The Shark in Nyungar Culture

Prepared by Ken Macintyre and Barb Dobson

Research anthropologists

‘There were no canoes amongst the Southern coastal people. They swam in the estuaries and rivers, but the mamman waddarn (father sea) was always too angry for them to venture into it, and they never troubled about the islands beyond swimming distance. There is a tradition both in the Swan and Murray districts that a native once swam out to Rottnest Island and returned saying that ‘the place was full of sharks.’ No other native followed his example. Garden Island and other reefs and islands on the south-west coast were supposed to have been at one time connected with the mainland, but since they became islands no native has ever swum to them.’

(Bates in White 1985: 253)

To coastal and island Australian Aboriginal people the shark has long symbolized bravery, fearlessness and uncanny powers. Large sharks were perceived in mythology as the spirits of creation and destruction and were revered and feared. Being the legendary top predator of the ocean the shark was often deified and demonized as it was in other island cultures of the world. It is easy to imagine how these ancient creatures were seen to be a spiritual channel to the underworld of the ocean and jealously guarded as the totem familiar of the powerful sorcerer.

Large species of sharks found in the marine, estuarine and riverine environments of southwestern Australia were regarded with great awe, respect and often dread by the traditional inhabitants. We have little documented ethno-historical information on Nyungar traditions involving the many different types of shark found in their coastal environment but based on the limited information available it would seem that the shark played an important role in the spiritual and indirectly the economic life of coastal and riverine Nyungar people. We hope that this paper will provide an ethnographic glimpse into this little known aspect of traditional culture. Some Nyungar names for shark are maadjit (Grey 1840: 76), bugor (Moore 1842) and moon-do (Grey 1840).

Martiat (maadjit, matchet) – shark

Phillip Parker King was the first to record the Nyungar name for shark. In 1821 when camped at Oyster Harbour at King George III Sound (also known as King George Sound or King George’s Sound) he recorded mar-git as ‘a shark or shark’s tail.’ Later on Nind (1831: 33, 49) the resident medical officer at the KGS settlement between 1826-1828 recorded martiat as the local Aboriginal name for shark. He writes:

‘Although sharks are very numerous, the natives are not at all alarmed at them, and say that they are never attacked by them. Sometimes they will spear them, but never eat any part of the body.

Von Hugel (1834 in Clark 1994: 76, 86) describes King George Sound as ‘chock-full of sharks.’ There is no doubt in our minds that the Nyungar people must have taken into consideration the hazards of hunting shark and stingray and as these were not eaten, hunting them would have been a purposeless exercise. The coastal Nyungar had no watercraft and according to some early sources did not know how to swim. We find these references to their inability to swim hard to believe. It is more likely that they were extremely cautious and did not venture into waters that potentially contained harmful creatures, such as sharks. Daisy Bates’ italicized quote at the beginning of this paper suggests that the Nyungar knew how to swim but were too fully aware of the dangers that lurked in the coastal and riverine environments that were a part of their everyday lives causing anxiety about entering deep water.

Phillip Parker King observed their anxiety around deep water:

‘Like Vancouver, King was perplexed that the Aboriginals living around the shores of King George the Third’s Sound had no water transport. On his voyages around Australia he had constantly found canoes, rafts and floats of one kind or another, and people who were as much at home in the sea as on land. But these people seemed terrified of the water and, while being ferried out to board the brig, were in a continual state of alarm.’ (Hordern 1997: 334).

Aborigines knew their environment well and kept to the shallows of rivers and estuaries where they could see the fish they were spearing. When they ventured up rivers and streams they took extra precautions to keep themselves safe as noted by Nind (1831) as follows:

‘Though not afraid of sharks in the shallow water of either of the harbours, yet in the river connecting the lakes with Eclipse Bay, they are extremely timid and will not venture on the trees overhanging the banks.’

In sections of deep rivers where fish were present, fallen trees and overhangs were often used as vantage points for fishing (see Figure 2). Was it the river shark that they were fearful of or some other menacing spirit of these dark waters? We think from Nind’s (1831) description that the culprit was probably the dusky shark or river whaler (Carcharhinus obscurus), a less well-known cousin of the ill-famed bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas). The dusky shark, which is also known as the black whaler, is found in the rivers, estuaries and marine waters of the Albany region. It is described by Prokop (2000: 182) as follows:

‘A very dangerous species which is often found in areas frequented by people. The black whaler is common in inshore waters and may move up coastal rivers to pure freshwater. The black whaler has been responsible for a large number of attacks, some of which have been fatal…. can also follow schools of mullet well into fresh water, herding them into the shallows…’

A.Y. Hassell (1894) demonstrates how places of danger were clearly signposted within a traditional mental map of their territory. He records magetup as ‘shark in pool’ no doubt referring to a dangerous place (pool) where sharks were known to frequent, or become stranded, possibly in shallow or upstream river waters (‘up’, ‘place of’ + maget, shark), as referred to by Nind (1831).

The place name magetup would have alerted indigenous fishers and waders to be extra cautious, although Hassell does not clarify whether he was referring to a freshwater or saltwater pool. His wife Ethel Hassell (1936:278, 1975:232), who was observing Aboriginal traditional culture in the 1870’s and 1880’s in the Jerramongup – Bremer Bay area records marghet (or marget) as a feared ‘water spirit who lives inland.’

Could this inland water spirit be the same entity as maget the shark found in pools? We think so, especially given the context of what potentially lurks in the deep and opaque river pools of southwestern Australia, namely the dusky shark in the Albany region and its cousin the bull shark in the Perth-Canning River area. Both are dangerous river whaler sharks found in both saline and freshwater environments.

In southwestern Australia most estuarine fishing was done on sandy shoals in clear shallow waters and it is well known that the Nyungar avoided water deeper than knee height (matta-garup). The places where they forded rivers were called matta-garup. The popular traditional crossing at Heirisson Island near Perth is called Matta-garup.

Nyungar people avoided venturing into deep murky waters, including upstream rivers and pools, as the dangerous bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas) was known to inhabit marine, estuarine and fresh water environments, especially in the Swan and Canning River system. Also known as the Swan River whaler, the bull shark can spend long periods of time in fresh water.

Towie (2013) based on advice from Dr Brett Molony (the W.A. Department of Fisheries supervising scientist) and Dr Fiona Valesini (Murdoch University Fish scientist) states that bull sharks may be present in upstream river systems, especially at certain times of the year when breeding. In the Swan River they may be found in the deeper waters between South Perth and Maylands where they mate and give birth in late spring and early summer.

Another shark expert Dr Jonathon Werry from Queensland states that bull sharks, which can grow to more than three metres long ‘usually stayed in deep holes and migrated across shallow zones in packs.’ He pointed out that juvenile bull sharks could jump up small waterfalls using strong thrusts of their tails. “It’s a feeding behaviour when they’re chasing fish, but it isn’t something that happens all the time.” He said they could target prey that was bigger than them when they reached about 1.5m long. Bull sharks can grow up to 3.5 metres and are known for their stocky shape, broad, flat snout and aggressive behaviour (ABC Sunshine Coast 2015).

The invisibility of the predatory bull shark in the murky waters of rivers and estuaries in the Perth region together with its close relative the dusky shark found in the Albany region and lower southwestern Australia may explain the stories passed down through the generations about the mysterious disappearance of Nyungar people. It is our opinion that these accounts, especially those involving children who disappeared from the vicinity of deep dark stretches of rivers and pools that were believed to be the haunts of the mythological Waugal, were probably bull shark or dusky shark- related fatalities. When human life is lost to an unseen predator, people will mythologize and attribute fearsome, dangerous and supernatural agency to the point where the shark becomes a menacing ghost or spirit.

We are curious as to why the Nyungar linguist Whitehurst (1992:16, 47) treats the term maadjit as synonymous with the term wakarl and translates maadjit as ‘water snake (spiritual).’ Could Whitehurst’s maadjit be the same water spirit as Ethel Hassell’s marget, an entity in some way analogous to the wakarl or other unseen and potentially dangerous water spirit? Both the wakarl (mythological snake) and maadjit (shark) may be viewed as awesome spirit shadows of deep dark pools and cloudy waters. We are by no means suggesting that the waugal and the shark are one and the same entity but rather that the term maadjit may be a descriptor referring to a powerful and malevolent water spirit, feared and revered by all.

The existence of freshwater and saltwater versions of the waugal (or wakarl) were brought to our attention by Ken Colbung (1991 personal communication) when he described the mythological track of the saltwater waugal from Two Rocks near Yanchep in the north to Cape Leeuwin in the south. When we asked him whether the saltwater waugal was a different type of waugal to the freshwater one, he said that

‘they were one and the same and that the waugal was the ‘spirit protector of all water.’

This would agree with the translation provided by the Nyungar Elder and linguist Cliff Humphries and recorded by Tim McCabe (1998: 185 in Thieberger 2004:38) of the term maardjet as “sea serpent.” It would seem that maadjit (or maardjet) with its saltwater and freshwater manifestations probably had a much deeper esoteric mythological meaning than its reference simply to shark.

Maadjit-teeyl – sacred shark stone

In Nyungar culture sharks were and still are held in awe and attributed great spiritual significance. Some traditional boylya gadak (shamans) were believed to possess ‘the magic stone of the shark’ known as maadjit-teeyl. This was a powerful ritual object used by the shaman to influence shark behaviour. Grey (1841) writes:

Maad-jit-teeyl – the magic stone of the shark – these are pieces of crystal supposed to possess supernatural powers; some of them are much more celebrated than others: none but the native sorcerers will touch them.’ (Grey 1840: 76)

Teeyl – any crystals, these are supposed to possess magic power, the same name is also applied to any thing transparent.’ (Grey 1840: 117)

Boylya men were reputed to control shark movements using these sacred stones together with sub-vocal magical incantations. Colbung (1993 pers. communication) believed that the bulya men who possessed these magic quartz crystals that (he believed) were shaped like the teeth of a shark had the power to transform themselves into a large shark and travel deep under the ocean to the land of the ancestors and bring back powerful magic and Law. He said ‘Sharks are not of this world. They are phantoms of the sea.’ These journeys may have been performed in dreams or altered states of consciousness brought on by focused meditation on the powers of these sacred stones.

Petri (2014) in his discussion of the Aboriginal medicine man’s symbols of magic and power highlights the symbolic significance of quartz crystals, the origins of which are often attributed to the ‘rainbow serpent’ or other powerful spirits of tribal mythology. He compares how the southeast Australian Aborigines trace the origin of quartz crystals ‘back to the supreme sky beings, the creator deities sitting on crystal thrones’ whereas the source of these sacred objects in coastal Nyungar culture is ‘attributed to the shark.’ Petri writes:

‘An idea, unique of its kind, about the origin of quartz crystals is reported to us by Moore from S.W. Australia in the days of the founding of the Swan River colony. The diaphanous stones, apparently very highly rated here by the Aborigines and called ma-djit-teyl (teyl according to Sir George Grey) are attributed to the shark’ (Petri 2014: 75).

It is unclear to us whether the term maadjit meaning “shark” was in general use throughout coastal southwestern Australia as implied by Grey (1840:76) who provides the only description of these sacred “shark stones” or whether they were only used along the southern coast. Moore (1842:47; 1884:65) alters the spelling to madjit-til, copies Grey’s descriptions and indicates these terms were confined to King George Sound but Von Brandenstein’s (1988) work shows that the term is also found in the Esperance region. What is clear is that there are a number of variant spellings of martiat (Nind 1831:33). These include maadjit (Grey 1840:76), madjit (Moore 1842:47), matchet (Neil 1845), magetup (A.Y. Hassell 1894), marget (Hassell 1880’s, 1975), majitt (Rae 1913), majjet (Bates 1914) and maar-tiurtt (Von Brandenstein 1979).

Grey (1840: 76) records maadjit as ‘a species of shark much dreaded by the natives’ and Moore (1842:47) records majit as ‘a species of shark.’ Interestingly, neither makes any attempt to ascribe it to a named species or category of shark. Neil (1845) records matchet as the Nyungar name for ‘the common blue shark of the settlers’ (Prionace glauca) and “the bull-dog shark’ of the sealers’, although he notes that the latter is also known as korluck or quorluck. A.Y. Hassell translates the term quorluck as meaning ‘teeth.’

Von Brandenstein (1988: 8, 11), a specialist in Nyungar linguistics, records maar-tiurtt or maatt-tiurtt as the name for ‘the white shark’ (Carcharodon carcharias), more commonly known as ‘the great white’ or ‘white pointer.’ He translates maar-tiurtt literally as ‘white hand’ (maar, hand + tiurtt, white) and maatt-tiurtt as ‘white leg’ (maatt, leg + tiurtt, white).

Douglas (1979) points out that ‘maat’ not only means leg but is also a metonym for ‘way’ or ‘path’ and ‘refers also to a particular sacred or totemic ‘path’ or ‘group.” The works of Bates (in White 1985), Von Brandenstein (1979, 1988) and Douglas (1979) note that ‘mat’ or ‘maat’ may denote ‘leg,’ ‘family,’ ‘lineage,’ ‘stock,’ ‘member,’ ‘mate,’ ‘tribe’ or ‘track.’

If the reader feels that they are getting lost at this point and wonders where all this is heading, Von Brandenstein’s (1988: 113) informant alludes to the sandy white or light coloured Tyiurtt being ‘the ancestral hero involved in the creation of the southern coastline.’ He provides no further details. Could the ‘white hand’ that Von Brandenstein (1988) describes be a body part metaphor for the prominent dorsal fin, as this would have been the only visible sign of the shark’s presence in the water?

This leaves us with the quandary of its white colour. Shark fins are dark-coloured. Was the creative ancestor the maatt-tiurtt perceived as white or light coloured having returned from the land of the dead? The returned human djanga or ghosts were always perceived to be white or light coloured? Could it be for this reason that the bulya men or shamans, as suggested by Colbung (1993, pers. communication), were able to transform themselves into their spirit-familiar (shark) and travel underwater to Kurannup (the place of departed spirits, place of ‘long time ago’) to seek powerful magic from the ancestors?

We disagree with Von Brandestein’s assignment of maatt-tiurtt to a single shark species – the great white. Our research suggests that it was a collective or general descriptor for shark and potentially other unseen creatures of deep, dark waters.

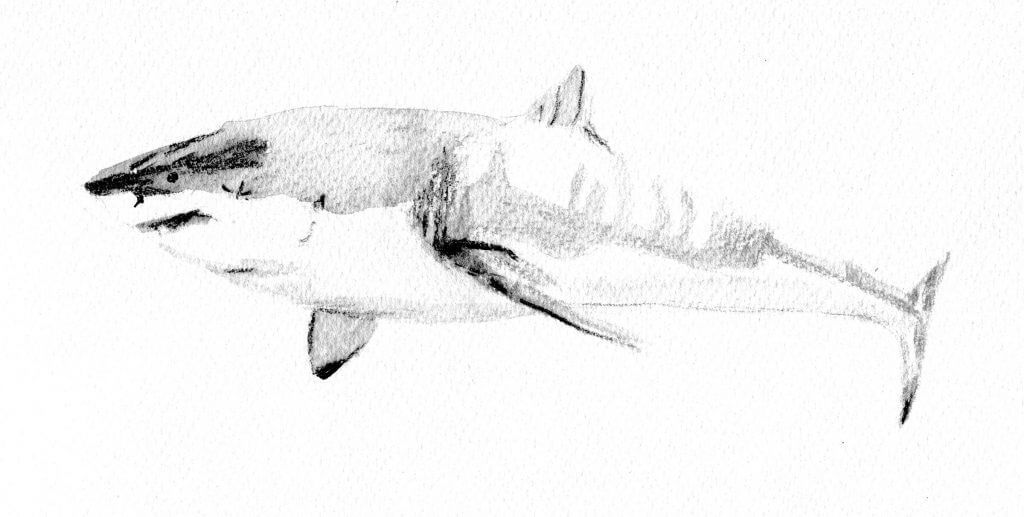

Shark (matchet) sightings as seasonal indicators of spawning salmon

Sharks of all kinds are attracted to schools of spawning salmon (see Figure 7). The blue shark or matchet was well known for its fish herding behaviour in temperate waters. Its herding behaviour is predictable and seasonal and dependent on the schooling and spawning cycles of migratory fish, such as salmon and mullet. Hutchins and Thompson (1983: 14) point out that this shark ‘rarely occurs in coastal waters because of its preference for oceanic conditions.’ However, the large aggregations of spawning salmon in inshore waters at King George Sound would have been an annual attraction for these migratory herders, as well as other sharks, and their presence indicated the arrival of the migratory salmon from South Australia.

Salmon were speared for their nutritious oily flesh during their spawning season. At King George Sound this ran from approximately February to April (see Collett Barker 1831). The sighting of shark fins (mar-git, lit. shark or shark tail, term recorded by King 1821) in offshore waters at this time of the year was a reliable indicator that the salmon spawning season known by the Minang (Nyungar) as meerteluk had commenced. Prior to this time spotters positioned themselves on high rocky vantage points along the coast waiting in anticipation for the salmon to arrive (Collett Barker 1831).

The boylya gadak (shaman) and keeper of ‘the magic stone of the shark’ (maad-jit-teeyl) probably possessed the shark as his totem. Using his specialized knowledge of shark movements and feeding behaviours he was perceived as being able to control by magical and supernatural means the fish-herding behavior of these particular sharks.

One Elder for the Esperance region interviewed by Ken Macintyre in the 1970’s stated that the shark was a totemic familiar of whoever possessed the sacred stones (Macintyre field notes 1973). The Elder referred to these men with the special powers as ‘shark whisperers.’ Shark and fish behaviour were well understood in indigenous ecological knowledge (IEK). There was no magic involved in the shark’s herding of salmon towards shore. It was all part of a feeding cycle: the sharks feeding on the spawning salmon, the spawning salmon feeding on the numerous bait fish (such as white bait and herring) and the Nyungar spearing and collecting large quantities of fat-rich salmon from the shallow waters. This was a cycle that recurred every year from the time of the Dreaming.

Another cycle of shark fish-herding behavior according to anecdotal evidence involved the mullet (or kalkarda). An Elder from the Pinjarra region told us that ‘the old people’ knew when the mullet would arrive because large sharks would drive schools of these fish towards the shore. He was referring to the Harvey River -Peel estuary but he said it no longer occurred because the inlet has changed and few people remember the stories.

Most coastal Aboriginal (or ‘saltwater people’ as some call themselves) valued and in many cases still value the shark as a spiritual totem and protector. This ethnographic fact is well documented for the Aboriginal people of Northern Australia (see the work of ethno-zoologist McDevitt 2005) but it is less well known about in southern Australia where, for example, the Ramindjeri people of South Australia had the shark as a totem and were forbidden to hunt it; the Aboriginal people of the Port Jackson area around Sydney greatly respected the shark as a totem and did not consume shark or any member of the ray family, and similarly the Nyungar people of southwestern Australia.

Moondo – the ghost of the sea

We have often wondered why Nyungar people did not eat shark or stingray as part of their diet when in other parts of Australia these cartilaginous fish were consumed with relish. Was it because of its strong ammonia smell and taste that made the shark unpalatable? Or was it the physical danger involved in hunting such a large predator with only a hand-held fishing spear (gidgigarbel). Or could it have been, as we have already mentioned, that the shark was no ordinary fish but a spirit from the other world deep under the ocean. We may never know, though there may well be a clue in the name moon-do, first recorded by Grey (1840: 87) as ‘a species of shark, which the natives do not eat.’

Symmons (1841:vi) and Moore (1842:57) record it as mundo referring to ‘Squalus; the shark. The natives do not eat this fish.’ Bussell (n.d.) spells the name as moonder. When translated, what does the term moon-do or munder possibly mean? Could it be that mundu means ‘ghost’ (as noted by Curr 1886) making it similar in meaning to the term madjit which, according to some sources, denotes a spiritual entity. Nyungar Elders from the Perth region believed that the term moonder is the local term for shark. Some attributed it to the tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvieri) while others used it as the general term for shark. Ken Colbung believed that moonder was the name of the tiger shark and suggested that it was the totem of the bulya-men of the Bibbulman-Waddarndi people and coastal ‘mobs.’ He explained how Moonderup (or Moondarup) meaning ‘place of the shark’ included the area of limestone cliffs, caves and waters along the coast at Mosman Park and Cottesloe.

Interestingly, Moore (1842: 14) records the name for shark in the Bunbury area as bugor. He writes: Bugor – ‘A Brave; one who does not fear. At Leschenault this is the name of the Mundo or shark.’ The shark’s top predatory status and fearlessness must surely have caused anxiety among local Nyungar fishers who regarded them with awe and respect and imbued them with supernatural powers. One Elder told us that bugor could also be used to describe a courageous Nyungar man who was of hero status and unafraid of anything.

One of the things that puzzles us is the reason as to why Nyungar people did not consume shark or ray despite their relative abundance in coastal waters. Moore (1841) makes an interesting comparison between the Aboriginal people of the Sydney region and those of southwestern Australia where he notes that:

‘They have an aversion to sharks and rays, and the same fish are equally rejected by the inhabitants of Sydney and the eastern coasts; though why they do so, is unexplained.’ (Moore 1841: 311)

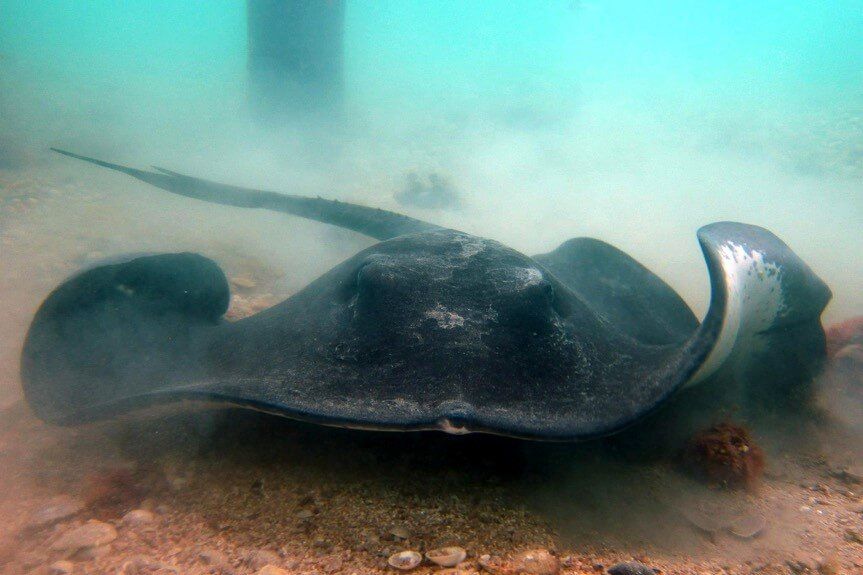

Bumber – Stingray

Nind, the resident medical practitioner at King George’s Sound between 1827 and 1829, observed that stingrays and maiden rays were ‘common’ in the sheltered bays, inlets and estuaries of the Albany region. Interestingly, when Captain Cook first visited Botany Bay he named it ‘Stingray Bay’ owing to the abundance of these fish.

Neil, writing in 1845, points out that the Aborigines of the Albany region ‘greatly abhor’ the stingray and do not eat it. He gives no explanation.

We surmise that the term bumber recorded for the stingray by Alfred Bussell (n.d.) is an expression of the aversion and revulsion felt towards this fish and that it derives from boom-boor-am-in which Grey (1840: 14, 13) translates as ‘aversion, hatred or rage.’

Another name for the stingray is poinjinon (Rae 1913). Neil (1845) records the “young sting-ray of the sealers” as kegetuck or bebil. This would seem to be a reference to the stingaree or round ray (Genus Urolophus). A.Y. Hassell (1894) records its Nyungar name as culbinyong (Bindon and Chadwick 1992: 394).

The shark-like ray known as the Southern Fiddler (Trygonorrhina fasciata (see Fig. 11) is known as parett (Neil 1845). This Nyungar name (also sometimes spelt paritt or parrit) is an alternative common name. Trigonorrhina derives its meaning from the Greek terms trygon meaning ‘stingray’ and rhinos meaning ‘nose. It is a member of the shovelnose ray family. In colonial times it was known by the early settlers as ‘green skate’ and by the sealers as ‘fiddler.’’ Neil (1845) describes it as:

‘Very common in the sheltered bays, close inshore among the weeds. Not eaten by the Aborigines, who greatly abhor them, as they do also the sting-ray.’ (Neil 1845)

The Nyungar name parett possibly derives from barrit meaning ‘deceit, deception,’ referring to the fiddler’s cunning camouflage disguise as it lies half buried in the sandy shallows or rocky bottom.

We could find no explanation in the literature as to why Nyungar people traditionally had such a cultural abhorrence to members of the ray family. Could the reason be that stingrays are dangerous creatures capable of inflicting extreme pain and potentially life threatening injuries on their human victims? They have sharp, serrated barbed spikes on their tails that are poisonous and used in self defence. The sudden whip-like action of their armed tail can cause serious wounds leading to blood loss and, if untreated, can cause death from infection or physical disablement from severed nerves or tendons.

The revulsion to consuming stingray flesh may have been a secondary explanation. We propose that Nyungar people had a highly developed olfactory sensory awareness that enabled them to detect harmful as well as beneficial environmental odours. At one time in prehistory contaminated stingray flesh was probably eaten causing serious illness and possibly death, and the unpleasant ammonia-like smell of contaminated meat would have registered in their olfactory consciousness as having harmful consequences. Over time the smell of ammonia would have become a culturally ingrained cue to avoid flesh tainted with this fetor. This olfactory survival mechanism would have become a cultural adaptation over time. Moore (1841: 311) reinforces this idea by stating that they only eat their meat ‘whilst fresh, and will not touch tainted meat.’

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

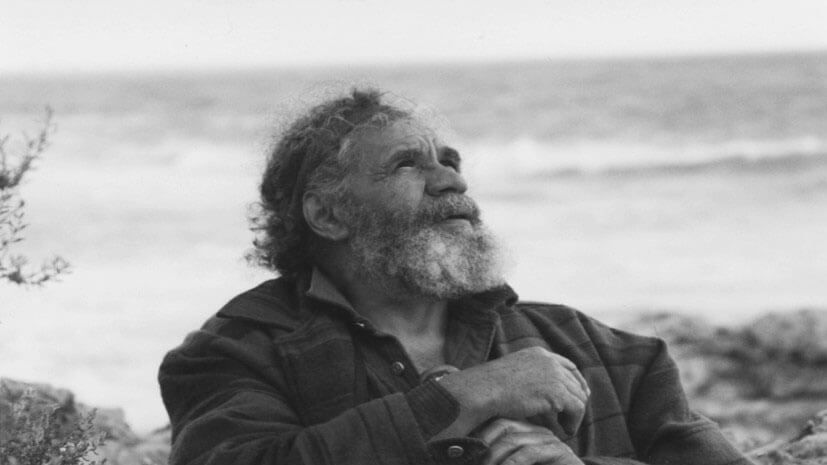

This paper was prepared by research anthropologists Ken Macintyre and Dr Barb Dobson using ethno-historical sources and contemporary information provided by Nyungar people interviewed between 1990 and 2013. We would like to thank all the Nyungar Elders, especially (the late) Ken Colbung for his knowledge and enthusiasm in providing a Bibbulmun (Nyungar) perspective on the coastal marine habitat. Without Ken’s help this paper on sharks would have been incomplete.

Our interpretations of the ethno-historical sources may be inconsistent with the views of some contemporary Nyungar people.

BIBILOGRAPHY

ABC Sunshine coast 2015 ‘Seven bull sharks caught on video hunting in landlocked Sunshine Coast canal.’ http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-12-04/seven-bull-sharks-in-suncoast-canal/7001450

Appleyard,S.J., Macintyre, K. and B. Dobson 2001 “Protecting ‘Living Water’: involving Western Australian Aboriginal communities in the management of groundwater quality issues”. Paper presented at the International Groundwater Management Conference, University of Sheffield, England. April.

Armstrong, F. 1836 ‘Manners and Habits of the Aborigines of Western Australia, from information collected by Mr F. Armstrong, Interpreter.’ The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal 29/10/1836, 5/11/1836 and 12/11/1836.

Bates, D. 1938 The Passing of the Aborigines: A Lifetime spent among the Natives of Australia. London: John Murray.

Bates, D. 1914 ‘A Few Notes on Some South-Western Australian Dialects’ The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 44 (Jan-June) pp. 65-82.

Bates, D. 1985 The Native Tribes of Western Australia. Isobel White (Ed.). Canberra: National Library of Australia,

Bates, Daisy 1992 Aboriginal Perth: Bibbulmun Biographies and Legends. Peter J. Bridge (Ed.) Carlisle, Perth: Hesperian Press.

Bindon, P. and Chadwick, R. (eds.) 1992 A Nyoongar Wordlist from the South-West of Western Australia. WA Museum, Anthropology Department.

Brough Smyth, R. 1878 The Aborigines of Victoria. 2 vols. Melbourne and London.

Browne, James 1836-1838 Aborigines of the King George Sound Region: the collected works of James Browne. Compiled and edited by anthropologists Ken Macintyre and Barbara Dobson. Victoria Park, Perth: Hesperian Press.

Bunbury, H.W. 1930 ‘Early Days in Western Australia.’ London: Oxford University Press.

Bussell, A.J. n.d. Southwest Aboriginal language or dialect, the Aboriginal’s term ‘Dordenup Wongie’ andother things concerning Australia generally. Busselton Historical Society.

Colbung, Ken 1991, 1992,1993, 1997, 1999, 2000, 2001 Personal communication over many years.

Collet Barker, Journal 13th September 1828-29 August 1829. Microfilm, Viewed at the Battye Library. Perth. Original copy held at the State Library of New South Wales.

Collie 1834 ‘Anecdotes and Remarks relative to the Aborigines at King George’s Sound (from an original manuscript by a resident at King George’s Sound).’ Published in the Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal July-August 1834. Attributed to Dr Alexander Collie in Neville Green (ed.) 1979 Nyungar – The People: Aboriginal Customs in the southwest of Australia. Perth: Creative Research Publishers.

Curr, E.M. The Australian Race: Its origin, languages, customs, place of landing in Australia, and the routes by which it spread itself over that continent. Vols 1 & 11. Melbourne: Government Printer.

Dench, A. 1994 ‘Nyungar’ in Thieberger, N. and W. McGregor Macquarie Aboriginal Words. Macquarie University, N.S.W.

Douglas, Wilfred H. 1976 The Aboriginal Languages of the South-West of Australia. 2nd edition. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aborginall Studies. RRS 9.

Ffarington Folio 1843-1847 S.W. Australia. Art Gallery of Western Australia. Sketch by Richard Atherton Ffarington of a Nyungar man fishing from tree by river in the southwest.

Green, N. 1979 (Ed.) Nyungar – The People: Aboriginal customs in the southwest of Australia. Mt Lawley, North Perth: Creative Research Publishers.

Grey, G. 1840 A Vocabulary of the Dialects of Southwestern Australia. 2nd edition. London: T & W Boone.

Grey, G. 1841 Journals of Two Expeditions of Discovery in North-West and Western Australia during the years 1837, 38 and 39. Volume 1.

Hammond, J.E. 1980, Winjan’s People: The story of the South-West Australian Aborigines, Hesperian Press, Victoria Park.

Hassell, A.Y. 1894 Notes and Family Papers. Battye Library. Perth

Hassell, E.A. 1880-1890’s Notes and family papers. Perth: Battye Library. Handwritten manuscript.

Hassell, Ethel 1975 My Dusky Friends: Aboriginal life, customs and legends and glimpses of station life at Jarramungup in the 1880’s. East Fremantle: C.W. Hassell.

Hordern, Marsden C. 1997 King of the Australian Coast: The Work of Phillip Parker King in the Mermaid and Bathurst 1817-1822. Melbourne: The Miegunyah Press. Chapter 18 ‘Meeting the Minang.’

Humphries, Cliff. (1998) and Tim McCabe (n.d.) a set of audio language tapes recorded by McCabe between 1996 and 1998 with Nyungar Elder Cliff Humphries, ms.

Hutchins, B. and M. Thompson 1983 The Marine and Estuarine Fishes of South-western Australia: A Field Guide for Anglers and Divers. Western Australian Museum. Perth.

Isaacs, S. n.d. Native Vocabulary. Perth: Landgate, (typescript)

King, P. P. (1827). Narrative of a survey of the inter-tropical and western coasts of Australia. London: J.Murray.

Landor, E.W. 1847 The Bushman or Life in a New Country. London: Richard Bentley.

Lyon, R.M. 1833 ‘A Glance at the Manners, and Language of the Aboriginal Inhabitants of Western Australia; with a short vocabulary’. In N. Green (Ed.) Nyungar – The People: Aboriginal customs in the southwest of Australia. North Perth: Creative Research Publishers.

Macintyre, Ken 1973 Field notes (unpublished).

Macintyre, Ken 1975 Field notes (unpublished).

Macintyre, Ken 1993 Field notes: consultations with Aboriginal Elders from the Perth-Pinjarra area. (unpublished)

Macintyre, K. 2004 Aborigines and the Cottesloe Coast. Paper presented at the Cottesloe Fish Habitat Protection Area Seminar sponsored by Coastcare, May.

Macintyre, K. and B. Dobson 2010 ‘Notes on traditional Nyungar taxonomy and nomenclature’ (forthcoming).

Madden, R.R. 1848 Vocabulary of the Aborigines, Perth Tribe Dialect (microfilm). Battye Library, Perth, Western Australia.

McDavitt, Matthew T. 2005 The cultural significance of sharks and rays in Aboriginal societies across Australia’s top end. Seaweek, March. http://www.mesa.edu.au/seaweek2005/pdf_senior/is08.pdf

Meagher, S. J. 1974 The Food Resources of the Aborigines of the Southwest of Western Australia. Records of the Western Australian Museum, 3:14-65.

Moore, G.F. 1841 ‘Aborigines of Australia – Swan River.’ The Colonial Magazine and Commercial Maritime Journal, 5, 19 (May) pp. 309-315. Ferguson Project Home Page, Australian Cooperative Digitization Project.

Moore, G.F. 1842 A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Language in Common Use Amongst the Aborigines of Western Australia. London: Orr.

Moore, G.F. 1884. Diary of Ten Years of Eventful Life of an Early Settler in Western Australia. London: M. Walbrook.

Mulvaney, John and Neville Green 1992 Commandant of Solitude: The Journals of Captain Collett Barker 1828-1831. Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press at the Miegunyah Press.

Neil, R. 1845 ‘Catalogue of Reptiles and Fish, Found at King George’s Sound.’ Appendix in E.J. Eyre Journals of expeditions of discovery into Central Australia, and overland from Adelaide to King George’s Sound, in the years 1840-1.

Nind, Scott 1831 Description of the Natives of King George’s Sound (Swan River Colony) and adjoining country. The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, Vol 1, pp. 21-51. Written by Mr Scott Nind, and communicated by R.Brown Esq. Read 14th February.

Petri, Helmut 2014 The Australian Medicine Man. Edited by Kim Akerman. Victoria Park, WA: Hepserian Press.

Rae, W. J. 1913 Native Vocabulary. Landgate. Perth (typescript)

Redman, Geoff 2015 ‘Bull shark pack in sunshine coast canal’ http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-12-04/bull-sharks-suncoast/7001460

Roe, J.S. 1835 ‘Journal of an Expedition from King Georges Sound, overland to Swan River, via York.’ In Shoobert, J. 2005 Western Australian Exploration, 1826-1835 Vol 1. Victoria Park, Perth: Hesperian Press.

Salvado, R. 1851 in E.J. Storman 1977 The Salvado Memoirs. Nedlands: University of Western Australia Press.

Shoobert (ed.) 2005 Western Australian Exploration 1826-1835, The Letters, Reports & Journals of Exploration and Discovery in Western Australia. Vol 1, Victoria Park, WA: Hesperian Press.

Stormon E. J. 1977 The Salvado Memoirs. Nedlands: University of WA Press.

Symmons,C. (1841) ‘Grammatical Introduction to the study of the Aboriginal language of Western Australia ‘ Appendix to C. Macfaull (ed.) The Western Australian Almanack.

Thieberger, N. and W. McGregor 1994 Macquarie Aboriginal Words. Macquarie University, Sydney: The Macquarie Library Pty Ltd.

Thieberger, N. 2004 Linguistic Report on the Single Noongar Native Title Claim. Unpublished. http://hdl.handle.net/11343/27658

Towie, Narelle 2013 ‘Bull sharks use Swan River for Birthing’ WA Today Nov 28.

Von Brandenstein, C.G. 1988 Nyungar Anew: Phonology, text samples and etymological and historical, 1500-word vocabulary of an artificially re-created Aboriginal language in the south-west of Australia. Pacific Linguistics Series C – No. 99. Canberra: Australian National University.

Von Hugel, Baron Charles New Holland Journal, November 1833- October 1834. Translated and edited by Dymphna Clark. Melbourne University Press in association with the State Library of New South Wales.

White, I. (Ed.) 1985 The Native Tribes of Western Australia. Canberra: National Library of Australia.

Whitehurst, Rosemary 1992 Noongar Dictionary: Noongar to English and English to Noongar. Compiled by Rosemary Whitehurst. First Edition. Bunbury: Noongar Language and Culture Centre.