Report on the “Owl stone” Aboriginal site at Red Hill, northeast of Perth

Ken Macintyre and Barbara Dobson

Overview

Consulting anthropologists Ken Macintyre and Dr Barbara Dobson were invited by members of the Combined Swan River and Swan Coastal Plains and Darling Ranges Nyungar Elders, Native Title Holders and Traditional Owners (CSR & SCP) to investigate and record a prominent standing stone (“owl stone”) on Hanson’s Lot 11 as the Elders were concerned that this was of cultural significance to them and had not been recorded at the Department of Indigenous Affairs (DIA). The Elders asked the anthropologists Ken Macintye and Dr Barbara Dobson to assist them to record the ‘standing stone’ site to ensure its protection under the Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972.

This site investigation was undertaken on 16th October 2008 in the company of senior Elders Albert Corunna, Greg Garlett and Bella Bropho (on behalf of Robert Bropho). Richard Wilkes, who was unable to attend the site visit, was consulted by telephone. Others present at the site investigation were Arpad Kalotas (Regional Officer, DIA, Midland); Margaret Jeffery (Recorder for the Swan Valley Nyungah Community); Cliff Kelly (Red Hill Quarry Manager) and Hans Georgi (Quarry Foreman) from Hanson Construction Materials Pty Ltd (referred to as “Hanson’s” in this paper) and consulting anthropologists Ken Macintyre and Dr Barbara Dobson.

It should be highlighted that neither the anthropologists nor the Nyungar Elders and Traditional Owners received any remuneration for their services either from the company (Hanson Construction Materials Pty Ltd.) or from any other source. The site visit and recording was conducted voluntarily in order to ensure that the site was properly recorded and protected from quarrying and blasting activities.

The investigation conducted by Macintyre and Dobson in the company of the Nyungar Elders and Traditional Owners was not an ethnographic field survey per se but rather a visitation to a specific site on Lot 11 comprising a prominent standing stone (“owl stone” which featured three remarkably balanced stones), which the senior Elders wanted recorded as a place of cultural significance.

As a result of these consultations, site visit and archival research, it was concluded that the prominent “owl stone” at Hanson’s Lot 11, Toodyay Road, known to the Elders as Boyay Gogomat, was of high cultural and spiritual significance to them.

The standing stone was perceived to be a symbolic representation of the ancestral hawk owl, probably the Southern Boobook Owl (Ninox novaeseelandiae). The Nyungar Elders and Traditional Owners believed that this ancient “owl stone” was a culturally important, spiritual and totemic site which must be respected and protected at all times, or else it could be dangerous. (See under 5.0 Conclusion and 6.0 Recommendations).

It should be highlighted that only the standing stone (“owl stone”) was investigated by the anthropologists. No other sites were visited or investigated. It is possible that other sites of potential Aboriginal significance may be located within Hanson’s Lot 11.

The anthropologists strongly recommend that a thorough Aboriginal heritage survey be conducted over the entire area of Lot 11 to ensure that if any other sites of significance exist, that these are recorded in accordance with the Act.

For information on the significance of owls and other night birds in traditional and contemporary Nyungar culture, see Appendix 9.8. This research paper provides an overall context and insight into the nature and complexity of Nyungar views on owls and may help the reader to better understand the occurrence and significance of “owl stones” in Nyungar culture.

‘Aboriginal culture and tradition is inseparable from the land. When land and its natural features are destroyed, a large part of Aboriginal history and culture is destroyed. The reality is that not only are Aboriginal people losing their physical space but they are losing the physical manifestations of their history, culture and identity – and they have no voice. Who can they appeal to?’ (Macintyre and Dobson 1999).

UPDATE – Since writing the Owl Stone report in March 2009 (and this report has been publicly available since April 2009) the “Owl Stone” has been registered at the Department of Indigenous Affairs as a site of high significance to Aboriginal people. Although “protected” under the Aboriginal Heritage Act it is still highly vulnerable to daily vibrations caused by constant blasting and quarrying activities. This prominent standing stone site is located within a larger site complex which includes ochre quarries, petroglyphs, water sources, other mythological sites and archaeologically verified grinding stones unique to the Darling Scarp. The site known as the Red Hill camp (site ID 27113) that was officially registered as an Aboriginal site of archaeological significance in 2008/2009 has since been de-registered by the Dept of Aboriginal Affairs and is soon to be destroyed by hard rock quarrying. This has been the fate of numerous Aboriginal sites as our State values mining and quarrying activities above Aboriginal heritage and history.

Contemporary Nyungar views on the “Owl Stone”

(Based on consultations with Nyungar Elders/ Traditional Owners in Oct-Nov 2008)

The Elders views are presented here verbatim in order to convey their true feelings and concerns about the “owl stone” site at Red Hill which they wanted recorded and registered at the Department of Indigenous Affairs as a site of spiritual and cultural significance to them.

‘Why is it that the wadjela [white man] wants us to prove that our Ancestors lived on this land, had ceremonies and made this land live for thousands of years. We know their story – it’s written all over this land. You wadjelas can’t see it ‘cause all you can see is the money you’re going to make from our Spiritual Dreaming.’

‘It’s such a spiritual place to us. We don’t know how to explain it whitefella way, you just feel it all over your body and you know that ‘the old people’ are here.’

‘We knew before we saw it that there was something waiting for us. We could feel it.’

‘The Standing Stone has been there since the beginning of time.’

‘I am part of the Spiritual Dreaming when it begun.’

‘This place is important to us. You can feel it all around. We knew it was here because we saw the engravings over there at Boral’s. They were pointing over here. We knew it was pointing to something really important.’

‘There will be other “pointers” all up the valley to mark the way for the ‘old fellas’ coming down from the east. All along the old trails there would be markers for this one and other places of importance along the way.’

‘When I first saw the stones, it felt like I had found something which had been lost. It was like I had found a piece of a jigsaw that had been missing. You know the feeling you get when you find something that once belonged to you’.

‘This is a very important site to our ancestors here. You can feel ‘the old people’ walking around here.’

‘It’s like an older brother, this stone. It will not harm you but will protect you from danger as long as you respect him. I feel really calm here.’

‘These old sites are not lost. They’re being looked after by ‘the old people’ [ancestors] who have been waiting for us to come and take over from them. If I close my eyes, I can see ‘the old people’ sitting down smiling at us, happy that we’re here.’

‘You gotta record this place for the Nyungar people. It’s a big place for heritage and culture.’

‘That old owl is sitting there watching everything. That bird can see a long way and knows everything that happens.’

‘That owl has been there for thousands of years and now it’s just sitting there everyday watching the quarry getting closer and closer.’

‘If there is blasting or machine movements anywhere near there the vibrations of that Ground could unsettle what Nature has allowed to stand there all these years since the Beginning of Time.’

‘The underground vibrations of when they started blasting could unsettle the Stone standing there. It could fall and be destroyed forever.’

‘The standing stone is not like a seed of a plant or a tree that you could replant. It must be protected.’

‘Our sacred sites have been there forever. What gives a white man the right to destroy something so old and sacred.’

‘That old owl is a living stone to us. We can feel its spirit giving life.’

‘Can’t you feel the sacredness of that stone. You don’t need to touch it; just being near it is enough.’

‘That stone is so spiritual that it talks to me in my sleep.’

‘Whitefellas have destroyed our Bible and now they want to crush the last stone of our cathedral.’

1.0 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background to site visit

Consulting anthropologists Ken Macintyre and Dr Barbara Dobson were invited by members of the Combined Swan River and Swan Coastal Plains and Darling Ranges Nyungar Elders, Native Title Holders and Traditional Owners (referred to subsequently in this report as “the Nyungar Elders and Traditional Owners” or for brevity purposes simply abbreviated to “the Elders”) to accompany them to investigate and record the remarkable standing stone at Hanson’s Red Hill quarry project area (Lot 11, Toodyay Road, City of Swan) which they believed to be of cultural significance to them, and which had not been previously recorded.

This site investigation of the standing stone was undertaken by anthropologists Macintyre and Dobson on 16th October 2008 in the company of Nyungar Elders and Traditional Owners for the Perth and Darling Range region; together with a Department of Indigenous Affairs (DIA) representative Arpard Kalotas, and Hanson’s Red Hill Quarry representatives Mr Cliff Kelly (Quarry Manager) and Hans Georgi (Quarry foreman).

It should be highlighted that neither the anthropologists nor the Nyungar Elders and Traditional Owners received any remuneration for their services either from the company (Hanson) or from any other source. The site visit and recording was conducted voluntarily in order to ensure that the standing stone site was properly recorded and protected from quarrying and blasting activities. No other sites within Lot 11 were visited or recorded by Macintyre and Dobson owing to the fact that this was not an ethnographic field survey per se but rather a visitation to a specific site comprising a prominent standing stone (“owl stone”) which the Elders wanted recorded as a place of cultural and spiritual significance to them.

For some years the Elders had been corresponding with the DIA, City of Swan and other authorities requesting that they be involved in a proper Aboriginal heritage survey of Hanson’s current and proposed quarry expansion areas to ensure that no sites of significance to them are impacted by the quarrying and blasting activities. However, despite the Elders continued efforts, no ethnographic survey was arranged, so out of concern for the site, they asked anthropologists Macintyre and Dobson to assist them to record the prominent balancing stone known to them as Boyay Gogomat or “owl stone.”

1.2 Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Hanson Construction Materials Pty Ltd representatives, Mr Cliff Kelly (Quarry Manager, Red Hill) and Hans Georgi (Quarry Foreman, Red Hill) for accompanying and guiding the site investigation team to the “owl stone” to enable it to be photographed and recorded.

We would like to acknowledge the assistance provided by the following members of the Combined Swan River and Swan Coastal Plains and Darling Ranges Nyungar Elders and Native Title Holders and Traditional Owners (CSR & SCP), namely, senior Elders Albert Corunna, Greg Garlett, Bella Bropho and Richard Wilkes for showing the researchers the “owl stone” site and sharing their personal views on the significance of owls and “owl stones” in Nyungar culture.

Finally, we would like to thank Birds Australia for the photographic images of birds provided by arrangement with Birds Australia Western Australia. A special thanks to the photographers Rod Smith, Tony Brown, Victoria Bilney and Debbie Walker, members of Birds Australia, for their photos of boobook owls and tawny frogmouths used to illustrate our text.

1.3 Methodology

The site investigation and recording process involved seven phases:

(i) A pre-site meeting at Hanson’s office (Red Hill quarry) with Nyungar Elders, Native Title Holders and Traditional Owners for the Perth and Darling Range area in the presence of Arpad Kalotas (Regional Officer, Department of Indigenous Affairs, Midland); two representatives from Hanson Construction Materials Pty Ltd, Cliff Kelly (Quarry Manager) and Hans Georgi (Quarry Foreman), and consulting anthropologists Ken Macintyre and Dr Barbara Dobson from Macintyre Dobson and Associates Pty Ltd.

(ii) a site visit and investigation of ‘the standing stone’

(iii) a post-site meeting at Hanson’s office to inspect Company maps in order to precisely locate ‘the standing stone’ in relation to current and proposed works;

(iv) historical research relating to the upper Susannah Brook area

(v) ethnohistorical research on the significance of owls in Nyungar culture,

(vi) subsequent consultations with the Nyungar Elders to collect further information on owls and owl stones in Nyungar culture,

(vii) recording the site in accordance with the requirements of the Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972.

The site recording forms complete with photos and attachments were lodged by anthropologists Macintyre and Dobson with the Department of Indigenous Affairs on 3rd December 2008. The site was officially listed on the DIA sites register on 4th December 2008 as site ID 26057 known as the Ancestral Owl Stone (Ceremonial, Mythological).

However, on 23rd December 2008 the (internal) DIA Site Assessment Group for some reason determined that the status of the “ancestral owl stone” site was IR meaning “insufficient information”, despite 10 pages of text and photos provided to DIA together with the “owl stone” site recording form. According to recent advice from the DIA, this IR classification means that the status of the site is “in limbo”, meaning that it is not currently recognised as a site, nor is it ‘not a site’, nor is it recommended to the ACMC that this site be listed on the permanent register (PR).

For what reason the Site Assessment Group has assigned this important site to the status of IR (Insufficient Information), and not to the PR (Permanent Register) in view of its mythological, ceremonial, totemic and spiritual significance to Nyungar Elders is unclear. It is also unclear why the DIA did not notify the anthropologists Macintyre and Dobson or the Nyungar Elders who assisted in the site recording to (i) advise them about the site’s “Insufficient Information” classification, or (ii) to ask for further information about the site. It was made clear in the site recording papers that a full report was being prepared by Macintyre and Dobson for the Nyungar Elders on the cultural significance of this “owl stone” site.

According to the Aboriginal Heritage Inquiry System:

“Sites lodged with the Department are assessed under the direction of the Registrar of Aboriginal Sites. These are not to be considered the final assessment. Final assessment will be determined by the Aboriginal Cultural Material Committee (ACMC).”

The IR status of the Owl Stone Site is of great concern to the Nyungar Elders and Traditional Owners to whom this site holds a deep spiritual significance. In view of the site’s vulnerable location within Hanson’s proposed hard rock quarrying and blasting project area, it is hoped that this report provides “sufficient information” for the site to be added to the permanent register at DIA.

2.0 “OWL STONE” (RED HILL/ UPPER SUSANNAH BROOK)

2.1 Historical Background

There appears to be scant historical documentation relating to (what was once considered to be) the upper reaches of the Susannah Brook and the surrounding hill country in which the “owl stone” is located (see Figure 1 and Plate 4). Most historical information that is available on the river focuses on the lower reaches, extending from the base of the Darling Scarp to its confluence with the Swan River, where the rich alluvial soils were highly prized by the early settlers for agriculture and were among the first land grants taken up in the Swan River colony.

Archival research shows that the Susannah Brook first appeared as the “Susannah River” in an “eye sketch” map by J.S. Roe (Surveyor-general) in 1829 when the Swan River Colony was first founded.1 As early as 1827 Captain James Stirling and the New South Wales colonial botanist Charles Fraser explored the lower reaches of this river near to its confluence with the Swan River (Statham 2003: 76). Owing to the fact that the Susannah River was located mostly on Colonel Latour’s property (Swan Location 6), its alternative name in the 1830’s was Latour’s Brook. 2

Moore refers to Latour’s Brook as transecting his own grant at Swan Location 5a. He notes: ‘I find that the brook called Latour’s brook or Susannah river crosses my grant twice.’ (Moore 16th April 1833 in Cameron 2006: 221).

Moore (1832) describes his disappointment on discovering that the valley from which the Susannah river issues from the hills does not appear to fall within his grant:

‘I cleared with my own hands (and a good American axe) eleven hundred yards of a vista through the bush to my lower boundary line. I was in great hopes that a valley from which the Susannah river (Latour’s brook) issues from the hills was in my share but, on getting a view through the vista, fear that it is not. However, as the brook traverses my grant twice, it makes the whole land valuable. A sketch of it to shew situation and localities.’ (Moore 9th August 1832 in Cameron 2006: 138).

Moore (3rd May 1832) describes his first walk into the Susannah river valley as follows:

‘Went direct to the hills behind my place to the opening of a valley which I had heard of where Col Latour’s brook (as it is called) issues from the hills. It is a beautiful picturesque valley or glen of no great extent. We traced it up about 3 miles when it spread into different branches or rather several branches united there. No one branch appeared to be of any great extent so we turned back without exploring further, but in this we may be mistaken. These vallies frequently contract in some places & expand again in others more than you would expect; so I shall make another exploration at some other time. In some places the sides were very precipitous, formed of great masses and fragments of granite and whinstone – water in pools in some places but I do not think there would be water throughout the summer in any place I saw, though the water is running now in some places. …We saw the old huts of several natives, 11 in one place, 7 in another – bones, feathers and fur strewed all about.’ (Moore 1832 in Cameron 2006: 113)

Moore’s work provides the earliest historical reference to Aboriginal habitation in the upper reaches of the Susannah River valley. This is relevant as, to our knowledge, it is the only documented evidence. From Moore’s description, the large number of huts observed would suggest that some important social and/or ceremonial activities had taken place prior to his arrival. If this were the case, an area in close proximity to this habitation must necessarily have had some mythological significance and for such ceremonial occasions to take place, there must have been a plentiful supply of food and fresh water to sustain the large group (or groups) at this time of the year.

There is no reference in the general ethno-historical or anthropological literature to the Nyungar name for what is now known as the Susannah Brook. However, recently acquired information by Macintyre and Dobson (2008) reveals an interesting discovery – that the original Nyungar name for the head of Susannah Brook (that is, the ‘head’ as located in 1836) and the surrounding hill country was Goolgoil – which based on our research may be translated as ‘owl.’3 (see Appendix 9.1).

Drummond’s (1836, 1839) goolgoil may be viewed as a different phonetic rendering of Moore’s (1835, 1836) gogo (or gurgur, goorgoor) which is the Nyungar onomatopoeic name for the owl, most probably the Southern Boobook (Ninox novaeseelandiae).4 The question of whether the upper part of the brook and surrounding hill country which is traditionally known as Goolgoil traditionally derived its name from its association with Gogomat, the powerful ancestral owl who is believed to have metamorphosed into stone at Boyay Gogomat on the hillside overlooking the Susannah Brook, can only be conjectured.

The whole extent of the Susannah Brook watercourse, excluding its tributaries, is a registered Aboriginal heritage site (ID 640) with mythological and cultural significance. It is listed on the permanent sites register at the Department of Indigenous Affairs. However, during post-survey consultations regarding the “owl stone” the senior most Elder pointed out to Macintyre and Dobson that the tributaries of the Susannah Brook are also of cultural significance to Nyungar people. He stated:

‘All the feeders into the brook are part of the river system and the Waugal was the one who created them all. I can’t understand how the Sites Department can make that brook a site but not its feeders. Without the feeders there would be no brook. The Waugal visits all of them – that’s his run’

McDonald Hales and Associates (1990) recorded a site known as ‘the Susannah Brook Waugal” (site ID 3656) which is a pool located in the Susannah Brook, said to be located just outside and west of Lot 11. However, for some unknown reason the details of this site (including the site coordinates, site boundaries and associated map) are classified by the Department of Indigenous Affairs (DIA) as “closed,” hence the information is restricted and cannot be accessed without permission from the original recorders.

Without access to these site coordinates and further field investigations with the Nyungar Elders and Traditional Owners, it is impossible to ascertain whether this Waugal pool site (ID 3656) is one of the ‘fine springs of water at the foot of the hills at Goolgoil…’ referred to by Drummond (1836) (see Appendix 9.1) and/or whether ID 3656 is one of the pools referred to by Moore (1832 in Cameron 2006: 113) when he walked about 3 miles up the Susannah Brook Valley to what he thought were the headwaters.

Drummond (1839) refers to the “watering place” known as Goolgoil as being located to the west of the hill through which the (old) Toodyay Road passes. When this information is added to his 1836 description of Goolgoil as being located at the head of the Susannah Brook (including the adjacent hill country) and Moore’s observation of pools when he journeyed 3 miles journey upriver to what he considered to be the headwaters of the brook, this would appear to locate Goolgoil within or in close proximity to Hanson’s Lot 11. It should be pointed out that as with many traditional Nyungar place names these often denoted a locale consisting of several related topographic features rather than a single specific feature. This helps to explain why adjacent hills, ridges and water sources sometimes were known by the same name. It may be conjectured that the powerful “owl stone” which marks an important site along the “track” (mat) of Gogomat, the Ancestral Owl Being, gave its name to the locale.

It is possible that the Susannah Brook Waugal site (ID 3656) is one of the pools referred to by Moore (1832) and/or one of the springs referred to by Drummond (1836) and may fall within the stretch of the upper Susannah Brook Valley known traditionally as Goolgoil which included a known “watering place” (1839) to Aborigines. These sites may also have been connected to the “owl stone” site overlooking the Susannah Brook.

Macintyre and Dobson (1993, field notes relating to the Pinjarra-Murray region) recorded part of a myth from a Nyungar Elder who stated that there is a close relationship between the mopoke (what he called Gambigur) and the carpet snake (Wakaal). The story, according to the informant, related to the custom of sharing meat, for the Wakaal and the owl were like brothers. They both hunted at night and would share their meat with one another. However, one night the mopoke was unsuccessful and did not catch anything, so he went to the carpet snake’s camp and saw him finishing off the last of the meat (dadja) which he had caught. The mopoke became very angry at the Wakaal for not sharing his food and attacked him with his club. They fought all night until daybreak. The mopoke became blinded by the sunlight and at this time the Wakaal escaped into the river and sank to the bottom creating a large pool. The mopoke flew onto a large tree overlooking the pool, waiting for the Wakaal to come out. However, the Wakaal never came out but made tributaries up and down the river to enable it to move around in search of meat.

The Nyungar informant only knew this small fragment of the story and did not know which part of the country the story originated from. He said he had heard ‘old people’ talking when he was a child.

During post survey consultations to review the draft report, we were informed by the Nyungar Elders that this myth of the owl and the Waugal was known to them and could have application to the Red Hill area as it does to other parts of Nyungar country. They stated that such stories did not necessarily apply only to one place but were a recurring theme in southwestern Australia.

Interestingly, Bates (in White 1985: 219) identifies “the owl or mopoke” together with the Woggal and the eaglehawk as the three most supreme, almost deity-like, mythological Ancestral Beings in Nyungar religion. She states:

‘The Perth natives believed that the mopoke had power to punish them if they broke certain native laws. He was said to have changed the eaglehawk, the crow, the white cockatoo and the emu into men and women.’

These powers attributed to the ancestral owl are indeed significant. They not only help to explain the significance of the “owl stone” at Red Hill as symbolizing a highly significant totemic being in Nyungar religion, but they may also help to explain why the Owl/ Waugal story is said by contemporary Nyungar Elders to recur throughout the south west region. The owl is an iconic totemic being which features strongly, not only in Nyungar culture, but also in the foundation myths of other Aboriginal cultures. 9, 10

Just as the Waugal “can be controlled by certain medicine men” (Bates in White 1985: 219) , so too can the owl or mopoke, which, as shown in this report, is often associated with the powerful bulya men (sorcerers) as their “assistant totems” (see Appendix 9.84).

Thus, the Waugal and the mopoke not only represent the highest echelons of Nyungar totemic mythology, but both are powerful creators, healers and destroyers, and it is for this reason that their ancestral and “living” spirit beings must be protected at all times. They are both arbiters of life and death, and mete out punishment to those who violate customary law.

Both are associated with sacred winnaitch areas which require the performance of certain ritual ceremonies (such as the strewing of rushes in accordance with tradition) to avoid harmful consequences to those passing by. Bates collected numerous anecdotes relating to this ritual, most notably in places associated with the mythical Waugal:

‘the power of the sacred snake to punish those who transgress its rules at various places. In consequence these places were either strictly avoided or a special propitiatory offering was made by those who camped or hunted nearby’ (in White 1985: 220).

Similar ritual propitiations applied to the owl stone (Gogomat). George Fletcher Moore (1835) observed his Aboriginal guides conducting with utmost seriousness and ceremony the respectful ritual of strewing Xanthorrhea leaves around the base of the stone at Boyay Gogomat in the Lower Chittering. Similar rituals were (and still are) carried out by contemporary senior Nyungar Elders and Traditional Owners when visiting the “owl stone” at Red Hill in keeping with how they carry out customary rituals associated with such sacred places.

Both the Waugal and the Owl (Gogomat) were important guardian spirits associated with winnaitch areas. Is it a coincidence that both of these supreme Totemic Beings are to be found in close proximity to one another at Red Hill?

According to O’Connor, Bodney and Little (1985: 106) the whole of the Red Hill area is considered winnaitch:

‘The entire Red Hill region is a winnaitch area: avoided in traditional times because of the existence there of Wurdaatji [also Wudjaardi], spirits who live in the jarrah forests and who assume a small human-like form and can be dangerous to humans if aroused. Although Aboriginal woodcutters worked right through the area in historical times, they were people of the coastal plains and earned their living under constant fear of the Wurdaatji….[these fears] are understandable and very real. The researchers were told by a number of sometime-woodcutters of humans and dogs being subjected to constant surveillance by Wurdaatji; of dogs being killed at night; and of woodcutters’ camps being subjected to barrages of abuse, stones and even large rocks at night.’

The stories related here by O’Connor, Bodney and Little (1985) which regard the whole of the Red Hill area as winnaitch and perceived to be associated with woodatji (or woodarchi, wurdaatji) and other guardian (often malevolent) spirits is indeed significant from an anthropological viewpoint. It was not uncommon for Aboriginal groups who had resources and/or sacred totemic places to protect, to generate stories and symbols to keep outsiders away.

Even natural symbols such as the owl stone would have generated fear to those who did not understand the local rituals and ceremonies for the place. In this context, the term winnaitch does not only refer to the dread of woodarchi and dangerous spirits, but in traditional times also indicated a place of high totemic significance and sacredness – an area to be avoided by outsiders and the uninitiated. The woodarchi and other malevolent spirits were indeed protectors of such places and served to keep strangers out.

The term winnaitch, as applied to the Red Hill area, has in some contexts been misinterpreted by anthropologists to mean total avoidance, implying that people avoided the place out of fear of malevolent supernatural agents. This may have indeed been the case for the coastal lowlanders who, when travelling or working in the area, viewed it with the utmost fear (as noted above by O’Connor et al. 1985), However, to those people who owned, belonged to and inhabited the hill country (referred to by the coastal lowlanders as Boyangoora which literally means “stone camps” or “Hill people” (see Tommy Bimbar 1916), the woodarchi and winnaitch constituted an effective social and territorial control mechanism to keep intruders away from their sacred sites (totemic, ceremonial, ritual and mythological) as well as their habitational, stone and ochre quarry places.

It was believed that people who did not respect these winnaitch areas, and who did not perform the proper rituals when passing, could die. It was for this reason that Moore’s Aboriginal informants performed the special ritual at Boyay Gogomat in order to propitiate and respect the spirit guardian of the place, as this was a known winnaitch place.

It would be wrong to suggest that because the Red Hill region was regarded as winnaitch that it was totally avoided or uninhabited by Nyungar people. The idea of terra nullius does not apply. There is in fact archaeological evidence to suggest Aboriginal habitation and activity in the Darling Range, including such evidence in the general vicinity of the “owl stone” at Red Hill, where together with the presence of permanent and ephemeral sources of water (see O’Connor et al 1985: 108) and an obvious abundance of indigenous foods, and source materials for stone artefacts and ochre quarries, this could potentially be viewed as constituting a site complex at Red Hill/ Susannah Brook.

2.2 Site Location

The prominent standing stone (referred to throughout this paper as the “owl stone”) was visited and recorded by anthropologists Ken Macintyre and Dr Barbara Dobson in the company of Native Title Holders for the Perth Metropolitan and Darling Range region on 16th October 2008. The standing stone is located at Hanson’s Red Hill Quarry Project Area within Lot 11, Toodyay Road, City of Swan.

To access the site, the recorders were met at Hanson’s Site Office, Lot 11 Toodyay Road by the Red Hill Quarry Manager, Cliff Kelly and Quarry Foreman, Hans Georgi. From the site office the recorders proceeded in a convoy of 4 WD vehicles to a high ridge on the north-western edge of the pit. From here the team proceeded by foot downhill into the steep valley (of the Susannah Brook) and walked for some distance (approximately 250 metres?) to the standing stone. Although the stone structure was visible from a second ridge further down the hill, it was not identifiable as an “owl stone” at that point owing to the angle of viewing, direction and distance remaining to the stone.

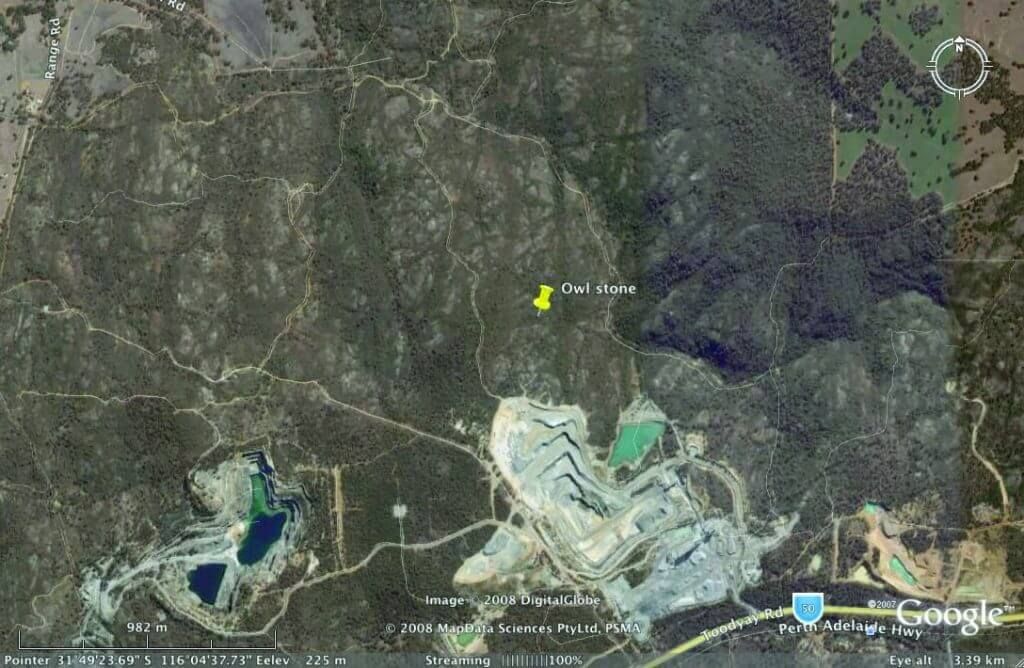

The standing stone is located at MGA coordinates 412740mE 6478860mN (GDA datum 94) and is approximately 180 metres above sea level (see Figure 1 and Plates 1 & 4). According to Hanson’s Red Hill Quarry Manager, the standing stone is situated approximately 170 metres north east of Control 5 (which is at 412501E 6478601N) and is located at RL 191.10 on Lot 11.

The anthropologists are still awaiting the arrival of a map from Hanson’s Construction Materials Pty Ltd which will show the exact location of the site in relation to the current and proposed quarry pit extensions. This map will be forwarded to the Department of Indigenous Affairs and the Native Title Holders as soon as it is received. For the interim period, the location of the “owl stone” in relation to Hanson’s quarry is shown on a satellite map downloaded from Google Earth (see Figure 1).

According to advice from one of the Elders, who was speaking to Hanson’s quarry manager in late January 2009, the pit is currently only 280 metres from the “owl stone”. This is of great concern to the Elders who have requested that a 250 metre boundary be established around the site. Originally a 200 metre boundary was proposed at the time of site registration; however, since then the Nyungar Elders and Traditional Owners have recommended a 250 metre boundary to protect the cultural integrity of the site, as there may be associated sites in the vicinity which have not yet been recorded. Until the Nyungar Elders and Traditional Owners have participated in a thorough Aboriginal heritage survey of Lot 11, and have been reassured that all potential sites of significance to them have been recorded, (and depending on the outcome of these surveys), the 250 metre radius boundary should be respected.

Although the Nyungar Elders who recorded the “owl stone” have bestowed upon it the name Boyay Gogomat, this name must not be confused with the Boyay Gogomat standing stone site visited and recorded by Moore in 1835 in the Lower Chittering area (see Appendix 9.2). None of the Nyungar Elders believed that Moore had visited this particular “owl stone” at Red Hill.

2.3 Site Description

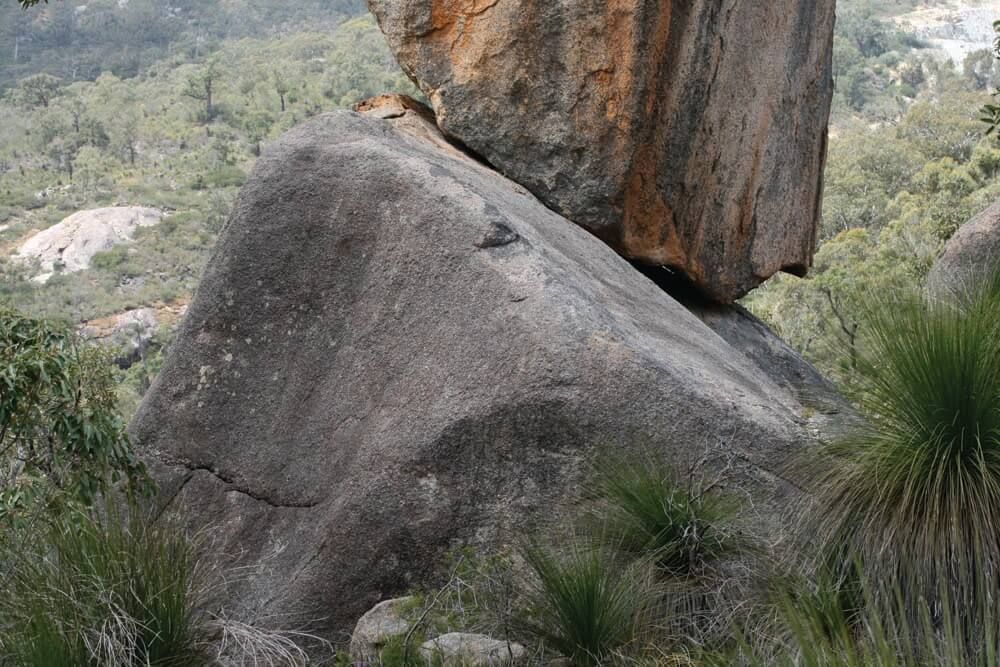

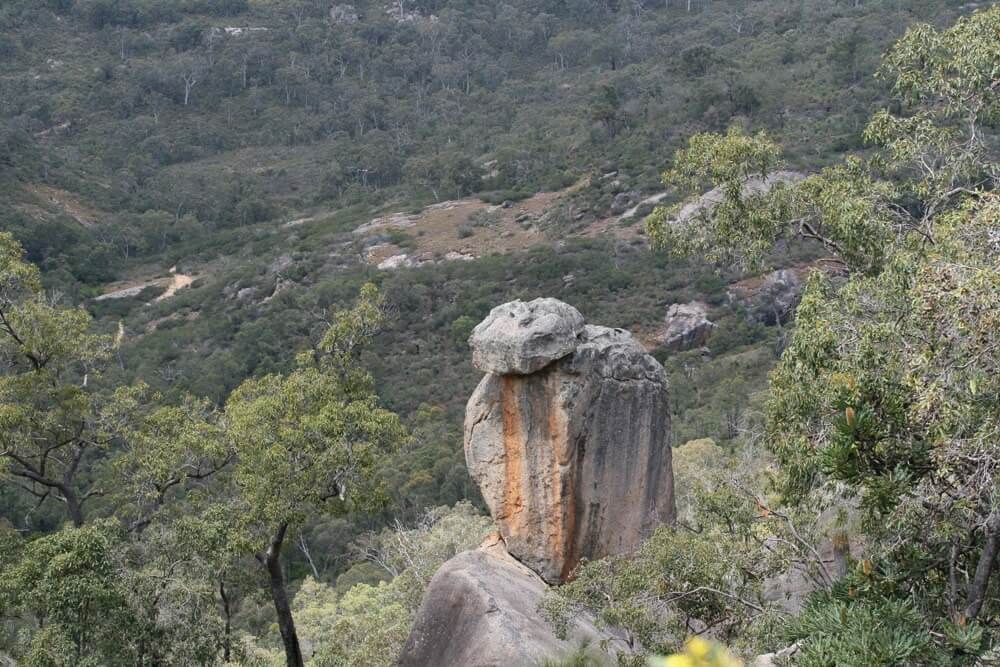

The site consists of a prominent standing stone which is a natural feature composed of weathered granite, made up of three large, remarkably balanced stones (see Plates 1-4).

When viewed from a particular angle the standing stone is in the unmistakeable shape of an owl (probably a Southern Boobook Owl, Ninox novaeseelandia) resting on a stone perch (see Plates 1-4). The owl appears to be facing north-north-west, although the basal stone is oriented in a north-east/south-west aspect (which according to the Quarry Foreman is the same alignment as the surrounding geological seams).

The “owl stone” is approximately 10 metres high and is resting at an angle (see Plate 2) atop a large basal stone which is also approximately 10 metres high (depending on the angle from which the standing stone is viewed). In totality the standing stone is approximately 20 metres high (when viewed from the downhill eastern or south-eastern side) and has a commanding presence overlooking the Susannah Brook (see Plate 4) which is a registered site of Aboriginal significance (Site ID 640).

Underneath the standing stone is a small cavern with a blackened roof (possibly due to smoke) in which several pieces of charcoal and a shell were visible on the floor. One of the Elders observed shell fragments on the floor of a small rock shelter on the eastern side of the standing stone. He believed that these charcoal and shell materials may be of cultural significance. The shell and charcoal materials could not be assessed by the anthropologists as this is outside their scope of expertise, and should have been assessed by an archaeologist.

Native vegetation observed in the immediate vicinity of the “owl stone” includes two prominent (and possibly quite old) Kingia australis (grass trees) which stand almost sentinel to the “owl stone” with Xanthorrhoea preissii (balga), Macrozamia fraseri (djiridgee), Corymbia calophylla (marri), Banksia grandis (boolgalla) which is a favoured source of mungite, nectar, Haemodorum sp. (with bohn-like edible roots) and Thelymitra sp. (sun orchids, with tubers known as djubak) nearby. All of these plants are regarded as providing food and/or medicine (or other resource materials) to Nyungar people.

The “owl stone” is situated on the eastern side of the hill. It is located within the fork of an ephemeral tributary which drains into the Susannah Brook. This tributary (like all other tributaries of the Susannah Brook) is considered by the Nyungar Elders to be part of the previously recorded Susannah Brook (Waugal) site ID 640.

The “owl stone” is situated on the eastern side of the hill. It is located within the fork of an ephemeral tributary which drains into the Susannah Brook. This tributary (like all other tributaries of the Susannah Brook) is considered by the Nyungar Elders to be part of the previously recorded Susannah Brook (Waugal) site ID 640.

2.4 Spiritual Significance

2.41 Contemporary Nyungar views

Some of the views expressed by the Elders with regards to the “owl stone” are recorded here verbatim:

‘When I first saw the stones, it felt like I had found something which had been lost. It was like I had found a piece of a jigsaw that had been missing. You know the feeling you get when you find something that once belonged to you’.

‘This is a very important site to our ancestors here. You can feel ‘the old people’ walking around here.’

‘If I close my eyes, I can see ‘the old people’ sitting down smiling at us, happy that we’re here.

‘You gotta record this place for the Nyungar people. It’s a big place for heritage and culture.’

‘Our sacred sites have been there forever. What gives a white man the right to destroy something so old and sacred.’

‘It’s such a spiritual place to us. We don’t know how to explain it whitefella way, you just feel it all over your body and you know that ‘the old people’ are here.’

‘We knew before we saw it that there was something waiting for us. We could feel it.’

‘The Standing Stone has been there since the beginning of time.’

‘I am part of the Spiritual Dreaming when it begun.’

‘You put up fences to keep us out but you did not take away our Dreaming. It is still there in the land waiting for us to come.’

‘This place is important to us. You can feel it all around. We knew it was here because we saw the engravings over there at Boral’s. They were pointing over here. We knew it was pointing to something really important.’

While standing beside the “owl stone” one of the Elders pointed in an easterly direction across the Susannah Brook valley towards Boral’s [Midland Brick?] whose quarry could be seen in the distance. The Elder explained how when he had visited the rock engravings “over there” [at Boral Resources] that they were pointing at something significant “in this direction” [Red Hill]. He was now convinced that they were pointing to this particular standing stone site. He notes:

‘There will be other “pointers” all up the valley to mark the way for the ‘old fellas’ coming down from the east. All along the old trails there would be markers for this one and other places of importance along the way.’

‘The old owl is a living stone to us. We can feel its spirit giving life.’

‘Can’t you feel the sacredness of that stone. You don’t need to touch it; just being near it is enough.’

‘That stone is so spiritual that it talks to me in my sleep.’

For further views, see Robert Bropho’s statements of significance (Appendix 9.4).

2.42 Ceremonial Rituals of Respect

‘In Nyungar culture the googoo or boobook owl is a frightening messenger of death. The owl stones are very dangerous if not approached with caution and respect.’

While visiting the “owl stone”, the anthropologists Macintyre and Dobson observed the reverential respect given to the site by the Elders, who carried out the ritual of carefully placing Xanthorrhoea fronds around the base of the stone, in accordance with how they carry out the customary ritual and respect paid to an important spiritual place such as this. (See Appendices 9.2 & 9.3 for reference to this ritual as described by George Fletcher Moore 1835 in relation to the owl stone at Lower Chittering).

The Elders emphasized that when visiting the ‘owl stone’ everyone must respect it and ensure that the proper ritual is performed in a culturally appropriate manner. They commented that if people respected the site, it would not be dangerous to anybody who visited it, whether male or female.

2.43 Spiritual Reconnections

The ritual of placing the Xanthorrhea leaves not only shows a deep sense of respect to the Ancestors but also enables a re-energising or reconnecting in a spiritually respectful way with their ancestral past. As one of the Elders stated: ‘being close to the stone gave me a feeling of exhilaration and purpose.’

Some of the Elders expressed views after visiting the “owl stone” that they had experienced a sense of spiritual and psychological uplifting. They said they had felt “spiritually stronger” and “joined up” to their ancestral past. Another Elder reported that when he visited the stone, he felt as though time had momentarily stopped still.

The male Elders confided that they had experienced dreams either prior to, or after, visiting the “owl stone.” One Elder who did not attend but who had visited the “owl stone” on a previous occasion, told how he had experienced a vivid and revelatory dream associated with the owl. Another Elder told how he had experienced an impacting dream involving the visitation of an owl to his house. He said that when he had the dream interpreted by an elderly Aboriginal woman from the Busselton region she told him that a powerful totem spirit was visiting him to connect him to the Spiritual Dreaming. For privacy reasons the contents of the Elders’ dreams cannot be published in this report.

All of these unexplainable psychological phenomena could be interpreted under the rubric of religious experience, or as one Elder put it “connecting with the ancestors.”

When visiting old places which they believe to be of significance, Elders often speak of “seeing” ‘the old people’ walking through the area collecting food, camping and performing rituals. When the Elders speak, it is never in the past tense but is as if they are witnessing it in the here and now. In some cases, and this was illustrated by their visit to the “owl stone,” they describe ‘the old people’ (ancestors) as “happy” to see them and “very welcoming”.

On a number of occasions Nyungar Elders have tried to explain to us that even though they have long been dispossessed from their land (and sacred sites), the spirits of the Dreaming are ‘still there’ in the land’ “waiting” to spiritually reconnect with them. As one Elder expressed it:

‘These old sites are not lost. They’re being looked after by ‘the old people’ [ancestors] who have been waiting for us to come and take over from them.’

Although such a view may be difficult to comprehend from a non-indigenous viewpoint, from a Nyungar viewpoint it is a culturally relevant, valid and legitimate means of recognising a place of cultural significance.

It is difficult for white anthropologists to describe, far less quantify, the powerful ethnopsychology involved in indigenous people’s own (as yet) unexplained ability to locate places of spiritual and cultural significance to their people. It is surely time to rethink the conventional criteria employed in indigenous site assessment and to adopt a broader, less Eurocentric-based approach which indeed recognises indigenous means of site identification.

McDonald, Hale and Associates (1998: 22) also acknowledge the distinctive ways that Nyungars use to identify sites. They refer to this as “feeling the country”:

‘Many Nyungars also report that they are able to feel the presence of spirits and/or ‘sacred’ (eg mythological) sites …. It is not uncommon, however, for individual Nyungars to report the presence of sites on the basis of feelings or other types of apparent extrasensory perceptions (i.e. hearing voices, feeling an unusual wind, experiencing body tremors and so on)…. The ability to feel or perceive the presence of spiritual matters is often highlighted by Nyungars as an important difference between themselves and non-Aborigines.’

The above quote merely reinforces our argument that Aboriginal people have the innate ability to intuitively experience or “tune in” to places that are of cultural significance to them. As one Elder commented in relation to the “owl stone” ‘these places are the important Spiritual Dreaming places of our ancestors and we are part of that.’ The Elders had no doubt that their Nyungar ancestors had performed ceremonies and known the deep mythology for the place. This mythology would have explained how the totemic (ancestral owl) being came to be associated with the area. Such information would have been secret-sacred and not revealed to outsiders or the uninitiated.

Salvado (1850 in Stormon 1977: 125) emphasizes that Aboriginal people were highly protective of their religion and that ‘either through cunning or traditional secrecy’they carefully hid their ‘special habits and beliefs from strangers’.

The Nyungar Elders and Traditional Owners perceive the “owl stone”” (“Boyay Gogomat”) at Red Hill as an important symbol of their “Spiritual Dreaming” of which they are a part. They believe that the quintessential spirit of the Ancestral Owl is “still there in the landscape” and that it becomes incorporated and inter-linked with a much larger and dynamic totemic landscape. It is for this reason that the Elders do not perceive this stone as an isolated feature but rather as part of a story or mythological Dreaming Track which links to a network of Ancestral Beings who are “waiting” (in contemporary Nyungar terms) to be reconnected to their contemporary Nyungar families.

This idea of the spirits of the Dreaming “waiting” to be discovered or to reveal themselves to humans may not be such a strange idea. As noted by Mircea Eliade, a historian of religion:

‘In actual fact, the place is never ‘chosen’ by man…It is merely discovered by him…The sacred place in some way or another reveals itself to him…The notion that holy ground chooses rather than is chosen constitutes the core of innumerable spiritual traditions across the planet.’ (Eliade cited in McLuhan 1996:6).

3.0 ANTHROPOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE TOTEMIC AND MYTHOLOGICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF THE “OWL STONE”

For information on the significance of owls and other night birds in traditional and contemporary Nyungar culture, see Appendix 9.8. This research paper provides an overall context and insight into the nature and complexity of Nyungar views on owls and may help the reader to better understand the occurrence and significance of “owl stones” in Nyungar culture.

To understand the cultural significance of the “owl stone” within the context of the Red Hill area requires an understanding of the concepts of winnaitch, totemism and what contemporary Nyungars refer to as their “Spiritual Dreaming”. (For information on the Nyungar notion of winnaitch, see Appendix 9.3). The notions of ‘Spiritual Dreaming’ and totemism are explained below.

3.1 The Spiritual Dreaming

‘Our Spiritual Dreaming is in the land.’

‘You put up fences to keep us out but you did not take away our Dreaming. It is still there in the land waiting for us to come.’

In an attempt to understand the Nyungar concept of “Spiritual Dreaming” it is useful to consider Elkin’s (1943:171) notion of ‘the eternal dream-time’ and Berndt’s (1968, 1973) definition of ‘The Dreaming’. Elkin (1943: 187) points out that the ‘eternal dream-time’ incorporates ‘past, present and future, [which] are, in a sense, co-existent – they are aspects of the one reality.’ “The Dreaming” according to Berndt (1973: 31) is:

‘… a synthesizing concept, uniting human beings and natural species, the land, the sky and the waters, and all within or associated with them: and that relationship is cemented or made irrevocable by spiritual linkages with or through mythic or spirit beings.’ (Berndt 1973: 31)

It is well documented in the anthropological literature that the traditional animistic and totemistic religion of the Australian Aborigines was nature-based and commonly focused on “natural” features of the environment, including rock features, especially those which stood out or resembled aspects of the surrounding bird, plant or animal life. Such places were often considered sacred as they formed an important part of the traditional totemic mythology of the landscape. Elkin (1943: 136-137) refers to the “inextricable” connection between mythology and totemism:

‘It is fundamentally the mythology which records the travels and actions of the tribal heroes in its subdivision of the tribal territory. The country of each local group is crossed by the paths or tracks of these heroes along which there are a number of special sites where the hero performed some action which is recorded in myth; it may have been only an ordinary everyday act, or it may have been the institution or performance of a rite. A site with its heap of stones, standing stone [emphasis added here], waterhole or some other natural feature, may mark the spot where he rested or went out of sight temporarily. Another may mark the final stopping place where his body was transformed into stone and his spirit was freed to watch everything which should happen afterwards [emphasis added] or, possibly it may be the “home” where his spirit awaits incarnation. In some cases too, such a hero is believed to have left the pre-existent children in the spirit-centres, in the same way as by his rite and actions and the virtue inherent in him, he caused certain places to be the life-centres or spirit-centres of natural species’ (Elkin 1943: 136-137).

Although Elkin’s work primarily relates to South Australia, Central Australia, Northern Australia and north Western Australia, his structural analysis of totemic sites and mythological “paths” may also be applied to the ancestral landscape of south-western Australia. However, owing to the absence of any ethno-historical or ethnographic information having been recorded for the “owl stone” at Red Hill, one can only speculate as to which of Elkin’s explanations may apply here.

The “owl stone” may potentially represent the “final stopping place” where the body of the Ancestral Owl Being became metamorphosed into stone and his spirit released “to watch everything which should happen afterwards.” This idea is reflected by Elders’ comments:

‘That old owl is sitting there watching everything. That bird can see a long way and knows everything that happens.’

‘That owl has been there for thousands of years and now it’s just sitting there everyday watching the quarry getting closer and closer.’

These ideas are difficult for non-indigenous people to grasp and can only be comprehended by understanding the indigenous context from which they come.

Elkin (1943: 177-178) attempts to understand the significance of totemic stone in Aboriginal culture when he writes:

‘But whatever be our philosophical, sacramental and symbolic interpretation, we realize that the sacred stone or heap is not, for them, just stone or earth. It is in a sense animated: life can go forth from it.’

This same idea is illustrated by one of the Nyungar Elder’s statements about the “owl stone”:

‘That old owl is a living stone to us. We can feel its spirit giving life.’

Thus the “owl stone” is not only viewed as tangible evidence of the mythic past but is also viewed and valued by contemporary Nyungar people as a “living” ancestral guardian spirit being which signifies the past, present and future merged into one reality, that of the “Spiritual Dreaming”. This spiritual consciousness expressed by the Nyungar Elders is indeed a “reality” to them. In an attempt to understand this “reality” of indigenous spiritual experience in relation to totemic stones, it may be useful to consider Mircea Eliade’s (1957) notion of ‘supernatural reality’ and, in particular, his statement about the perceived powers of sacred stones and how these powers manifest themselves in “pre-modern” societies (see Appendix 9.5).

The following quote from Berndt (1992:137) provides some insight into the powers associated with natural features and the “continuing” spiritual significance and influence of totemic mythological ancestral beings:

‘The great mythic beings of the Dreamtime established the foundations of human socio-cultural existence. They also attended to that environment, and in many cases were responsible for forming it. They created human and other natural species and set them down, as it were, in specific stretches of country. They are associated with territories and with mythic tracks, and in many cases were themselves transformed into sites where their spirits remain; or they left sites which commemorated their wanderings – in which case, part of their spiritual substance remains there. So, all the land was (and is) full of signs. And what they did and what they left is regarded as having a crucial significance for the present day. But more than this, they are considered to be just as much alive, spiritually, as they were in the past. They are eternal, and their material expressions within the land were believed to be eternal and inviolable too.’

3.2 Totemism

‘It’s like an older brother, this stone. It will not harm you but will protect you from danger as long as you respect him. I feel really calm here.’

‘A totem is an object toward which members of a kinship unit have a special mystical relationship, and with which the unit’s name is associated. The object may be animal, plant or mineral…In totemism, the totem animal cannot be killed or eaten except under very special circumstances. The totem will be treated both in life and death like a fellow tribesman…The totem’s essence or religious power is often linked to the clan’s emblem and is often a sacred object.’ (Winick 1966: 542).

The anthropological notion of the totem as a “sacred object” is important. In the case of the “owl stone” the object of reverence is a standing stone which is believed by Nungar Elders to be endowed with the living essence of the totemic ancestral owl (Gogomat) who once moved through the country creating significant aspects of the geology and geography. It is not uncommon for natural features of the landscape (such as standing stones, ridges, hills, rivers, lakes and rock holes) to be viewed as part of the Spiritual Dreaming and to have totemic cultural significance. As noted by Berndt (1965: 230):

‘Totems are often associated with places marked by striking or unusual physical features. A hill, a rocky outcrop, a deep pool, or something of the kind, is accepted too as a sign left by the mythical participants in a marvel supposed to have occurred there. Such places are to be approached and treated with a formality ranging from respect to reverence. In certain cases they may be made the scenes of “rites of increase.’ These are rites to maintain and renew, or conserve and produce the totem.’

A totem is a bird, plant, animal or other object recognised as being ancestrally related to an individual or group. It links humans, non-humans and the land. When Berndt (1973: 33) refers to ‘spiritual linkages with or through mythic or spirit beings’ which serve to connect humans to their natural environment and the Dreaming, he is referring to what anthropologists commonly call totemism, a kind of spiritual kinship which unites humans with their physical and social environment. Berndt (1973:33) comments that within this environment: ‘certain aspects were selected to serve as material representations of the spiritual (and mythic) activators, who were believed to have breathed life into it.’

Although Berndt (1973: 32) illustrates this concept using the kangaroo as an example, the same could be said about the owl (Gogomat):

‘in the creative era, a particular mythic being was shape-changing, either animal or human in appearance, with the power to ‘turn’ or change shape, becoming say a kangaroo as a result of a particular event or incident that occurred in the myth: or creating a kangaroo. Because of this, all kangaroos today have a spiritual connection with their progenitor or creator, and the mythic being himself (or herself) is manifested through all of them. Also, that particular mythic being is responsible for human beings – some human beings: all those born or conceived at, or otherwise associated with, the actual place where the mythic event took place (where the mythic being ‘turned’ himself or performed the act of creation) are spiritually linked with him: they are one of his manifestations -just as kangaroos are. A spiritual affinity binds them together, underlining their interdependence; all have something in common.’ (Berndt 1973: 32)

The equivalent notion for totem in the Nyungar language is kobong (Grey 1840) or its variants coubourne or cubine (Hassell 1934, 1936, 1975). These terms refer to the same concept which Grey (1840: 64) describes as follows:

‘ko-bong – a friend, a protector.-This name is generally applied to some animal or vegetable which has for a series of years been the friend or sign of the family, and this sign is handed down from father to son, a certain mysterious connection existing between a family and its ko-bong, so that a member of the family will never kill an animal of the species to which his ko-bong belongs, should he find it asleep; indeed he always does it reluctantly, and never without affording it a chance of escape. This arises from the family belief that some one individual of the species is their nearest friend, to kill whom would be a great crime, and is to be carefully avoided.’

This is similar to Elkin’s (1943: 129) view of a totem as an “assistant”, “guardian” or “mate” or symbol of the social group to which the individual belongs. Elkin (1943) emphasizes the importance of the ‘bonds of mutual life giving’ between humans and their kin totems. Other key aspects of the totemic relationship include obligations of mutual caring, respect and protection.

3.3 The Mopoke as a Totem

Ethel Hassell was the first to record the totemic significance of the mopoke (or what she called “mopoak”) in Nyungar culture. While collecting ethnographic information from the Wheelman people in the southern part of Western Australia as early as the 1870’s at Jerramongup she notes the totemic significance of the mopoak (sic) as follows:

‘cubine – the mopoak [sic.] (a night hawk), a species of owl which flies silently and has a note like the howling of the dingo. A totem.’ (Hassell in Davidson 1934:277)

The fact that Hassell records cubine for mopoak (sic) suggests that she was in fact recording (probably without realising it) the Nyungar word for ‘totem’ (cubine) rather than the Nyungar name for ‘mopoke’. She also records coubourne (a variant of cubine) as meaning totem (1936: 684) and notes that ‘Every native had one or more totems which he was not allowed to eat or destroy.’ She highlights the fact that totems were assigned importance depending on their position within a hierarchy with those “of the highest degree” being the flying birds (1936: 684). She records the mopoke as being at the top of this hierarchy.

Hassell (1975: 212) not only records the mopoke as a totem bird but also records an “owl stone” in both the mythology – and in the actual landscape at Cape Riche/ Bremer Bay. This owl stone is noted by Hassell as one of a number of totemic rock features which she observed along the south coast of Western Australia:

‘There are many curious rocks all along the south east coast which assume most peculiar shapes. Some have legends and doubtless they all had, but many have been forgotten. In Albany the Dog’s Head Rock is well known….Near Cape Riche there is one strongly resembling an owl which has a legend…(See Appendix 9.6 for details of this “owl stone” mythology).

Hassell (1975: 180) describes this owl stone, which she personally observed, as ‘…a large stone, the shape which looks like a mopoke and has two dints making the eyes.’ When camping with her husband and children in a rocky cove at Bremer Bay in the vicinity of the owl stone, she further remarks:

‘There were several natives there, two of which belonged to Cape Riche, and they seemed quite delighted to think I had noticed the mopoke or cubine rock. There was a good deal of talk about the story of the rock and the reef which seemed to be fairly well known by our natives [the Wheelman at Jerramongup]. Indeed they supplied the first part of the story while Cape Riche natives finished it.’ (Hassell 1975: 181)

Further to Hassell’s work on totemic owls and owl stones, Mathews (1904: 51) writing at the turn of the century, similarly notes that the mopoke was an important totem which was associated with families in traditional Nyungar society. He points out that the mopoke totemic group was a subdivision of the Wortungmat (crow) phratry.6 Like in many other Aboriginal groups throughout Australia, Nyungar society was traditionally divided into two halves, or what Bates and Mathews refer to as primary phratries (moieties), which are described as follows:

‘These divisions are called Wordungmat and Manitchmat (or Manaitchmat) respectively and mean Crow stock (wordung-crow, mat or maat – leg, family, stock), and White Cockatoo stock (manitch or manaitch – white cockatoo).’ (Bates in White 1985: 192)

The association of the mopoke group with the Wordungmat (crow) phratry is indeed culturally logical in view of Bates’ assertion (in Bridge 1992) that the Wordungmat (crow) subdivision represents the “dark” side (and Munitchmat, white cockatoo, the “light” side) of the Nyungar moiety system. The mopoke with its nocturnal habits and its perceived associations with the supernatural logically symbolises the ‘dark’ side.7

3.4 Ancestral Owl Dreaming Track – Boyay Gogomat

It should be highlighted that the “owl stone” (known as Boyay Gogomat) at Red Hill is not the same Boyay Gogomat (standing stone) visited and recorded by Moore in 1835 in the Lower Chittering area. None of the Elders believed that Moore had visited the “owl stone” at Red Hill overlooking the Susannah Brook valley. As one Elder stated:

‘We don’t think Moore came to this place. He might have gone to another place with the same name. There are other owl stones in different places because that owl ancestor moved around, like the Waugal did and the other ancestors. Those “old people” would have called it by the same name wherever it went, as a mark of respect, but everywhere it went it had a different story. We don’t know these stories because ‘the old people’ kept them secret, and they wouldn’t have told Moore because this is winnaitch [forbidden, taboo, sacred, secret].’

This view of Boyay Gogomat as a cultural manifestation of Moore’s Boyay Gogomat – but in a different location – is highly significant. The Elders describe the ancestral owl (Gogomat) as travelling around the country at the beginning of time helping to create the topography and then, as with many of the other Ancestral Beings, becoming metamorphosed into the land at different places along the Ancestral Track to become “sites” which remain to this day as prominent features of the landscape. Linguistic and anthropological evidence tends to support this idea of the ancestral, totemic and mythological importance of Boyay Gogomat (as the following analysis shows).

Our linguistic research shows that Boyay Gogomat literally translates as ‘Stone Ancestral Owl’ (Boyay, stone + Gogomat, Ancestral Owl). This meaning derives from the work of Bates (1985) and Douglas (1976) who note that ‘mat,’ or ‘maat’ literally means ‘leg,’ but can also mean “family”, “lineage” or “stock”, hence Gogomat may also denote owl family/ group/ stock. Bates popularises the term ‘mat’ in her classic reference to the Wordungmat and Mannitchmat moieties – the two halves of Nyungar society which interestingly possess bird names. The ‘mat’ in Gogomat may be viewed as a totemic reference denoting “family,” “stock ”or “group” (Douglas 1976).

As previously noted the ‘owl group’ (gogo, owl + mat, group) may be viewed as one of a number of sub-groups of the Wordungmat moiety, or what Mathews (1904) refers to as the mopoke family group. In this context the affix ‘mat’ may be viewed as an indigenous body part metaphor which denotes a kin grouping or ancestral descent line from a common totemic ancestor (the Ancestral Owl).

Douglas (1976), a specialist in Nyungar linguistics, provides further support for the indigenous view of Gogomat as signifying or belonging to the Ancestral Owl Dreaming. He notes that ‘mat’ not only means leg but is also a metonym for ‘way’ or ‘path’ and “refers also to a particular sacred or totemic ‘path’ or ‘group”. Douglas (1976) gives the example of ‘wetjamat’ (wetj, emu + mat, group) which he translates as ‘belonging to the emu group/path/mob’. By substituting Gogomat for wetjamat, the meaning becomes ‘belonging to the owl group/path/mob and refers to “a particular sacred or totemic ‘path’ or ‘group.”

Nind (1831 in Green 1979: 52) also records the body part “maat” as meaning “path”. Thus both Nind and Douglas provide linguistic support for the Nyungar view of the “owl stone” as marking an important “place” or site on the mythological track (‘mat’) of the Totemic Ancestral Owl Being (Gogomat).

Elkin (1943) and Berndt (1973) in their anthropological analyses of the structure of Aboriginal myth refer to the importance of “turning” points and the “final stopping place” of the Ancestral Beings. These are relevant to an understanding of the totemic significance of “owl stones” in Nyungar mythology. For example, Berndt (1973: 79) refers to “the actual place where the mythic event took place (where the mythic being ‘turned’ himself…)’ as follows:

‘The most dramatic incident in a story may be the last of all, when the characters are transformed into something else, and die physically in order to achieve some other state of life.’ (Berndt and Phillips 1973: 79)

This is the same as Elkin’s (1943: 136) notion of ‘the final stopping place’ of the Ancestral Being. However, whether Boyay Gogomat at Red Hill represents the “turning” or “final stopping place” of Gogomat, the Ancestral Totemic Owl, is not known as there are no specific recorded mythological details.

However, there is an “owl stone” which features in the Nyungar mythology of the South Coast region of Western Australia, which was in fact visited by Hassell in the 1880’s. The traditional version of this myth was recorded by Hassell (1935, 1975) and a more contemporary version was collected by Macintyre (1975) (see Appendix 9.6). These myths and beliefs appear to conform to Elkin and Berndt’s structural model in that the “owl stone” represents the end part (or crux) of the story whereby the owl dies and becomes immortalised in stone on the side of the hill overlooking the ocean, continuing to watch everything that’s going on. The owl/ norn (tiger snake) story which relates to the Nyungar mythology of the Jerramongup to Bremer Bay region may provide some insight into the owl/ Waugal theme found in other parts of the south-west region.

Like other metamorphosed remains of Ancestral Beings located throughout the country, “sites” such as Boyay Gogomat (at Red Hill and Lower Chittering) remain to this day as prominent features of the totemic geography and living history of the Ancestor’s presence in the land.

As noted by Berndt (1964: 187-188) referring to the concept of the Aboriginal Dreamtime:

‘Briefly, this concept means that the beings said to have been present at the beginning of things still continue to exist. In a spiritual, or non-material fashion, they and all that is associated with them are as much alive today, and will be in the indefinite future, as they were.’

Berndt (1964: 188) further expands on this as follows:

‘The mythological era, then, is regarded as setting a precedent for all human behaviour from that time on. It was the past, the sacred past; but it was not the past in the sense of something that is over and done with. The creative beings who lived on the earth at that time did perform certain actions then, and will not repeat them: but their influence is still present [emphasis added] and can be drawn on by people who repeat those actions in the appropriate way, or perform others about which they left instructions. This attitude is summarised in the expression ‘the Eternal Dreamtime’, which underlines the belief that the mythological past is vital and relevant in the present, and in the future. In one sense, the past is still here, in the present, and is part of the future as well [emphasis added]. In another but relevant context, the spirits of deceased human beings are still alive and indestructible. The mythical characters themselves are not dead…Their physical human shape was simply one of a number of manifestations…’

‘In the formative period, the various species had not finally adopted the shapes in which we see them today. Their physical manifestations were a little more fluid than they are today. Many mythical beings, all through Aboriginal Australia, were either more or less than human according to the way in which we look at it. The life force which they embodied was not limited to a human manifestation, but could find expression also in the shape of some other species. A goanna ancestor may have looked like an ordinary human being, but at the same time he was potentially capable of changing his shape and taking the form of a goanna. This identification in the mythological past has continuing consequences today. Because of it, there is said to be a special relationship between certain human beings and, for instance, that particular kind of goanna.’

If ‘owl” is substituted for ‘goanna’ here, the same logic applied to Nyungar totemic mythology. As one of the Elders pointed out, when the head of the owl (“owl stone”) at Red Hill is viewed from a particular angle, it resembles the outline of a human face (see Plate 3). He said that this was significant as

“those old ancestors could change from being birds and animals to humans like the old bulya men.”

Berndt (1989: 406) comments on the shape-changing powers of Ancestral Beings:

‘One of the characteristics is that the mythic personages have magical and supernatural powers. They are able to change their shape, transform themselves and perform remarkable feats that are beyond the ability of ordinary human beings.’

Furthermore, it is well-recognised in the anthropological literature, and indeed in stories relating to ‘the Spiritual Dreaming’, that the totemic Ancestral Beings not only have the personalities and behaviour of humans but it is in fact often difficult to ascertain (at any particular time during the story telling) whether they are referring to humans or animals. This human/animal duality becomes so blurred that it is difficult to separate the human from the non-human. As one Elder commented:

‘There is no separation or duality between humans and animals. Ancestral Beings says it all.’

An interesting aspect of this duality is found in Aboriginal sites where the totemic ancestors’ dismembered body parts are sometimes represented in the physiography of the land. These body parts, especially in the case of phallic symbols, resemble the human anatomy, even though they are attributed to the ancestral animal or bird. This simultaneous duality of human and non-human form is often (but not always) demonstrated or ‘evidenced’ in the metamorphosed totemic features in which the human aspect may form a major or, in the case of the “owl stone” at Red Hill, a minor aspect (see Plate 3).

In establishing the importance of the totemic ancestral “owl stone” at Red Hill, one may ask is it a coincidence that some of the traditional Nyungar place names in the Susannah Brook, Avon River and Boyay Gogomat locations at Lower Chittering and Red Hill translate as ‘owl’? There may also be present in these areas other “owl stones” or sites associated with the Gogomat Dreaming which have not yet been located.

What should be highlighted here is the fact that the traditional Nyungar name for the Avon River (or part of it) is Gogulger (Lyon 1833 in Green 1979: 179). This is remarkably similar, if not the same traditional name as Goolgoil which refers to the upper part of the Susannah Brook (see Drummond 1836, Appendix 9.1). Both may translate as owl, or in the case of Gogulger, ‘owl people’.8

One could speculate that the term Gogulger refers to a group of people belonging to a particular geographic location or territory, whose ‘district totem’ was the owl or mopoke. According to Bates (in White 1985: 193): ‘The district totem belongs to all the members born in such district’. She gives as examples of ‘district totems’ the black swan (Gingin) and the banksia (Swan District). A district totem may be viewed as a strong organisational emblem which signifies and unites a district descent group or local territorial group.

It is possible that Gogomat fits into Elkin’s (1943) concept of ‘clan totem’ or ‘local totem’ (the difference being that ‘clan totemism’ is descent- based whereas ‘local totemism’ depends principally on locality rather than descent). ‘Local totemism’ is associated with the local group (or local subdivision of the tribe) which Elkin (1943: 39) defines as:

‘normally both territorial and genealogical. That is, a definite part of the tribal territory belongs to, or is associated with, a group of tribes folk who are mutually related in some genealogical way.’

Elkin (1943) points out that the totemic aspect of the local group is primarily involved with ‘the sacred and ceremonial life’:

‘members belong to the local group because their spirits belong to its country, and to definite “homes” along the path of some great culture-hero and ancestor in that country. In many tribes, each local group is also a distinct totemic clan.’ (Elkin 1943: 73)

The question of whether Gogomat once represented what Bates refers to as a ‘district totem’ or ‘local group totem’, or what Elkin refers to as a ‘clan totem’ or ‘local totem’ is purely speculative. It is our view that Gogomat was possibly a territorial totem which linked individuals and their groups to a “home” country with which they had strong religio-mythic affiliations.

What is significant, however, is the contemporary Nyungar view that Boyay Gogomat marks an important site, or sites, along the Ancestral Owl Spiritual Dreaming Track. This makes sense when viewed within the broader geographic context of the Avon River and the upper Susannah Brook and surrounding hill country, together with the sacred “owl stones” (or Boyay Gogomat) sites at Red Hill and Lower Chittering, all of which have indigenous names which when translated indicate owl totemism and symbolism.

3.5 Owl Dreaming, Totemism and Symbolism in other parts of Aboriginal Australia

There are numerous references in the archaeological and ethnographic literature to owl dreaming, symbolism and totemism in other parts of Aboriginal Australia, including the Kimberly region of Western Australia, the Northern Territory, Queensland and New South Wales.9 Like the ancestral owl Gogomat who was perceived as an almost deity-like being with the power to transform birds into humans (and vice versa) and to create harmony out of chaos in human society, ancestral owl beings in other parts of Aboriginal Australia also reigned supreme in the creation myths, and in the imparting of Law and knowledge to humankind. 10

Interestingly, McCarthy (1940: 184) distinguishes several different categories of “stone arrangements” in Aboriginal Australia. Under the heading of “monoliths” he refers to a natural stone feature located in Worora country in the West Kimberley representing the ancestral boobook owl. He describes this as follows:

‘Another set of four elongate stones set up on a hill overlooking an arm of the sea are said by the same tribe [Worora] to indicate the spot where a boobook owl stopped the sea from flooding the land. As the tide rose the owl seated itself on this hill and when it heard the owl’s fearful cry and saw its big eyes, the sea drew back.’ (p. 185)

See Mowaljarlai’s (1993) reference to the boobook owl in the foundation myth of Worora and Ngarinyin society. 10

McCarthy (1940: 185) further notes that: ‘Numerous instances may be quoted of monoliths, natural and artificial, forming totem-centres in north-west Australia.’ He comments: