unsure which Banksia this refers to but it may be one of the swamp banksias (e.g. B. littoralis) which has large nectareous flowers from March to June (see Plate 20 below). The swamp banksia is also known as boongura (Lyon 1833 in Green 1979: 171).

Boongura – Swamp Banksia

Lyon (1833 in Green 1979: 171) records boongura as ‘Banksia, swampy species.’ The literal meaning of the term boongura is unclear. It may be a descriptor referring to the ngora or Western ring-tailed possum that is often found in association with flowering Banksia and much sought after as it provided a rich source of protein and fat. (ngora, see Grey 1840: 107 and Moore 1842: 92). Other recorders spell it ngawar-ra or ngwarer.

Ngura also means ‘a small lake or basin of water’ (Moore 1842) or ngura, a spring, pool (Salvado 1851 in Stormon 1979) or ngoo-ra ‘a small lake or basin of water’ (Grey 1840: 107) or ‘lake’ (Lyon 1833). At the time when swamp banksia first came into flower (March) the water courses along the Swan Coastal Plain would have been in many places reduced to small pools as noted by Moore in his diary entry (14th April 1835) ‘the water, which now stands in pools at irregular intervals’ in the bed of Ellen Brook. These small pools of water together with the flowering boongura and associated marsupials would have provided sustenance for family groups before being replenished by the winter rains.

Another late-flowering species of Banksia (Banksia prionotes) is the Acorn Banksia which flowers from Feb to August (see Plates 16-17). Although this plant is not confined to low lying areas, its nectareous flowers are popular with honey-eaters, cockatoos and many other birds and would have been sought after by Noongar people if the flowers contained sufficient quantities of nectar. Another late-flowering Banksia is the Firewood Banksia. According to WA Florabase it commences flowering in late summer (February). Drummond (1842) refers to Aboriginal people sucking the nectar-laden flowers or mangite of B. menziesii as well as B. caleyi and B. vercillata. Could the nectar of the firewood Banksia (see Plates 18 & 19) be a type of doobarda?

The linguist Von Brandenstein (1988:176) lists five different species of Banksia nectar consumed by Noongar people. These included B. grandis, B. attenuata, B. nutans, B. occidentalis and B. pulchella. He records the name of the first two species as “piarar” and the other species as follows:

(i) B. nutans R.Br. “honey out of cones” taaaliny The term taaaliny as noted by Von Brandenstein himself literally means “tongue.’ We would suggest that this term is an indigenous descriptor explaining how the nectar is licked out of the cone using the tongue (taling, tarling). Salvado 1851) records talan-an as meaning ‘to lick.’ Contrary to what Von Brandenstein would have us believe, taaaliny, is not a species name.

(ii) B. occidentalis R.Br. Noongar name, waaly (Von Brandenstein 1988: 166). As we have already noted Von Huegel (1834) attributes the Noongar name pia to this particular species.

(iii) B. pulchella R.Br.- “like pine needles, honey in July”, tuuaatt-e-yiar (Von Brandenstein 1988: 166)

Once the meaning of a Noongar term is known, it is easier to understand the dynamics of indigenous plant taxonomy. However, Von Brandenstein (1988) like his colonial predecessors, and even researchers to this day, is attributing Noongar terms to the different Linnaean species as if assuming that indigenous plant nomenclature followed an 18th century Western-derived Linnaean speciation model. Such Western-centric assumptions must be challenged rather than perpetuated by anthropologists, archaeologists, botanists and ecologists.

Back to the mysterious identity of dubarda, which Grey and Moore believe to be a type of Banksia that flowers later than the other mangyte producing Banksias (namely B. grandis and B. attenuata). Initially we thought that dubarda may be a seasonal descriptor indicating the time of year when the nectar from this particular Banksia was consumed. Our reason for this particular interpretation is that Grey (1840) records the linguistically similar term dulbar as late autumn (April/ May) and da translates as ‘mouth’ or ‘to eat,’ hence one could speculate that dulbarda is a variant rendition of dubarda. Compound words are common in the Noongar language and when broken down and translated, their meanings sometimes become apparent. But we are not linguists, so we can only guess using our anthropological imagination. Knowledge of the optimal seasonal timing of the consumption of a particular plant product (such as the gum, seed, root, nectar) was critical for sustenance and survival purposes.

Preiss (1837) an early botanist records tubada as Callistemon phoeniceus (lesser bottlebrush). Based on this attribution to species, Powell (1990: 76) recommends that toobada be adopted as the common name for Callistemon phoeniceus, believing it to be more suitable than its current name of ‘lesser bottlebrush.’ If Moore’s description of doobarda as a late flowering Banksia species is correct, this would rule out Callistemon which is neither a Banksia nor a late-flowerer, for according to WA Florabase it flowers from Sept to January. This is around the same time as the flowering phenology of B. grandis and B. attenuata. It is entirely possible that the descriptor name doobarda applies across genera to describe the mangyte-like nectar of Callistemon as well as Banksia in which case it is not a seasonal descriptor as we first proposed.

If only the early recorders had made a point of asking their indigenous informants to translate the meanings of plant, bird and animal names and we wouldn’t be in this foggy predicament. Had they done this, it would have given us an enormously valuable insight into indigenous botany, ecology, seasonality and further enriched our understanding of indigenous traditional knowledge of plant, bird and animal behaviours, habitats and phenological breeding cycles.

Dubarda may have encompassed more than one species of flowering plant whose nectareous flowers were sucked or soaked for the purpose of extracting the much relished nectar. The Noongar consumed nectar from a wide variety of flowers throughout the year including Banksia, Dryandra (now classified as Banksia), Hakea, Grevillea, Callistemon, Calothamnus, Jarrah and Marri. The marri flowers were steeped in water ‘mangyte style’ in March, see our paper http://anthropologyfromtheshed.com/project/the-sweet-gum-a-nyungar-confection/

Noongar names – butyak, budjan (Banksia fraseri, B. sessilis and B. nivea – formerly Dryandra)

Moore (1842: 23) attributes the Noongar name butyak to Dryandra fraseri. However, his description fits Dryandra sessilis, now Banksia sessilis.5

butyak – ‘…The flowers are thistle shaped, and abound with honey; they are sucked by the natives like the Man-gyt or Banksia flowers.’

Moore (1842: 19) attributes the Noongar name budjan to Dryandra fraseri (now Banksia fraseri).8 He writes:

‘budjan – Dryandra Fraseri (a shrub). The flower abounds in honey, and is much sought after by the natives. See butyak’

Interestingly, Moore also records budjan as meaning ‘to pluck feathers from a bird’ (1842: 19). We would suggest that budjan may be an indigenous descriptor that describes how the bird-like feathers of this Banksia flower were “plucked” to obtain the prized nectar from the “honeypot.”

Moore (1842: 92) emphasises that the flower of the budjan ‘abounds in honey’ and records ngon-yang as ‘the honey or nectar of flowers,’ also ‘sugar.’

Preiss’ (1837) attributes budjan to Dryandra nivea (now Banksia nivea). Its common name is “Dryandra honeypot.” We would suggest that B. fraseri and B. nivea were both highly valued as nectar-pots and known by the same descriptor budjan. As we have previously noted in many of our papers, the assigning of Noongar names to Linnaean-defined species is highly problematic and ethnographically misleading.

Since Noongar people did not differentiate Linnaean-defined species as we know them, attempts by Western trained ecologists, ethnobotanists and archaeologists to try and fit Noongar names to individual species has created nothing but confusion. It is very difficult to take off our Western-centric Linnaean-blinkers and try to understand Noongar taxonomy from the perspective of a traditional hunter-gatherer economy (Macintyre and Dobson 2009, unpublished notes).

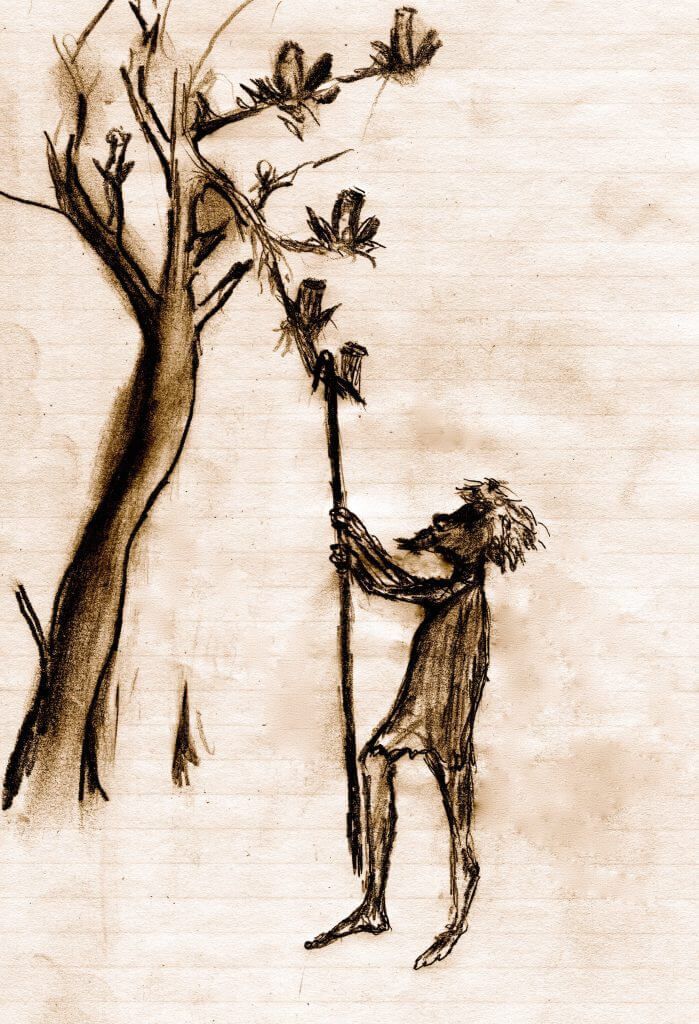

Traditional collection and fermentation of Mungyt (Banksia nectar)

Grey (1840: 83, 91) refers to kal-ga as the stick for hooking down (p. 83) or pulling down (p.91) the flowering Banksia cones. He refers to this stick as the ‘mungyte-bringing agent’ or “mungyte bur-rang midde” (p. 59). Moore (1842:38) likewise records the name of this hooked stick as kalga:

‘A crook. A stick with a crook at each end, used for pulling down the Mangyt, or Banksia flowers.’

The nectar producing flowers of selected Banksia were often sucked or alternatively, soaked in water to extract the highly valuable nectareous fluid which was drunk as an energy-rich beverage. Sometimes this concoction was left for a period of time to ferment with naturally-occurring wild yeasts creating a mild alcoholic mead. Roth (1904:49), who cites Austin’s observations in the Bunbury/ Leschenault Inlet area, graphically describes the traditional methods of collecting and processing Banksia nectar or man-gaitch in southwestern Australia. He writes:

‘Narcotics were unknown. Upon this sandy tract of country, extending back as it did to some considerable distance from the coast, two species of Banksia grew abundantly, one conspicuous by its broad leaf [probably Banksia grandis] the other by its narrow leaf [probably Banksia attenuata]. Each species bore cones with pitcher-shaped flowers, which, containing a quantity of honey, were especially visited by the black cockatoos. The natives appreciated the honey also, and, pulling down the cones by means of a long sapling (close to the extremity of which was tied a cross-piece about 9 inches or 10 inches long, somewhat after the shape of a sheep crook*), would bite into them and suck the saccharine matter out. At other times they utilised the honey by making a fermented drink of it, somewhat on the following lines :—Large quantities of the flower-bearing cones were taken to the side of some swamp, in the close proximity of which several holes were dug into the ground, each in the form of a trough about a yard long and 18 inches deep. Particularly sound sheets of tea-tree bark were next stripped from the trees, each piece of bark being tied up at the ends with fibre into a sort of boat-shaped vat, the sides of which were kept apart by sticks stretched across; the shape of the vat lent itself to that of the trough, and there was one vat for each trough. The vat was next filled with these cones and water, in which they were left to soak. The cones were subsequently removed and replaced by others until such time as the liquid was strongly impregnated with the honey, when it was allowed, to ferment for several days. The effect of drinking this ” mead” in quantity was exhilarating, producing excessive volubility. The aboriginals called the cones and the fermented liquor produced therefrom both by the same name—the man-gaitch’ (Roth 1904: 49).

Fermentation was practised by Noongar people not only in the brewing of this mild ceremonial intoxicant but also in a different way in the seasonal processing and storage of the red Macrozamia fruit known by Noongar people as by-yu (or baio, booyo). See article written by Mark Cornish http://anthropologyfromtheshed.com/project/macrozamia-sarcotesta/

Banksia nectar was sucked and in some cases fermented in other parts of Aboriginal Australia, such as Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria. Palmer (1883) documents the indigenous consumption of the nectar of Banksia marginata in Queensland where it was known as “wallum.” He writes:

‘A stunted honeysuckle, growing in poor sandy country, north of Wide Bay, along the coast. The honey is sucked out of the flowers by the natives at certain seasons by drawing across the mouth. They gather from all parts [of the country] when the flowers are full, and are very partial to it.’

Mungyt seasonal gatherings at South Perth

Bates (1906) describes two locations where seasonal mungytch ceremonies took place. These were at South Perth and the shores of Mt Eliza/ Kings Park:

‘The tongue of land at South Perth, now known as Mill Point, was the property of Karreen and was inherited by him and his brother Beenan, from their father. This place was known among the Perth natives as Karreenup, Karreen’s place, yet Beenan inherited it equally with Karreen. Still Karreen being the elder brother, the place was known as Karreen’s place, “Karreenup.” The honey bearing Banksia grew abundantly at this point and was the totem (borongur – elder brother) of Beenan…’ (Bates, Notebook 20,12th April 1906: 56)

The totemic significance of mungyt is further noted by Bates (1906:43) who records the alias name of one of her informants as Ngoker. This name, she says, derives ‘from sucking mungytch. …(ngoko = sucking, sweet)’.

‘The mungytch is Ngoker’s “borongur” [elder brother, totem]

Bates (in Bridge 1992: 23) refers to the scenes of fighting, feasting and merriment involving mungaitch:

‘At South Perth, where a quantity of honey-bearing banksia (Mungaitch) grew, the time of its flowering was made the occasion for a visit from all the surrounding Kallipgur, Murray River people included, and great was the feasting and fighting. There is, or was, a very fine spring on the Melville Water side of South Perth, and during the visit of the Kallipgur the spring was generally widened and the honey-laden flowers were thrown into the spring, fermenting slightly in the water. The decoction was eagerly drunk by all present, and generally made the “heavy” drinkers of it “Yow-er-ung,” the same term being used for a drunken native at the present day.’

Bates records wardaruk as the ‘bamboo grass made into tubes for drinking mangytch’ (1906: 45, Notebook 20). However, traditionally, according to Moore (1842: 63) they dipped ‘a bunch of fine shavings’ into the mangyt and then sucked on them:

‘To steep in water – as, Man-gyt, or Banksia flowers, in water, which the natives do to extract the honey, and then drink the infusion. They are extremely fond of it; and in the season their places of resort may be recognized by the small holes dug in the ground, and lined with the bark of the tea-tree, and which are surrounded with the drenched remains of the Man-gyt. They sit round this hole, each furnished with a small bunch of fine shavings, which they dip and suck until the beverage is finished.’ (Moore 1842: 63)

In late November 2007 Macintyre and Dobson experimented with soaking ripe Banksia flowers in water for two days, creating a crude concoction with a honey-scented odour, which tasted something like a light mead. It was not unpleasant to drink and gave a mild feeling of euphoria. When we discussed our experiment with some Noongar Elders, one of them explained that they already knew about this and that they called the fermented concoction geber (or giber). He added:

‘not only did we have our own grog but we also had our own chewing tobacco boolgar.‘

Boolgar is a local southwest Australia species of Nicotiana, possibly the round-leaved Nicotiana rotundifolia.

Mungyte seasonal gatherings at Perth Waters

Bates (1906) also describes the mangyt gatherings that took place on the white sandy shore near Mount Eliza (Kings Park):

‘White sand on the other side of Kareenup [South Perth], where the natives made a “soak” into which mungytch (or banksia) flowers were put, the natives drinking the sweetened water. (Sometimes a yorla or paperbark vessel held the water). The mungaitch fermented and the “honey beer” intoxicated the natives. There was always fighting at Gooyagarup during the honey-beer drinking season.’ (Bates, Notebook 20, 12th April 1906: 60)

It is obvious from Bates’ description that these were large seasonal ceremonial gatherings which involved a large number of groups from the surrounding districts. At these events inter-group relationships would have been consolidated, disputes resolved and economic and ceremonial exchanges (trading) would have taken place. These communal gatherings required advance planning and the provision of enough food to feed large numbers of people. This was the host group’s responsibility. The mangaitch alone would not have been sufficient to sustain them. In the Swan River area communal kangaroo hunts (e.g. kaabo or battue at Mt Eliza)) and fishing may have provided the required sustenance to feed visitors. This season was known in the Perth region as kumbarang. This term probably derives its meaning from coombar (big or large, Hassell 1936) referring to the coming together of large assemblies of people.

In the lower southern region there are accounts of the culturally important ceremonial gathering known as the maint or mantye which celebrated the totemic significance of the white cockatoo (manyt) heralding the beginning of the season of bright light and warmth. Barker (1830 microfilm) records the maint at Cojinnerup as commencing in mid-October. This occasion was also a communal means of establishing and reinforcing kinship ties and group identity.

‘The communal kangaroo hunt, which required large numbers of people cooperating as a single unit to surround and entrap the prey, symbolized this unity. The intergroup fighting that Browne so vividly describes may be viewed as a form of ritualised aggression which serves to get rid of old grudges and grievances which are held by the different groups assembling together for ceremonial purposes. The ritualised nature of the fighting explains why few serious injuries were incurred.’ (Macintyre and Dobson 2011: 26).

The Banksia seasonal gatherings along the coast were events that involved a degree of traditional scientific precision and a deep understanding of animal and plant phenology. It has only recently been discovered by Western scientists that Banksia flower profusion is highly dependent on length of daylight and increasing temperatures. According to Rieger and Sedgley (1996)

Day length and temperature stimulate vegetative growth and the development of more flower spikes in Banksia with some species responding more to increased day length (B. coccinea) and others to increased temperatures (B. hookeriana).

The timing of large-scale communal events was always carefully calculated using indigenous ecological knowledge that aligned predictable seasonal, ecological, phenological and even astronomical indicators.

Mungyt as an item of trade

In traditional Noongar culture where sweet-tasting products were highly valued, it is easy to understand why groups travelled, often long distances, to coastal areas such as Perth to eat the sweet mungite and to avail themselves of the fat-rich animal foods, such as kangaroos and possums, that were available at this time. October/ November was the season when female kangaroos de-pouched their young.

Hassell (1936: 689 1975: 108) records a mythological narrative that describes a family group’s odyssey to the coast to collect mungite which they had never before seen or tasted. The myth describes how

Degindie and his family ate of the mungite honey to their heart’s content, then in the evening used to hunt the coomal [possum], for where there are mungite in flower, there are always plenty of coomal.’ (Hassell 1975: 109,

Hassell does not attempt to name the species but describes how it was traded inland from the coast:

‘a species of banksia which grows near deep creeks and also on the sea coast… When they are in flower they look like beautiful round golden brushes, the flowers are about four inches long and composed of slender thread like stems. The podless ones have the longer blossoms. At the base of the flowers there are quantities of honey, the best honey is the podless ones, also it is the easiest to suck. This one is traded by the coast natives to the natives in the interior, for the honey keeps well for about a week. The birds and ants are also fond of this honey plant…. (Hassell 1975: 108)

The mythological story describes how Degindie’s wife collects mungite cones and puts them into her coot (bag) to carry home but while en route across the coastal plains, she and her husband, his two sons and her children are swept up into the sky in strong wind gusts, as punishment for letting strangers into their camp, where they can be seen at night during the Banksia season as forming part of Orion’s Belt and the Pleiades (jindie, chindie, stars). (Hassell and Davidson 1934: 236-238; Hassell 1975: 108-110; ).

Bool-galla, bulgalla, boolkalla – plenty of fire sticks

Another Noongar name for Banksia is bool-galla, usually attributed to Banksia grandis (see Grey 1840: 140 and Moore 1842: 21). Moore spells it bulgalla and describes it as:

‘The large-leaved Banksia, which bears the Metjo, or large cone used for fires.’ (Moore 1842: 21)

Drummond, on the other hand, records mangite as the name for Banksia grandis while the linguist Von Brandenstein (1979: 166) records piarar as the name for both B. grandis and B. attenuata. There is much confusion and inconsistency in the literature when it comes to assigning Noongar names to Linnaean-defined species. As we’ve already pointed out Noongar plant taxonomy did not follow a Linnaean speciation model. Rather the indigenous “names” reflected practical, utilitarian, seasonal, mythological or totemic “descriptors’ enabling easy identification in a culturally relevant way.

Plants often have more than one name depending on what aspect or function of the plant or plant product is being described and at what season (Macintyre and Dobson 2009 unpublished field notes).

The Banksia has a number of descriptor names depending on which of its products is being referred to, at what season and for what purpose. For example, mangite and bool-galla describe two different usages of the Banksia cones: Mangite refers to the nectar-laden flowers and the sweet nectareous beverage made by steeping it in water during the “mun-gyte backan-een” (mungyte – eating season, Grey 1840: 71) whereas Bool-galla literally translates as ‘plenty fire’ (bool, plenty + kalla, fire), ‘lots of fire,’ ‘many fires’ ‘or ‘the tree of many fires’ or as one senior Noongar Elder once described it to us as ‘the fuel tree.’ Dried Banksia cones (beara kalla) and bark (djanni) were a readily available and plentiful source of fuel, tinder and warmth throughout the year. They were also sometimes used as torches at night, as were the dried flower stems of the balga (grass tree, Xanthorrhoea). In 1834 Von Huegel (in Clark 1994: 37) observed that the Noongar always carried fire with them:

‘a large number of Aborigines walking through Perth to collect their daily ration at a particular spot near Mount Eliza’. He notes ‘The men never walk abroad without their spears, the women never without carrying some fire, for fire-making is a long and arduous task for them.’

Ignited Banksia bark (djanni) and cones were commonly used as portable fire sticks by Noongar people as a source of light and warmth and a ready means of igniting their campfires when moving around their country. In the cooler months the fire sticks or “kalla matta” (fire leg, walking fire) were carried under their bwokkas (kangaroo skin cloaks) as a portable source of body warmth.

Grey (1841: 267) writes:

‘In general each woman carries a lighted fire stick, or brand, under her cloak and in her hand.’

Moore (1842) stresses the importance of the lighted djanni (Banksia bark):

‘In cold weather, every native, male or female, may be seen carrying a piece of lighted bark, which burns like touch-wood, under their cloaks, and with which, and a few withered leaves and dry sticks, a fire, if required, is soon kindled. A great part of the fires that takes place in the country arise from this practice of carrying about lighted Djanni. In the valleys, even in summer, the air is chill before sunrise.’ (Moore 1842:20)

The large cones of the Bull Banksia (Banksia grandis) were favoured. Nind (1831 in Green 1979: 21) observed in the Albany area that:

‘Every individual of the tribe, when travelling or going to a distance from their encampment, carries a fire-stick, for the purpose of kindling fires, and in winter they are scarcely ever without one under their cloaks, for the sake of heat. It is generally a cone of Banksia grandis, which has the property of keeping ignited for a considerable time. Rotten bark, or touchwood, is also used for the same purpose. They are very careful to preserve this, and will even kindle a fire (by friction, or otherwise) expressly to revive it.’

In 1834 Collie describes how Manyat, his Aboriginal guide for the King George Sound area, used different types of Banksia cones for carrying and producing fire:

‘On him [Manyat] devolved the office of fireman – not for extinguishing, but for carrying and lighting up. This he did with the barren spikes of the banksia serrata *(or mungat), the seeded cones of the banksia grandis, or the bark of the mahogany eucalyptus. The first and last require no preparation, but the second is made to undergo torrefaction, by being placed in the fire till the outer surface be a little burnt, is then buried in a hole scraped in the earth with the pointed handle of the native knife (taap), or the tomahawk (koit).’ (Collie 1834 in Green 1979: 94).9

Collie explains that the cone of Banksia grandis – before it can be used – must be lightly burned and then scraped with the pointed wooden end of the native knife or axe to expose a tinder-like fluff that was easy to ignite and would slowly burn.

Hassell also refers to this process of preparing the Banksia spike. She notes that the grey brown outer-covering was scratched with the finger nails (or knife, taap) to release or expose the fluffy velvety flammable material underneath. She states:

‘on being sharply rubbed the grey outside covering comes off leaving a beautiful dark brown velvety stuff which if scraped reveals a hard stick about half an inch thick. The early settlers used this velvety stuff for stuffing mattresses and pillows, when they could not get palm wool’ (1975:107-108).

Banksia cones of all sizes were used, depending on what was available. The smaller cone of the narrow-leaved Banksia, according to Moore (1842: 14) was called birytch:

‘It burns like touchwood. One is generally carried ignited by the women in summer, as pieces of burning bark are in winter, to make a fire.‘

Grey (1840: 10) describes berytche as the

‘small cone of the Banksia, somewhat resembling Met-jo: it burns slowly, like a pastil.’

The importance of biryt (light) in its different manifestations as firelight, daylight or sunlight is discussed in our paper where we describe how Nanga the sun woman in Noongar mythology was believed to be the original bringer of light, fire and warmth to the world, see here.

‘Every day from sunrise to sunset she can be seen walking across the sky carrying her burning fire stick. This is a lighted Banksia cone known as birytch – its meaning deriving from beerat or biryt meaning ‘light’ or ‘daylight’. As a descriptor birytch alludes to the light emanating from the burning Banksia cone carried by Nanga in the sky or light-emanating Banksia cones carried by her earthly descendants who carried a smouldering Banksia cone when moving camp or travelling anywhere. This portable fire-stick was also referred to as “kalla matta” (literally, kalla, fire and matta, leg or ‘fire leg,’ see Moore 1842: 39). This translates into the colourful indigenous metaphor of ‘walking fire.’ (Macintyre and Dobson 2017)

The early European settlers soon took advantage of Banksia cones for fuelling their winter fires. One advertisement for firewood in the Albany Advertiser on June 23 1890 stated “Mungite nuts always on hand.” Ethel Hassell (1975: 108) also emphasises the usefulness of Banksia cones for fire purposes:

‘greatly used for fires; a few placed together will smoulder on the hearth all night, giving a pleasant heat.’

Some other uses of Banksia

The Banksia bark was also used as an abrasive. Moore (1842: 20) describes how they used the bark as a type of sandpaper for the production of artefacts. For example, after charring the end of the wanna (digging stick) or dowak (throwing stick) in the fire, it was then ‘rasped to a point with the Djanni.’

Noongar Elders informed us that the Banksia plant was also used as a source of medicine. They said that the bark (djanni) that was used for firewood was clean burning and did not spark. The ash was white and fine and when mixed with the resin of the marri tree was used as a medicine for curing stomach conditions, especially diarrhoea and the control of intestinal worms.10

One of the Elders said that sometimes the young green buds on the smaller species of Banksia were chewed in early spring. He said they were ‘not unpleasant tasting when young’. He commented that it was a “chewing gum” to the Noongars and was used as a digestive and also a hunger and thirst suppressant. He demonstrated how it was used by breaking off a tender bud and chewing it.

Two Elders referred to the ‘old people’ collecting edible grubs from under the bark and in the fruit of Banksia. We could not determine which grubs they were referring to but, according to Hammond (1933), the larvae from the Banksia were considered the least palatable of all, tasting rather woody.

Conclusion

The mungyte season was the time of ‘coming together’ for ceremony and celebration. It was the time of Banksia flowering, parrot breeding and the de-pouching of young kangaroos. Grey (1840: 71) records ‘kum-bar-ung as:

‘the season which follows “jilba,” and is followed by that of “Berok,” (about October) “Mun-gyte backan-een,” the mungyte eating season.’

We would suggest that the “named period” of Kumbarung (as it is spelt by Grey 1840: 71 or kambarang, Moore 1842) probably derives from kumbar (or coombar, cumbar) meaning ‘big’ or ‘large’ referring to the large number of people coming together at this time of the year for social, ceremonial and economic purposes. The mungyte eating season was a time for celebration and communal hunting pursuits (e.g. kangaroo hunts) were carried out. These spring gatherings included the mant or mandjar – the ritual exchange of cultural items – and the creation and renewal of social and political alliances.

As far as we are aware, the nutritional value of local southwestern Australian Banksia nectar has never been tested. Using traditional ecological knowledge and the involvement of Noongar people, it would be useful to ascertain the nectar’s beneficial properties. To this day Noongar traditional foods, such as Typha rhizomes, Acacia gum and seed, Banksia nectar and others have been scientifically overlooked as to their unique nutritional and potentially medicinal qualities. They are regarded as “bush tucker” but there has been negligible research conducted by our universities or government departments into the chemistry of these traditional foods.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper is based on extensive archival research together with information gained from fieldwork and consultations involving Noongar Elders from the Perth, Pinjarra, Busselton and Albany regions. We would like to thank all Noongar Elders (past and present) who have contributed to this work.

ANNOTATIONS

- There are numerous ways of rendering Noongar sounds and words into the written language. Often “oo” equates to “u.” For example, Noongar is also spelt as Nyoongar, Nyungar or Nyungah, depending on an individual writer or group’s orthographic preference. Most Noongar terms have numerous variant spellings, depending on regional linguistic variations or different orthographies and phonetics adopted by the different recorders. Mangite is also rendered as mungite, mangyt, mungyte, mangitch, mangaitch, mungitch and ngok as ngug, ngook etc. Wilf Douglas, a Nyungar language specialist, records ngug as ‘honey’ (1979: 70) and similarly Rosemary Whitehurst (1992: 21) a Nyoongar linguist, as noted in our paper, records ngook as honey. The taste of sweetness is also known in Noongar as ‘koort-boola’ (literally, ‘lots of heart’, ‘plenty of heart’) or ‘koort kwobba’ = ‘heart happy’, it makes one happy. The Noongar language contains many compound words that have metaphorically colourful meanings as already noted in our paper on daylight reckoning, namely the metaphorical expressions for ‘sun down’ and ‘sun set,’ see http://anthropologyfromtheshed.com/project/light-time-traditional-noongar-culture/

- Indicator birds were often used to signal the readiness and ripeness of indigenous foods for harvest. For example the “by-yu bird” announced when the oil-rich red seeds of Macrozamia (by-yu) were ripe and ready for collecting by Noongar women. This was usually late February/ March depending on localised weather patterns and seasonality. The by-yu was processed, stored and consumed in April/May during the season of jeran. See our paper http://anthropologyfromtheshed.com/project/macrozamia-sarcotesta/ Fermentation was practised by Noongar people not only in the processing of by-yu but also in the steeping or brewing of the nectar-laden Banksia flowers into a mild intoxicant as described by Daisy Bates, Roth and contemporary Noongar Elder informants.

Grey (1840: 29, 33, 102) records:

djil-yoor ‘a species of mouse that burrows in the ground, eaten by the natives.’

dtor-dung a species of mouse eaten by the natives at King George Sound.

mardo – a species of mouse;

mun-dar-da – a small species of mouse, which is generally found in the tops of Xanthorrhoea.

ngool-boon-goor (K.G.S.) – a species of mouse eaten by the natives;

nu-jee – a large species of mouse that burrows in the earth, and is eaten by the natives.

- Moore (1842: 146-147) records the same names (albeit spelt slightly differently) :

Mouse, small burrowing kind, eaten by the natives – Djil-yur

Mouse, species of – Mardo; Ngulbungur.

Mouse, small species – Mandarda.

Mouse, large, eaten by the natives – Nuji; N-yuti (Upper Swan)

Mouse, small species, supposed to be marsupial – Djirdowin.

- The dibbler, a small carnivorous marsupial with distinctive white eye rings, was thought to have been extinct, until it was rediscovered near Albany in the 1960’s by naturalist and author Michael Morcombe. It not only eats insects and nectar from the Banksia but being carnivorous it feeds on honey possums, bush rats and other small animals which feed at night-time and at dawn on Banksia flowers, such as B. attenuata and B. grandis. The nectarivorous flowers of many plants including Banksia, Grevillea, Hakea, Calothamnus, Callistemon, Jarrah, Melaleuca and Marri were animal and bird attractants at different times of the year.

- The Noongar were resourceful in conserving their energy while hunting; for example, during the Banksia nectar-collecting they would exploit bird and animal competitors to obtain a rich supply of fat and protein.

- It is extremely difficult to decipher Barker’s handwriting. We’ve noticed that his r is easily mistaken for n. For example, Mulvaney and Green (1992) transcribe the name of the cold wet season as moken but on careful analysis this may be interpreted as moker which is consistent with Nind’s (1831) rendering of mawkur and Collie’s (1834) mokkar.

- We found mondyit recorded as referring to ‘rosella’ in Hassell’s undated (probably 1880’s-1890’s) handwritten unpublished notes in the Rare Books section of the Battye LIbrary. We subsequently noticed the term mondyit listed in Bindon and Chadwick (2011:160) as rosella.

- It is unclear why Abbott (1985: 7-8) lists Moore’s budjan as Dryandra sessilis when Moore (1842:19) records budjan as “Dryandra Fraseri – a shrub.” Whether this is an oversight on Abbott’s part or based on his own re-interpretation of Moore’s work is unclear. The same indigenous name budjan probably applies to both shrubs D. nivea and D. fraseri as they both contain sought- after “nectar pots.”

- The species known as Banksia serrata is not found in Western Australia. It is unclear to which species Collie (1834) is referring here.

- It was suggested by an Elder that the ash of Banksia has an anti-septic quality and when it is mixed with emu fat and leaves it makes a healing balm.

BIBILOGRAPHY

In progress

National Museum of Australia Plate 25: “Kalga – Honey gathering hook.”

This was used by Noongar people to pull down the nectar- laden banksia flowers.

APPENDIX 1:

Glossary – Nyungar terminology relating to Banksia cones & seed vessels

‘Beera – ‘Banksia grandis’ (Lyon 1833 in Green 1979: 171)

Bool-galla – the Banksia grandis’ (Grey 1840: 14)

‘Bulgalla – The large-leaved Banksia, which bears the Metjo, or large cone used for fires.’ (Moore 1842: 15)

Me-tjo – the seed vessel of the Eucalyptus, the cone of the Banksia (Grey 1840:83)

Metjo – ‘the seed cone of the Banksia’ [Moore (1842: 52) also lists metjo as ‘the seed-vessel of the Gardan, red gum.’ [ Are Grey & Moore confusing the Banksia and red gum or is the term ‘metjo’ generic and applicable across Genus type, that is, the seed-vessel of the red gum is lumped together with the seed cone of the Banksia]

Me-tjo-nu-ba -‘the seed vessel of the cone of the Banksia’ (Grey 1840: 83) [presumably referring to the young seeds inside the banksia cone, which when mature are released]

Metjo-nuba – ‘The seed-vessel in the cone of the Banksia.’ (Moore 1842: 52) [as above, nuba = the young of anything, in this case young seeds]

Me-tjo-koon-dail – ‘the inner seed vessel of the Banksia cone.’ (Grey 1840: 83)

Metjo-kun-dyle -‘The inner seed vessel of the Banksia cone. The seed itself.’ (Moore 1842: 52)

(Moore 1842: 45 records kundyl as having a number of meanings including ‘the seed of any plant; the interior of the zamia plant; young grass springing after the country has been burned; anything very young still growing; the soft inside of anything…’)

APPENDIX 2:

Pygmy Possum – The West Australian 10-12-2014