The Puzzle of the Bardi Grub in Nyungar Culture

Ken Macintyre and Barb Dobson

Research anthropologists

Overview

The writings of colonial recorders have often misrepresented Aboriginal people as deriving most of their food from the hunting of large game (kangaroo, wallaby, emu) when in fact the bulk of their diet (around 80%) was based on vegetable foods and small game, for example, lizards, goannas, snakes, insect larvae, rodents and small marsupials many of which are now endangered or extinct. Grub eating was looked down upon by Westerners as an aberrant, opportunistic and almost degenerate means of human survival. This practice, like other unfamiliar food traditions such as indigenous geophagy (earth-eating) that we have described in a separate paper http://anthropologyfromtheshed.com/project/geophagy-the-earth-eaters-of-lower-southwestern-australia/only reinforced the colonial idea that the Aborigines of southwestern Australia, like those in other parts of Australia, were subhuman, uncivilized and deserved to be colonised by the economically, culturally and technologically superior ‘civilized’ white people. Little did the colonial superiors realize that traditional Nyungar knowledge of environmental, botanical, biological, phenological, ecological and entomological phenomena was heavily steeped in science and mythology and that this could have become a valuable asset to the colonizers had they wished to avail themselves of this knowledge.

Nyungar people used a range of environmental and astronomical indicators for predicting weather, seasonality, animal breeding patterns, movements and so on. They understood how humans, animals, plants and all of life were interconnected and this awareness was manifest in their complicated web of kinship and totemistic affiliations, rituals and mythology. Even anthropology graduates often have great difficulty comprehending the intricacies of these classificatory totemic kin relationships that bonded humans to their natural world. Indigenous mythologies most of which were not recorded by the white settlers owing to them being considered too incredulous (Grey 1841 acknowledges this) contained cultural metaphors, moral messages and deeply encoded ecological and animal, plant and bird phenological information. The traditional ecological and phenological knowledge held by Nyungar people at the time of European contact was a rich but, sadly, overlooked source of scientific wisdom that had evolved over many tens of thousands of years of empirical observation and experience. By not listening to these people and assuming them to have been technologically, culturally and socially inferior to the white colonisers, has meant the loss of an encyclopedic library of ecological knowledge that nowadays, with the rapid extinction of species in southwestern Australia, we shall never get back.

What is the bardi?

‘Our mob used to find good eating grubs in the blackboy, gum tree and wattle.

We been eating bardi since the Dreamtime. The old people knew when to find them. After the first rains. Better than beef they reckoned.’ (Greg Garlett, Nyungar Elder 2000)

As anthropologists we have often been confused by the use of the indigenous terms bardi and witchetty used to describe edible grubs in Australia. These terms are often used interchangeably to the point where bardi becomes defined as a witjuti grub and vice versa. How confusing is that? Both have become part of a lingua franca throughout Australia. When we tried to unravel the difference between a bardi and witjuti grub by asking some Nyungar Elders, they told us that a bardi is a type of witjuti grub. And maybe they are right.

Linguistic dictionaries and scholarly sources provide contradictory interpretations of the meaning of the term bardi (also rendered in ethno-historical sources as bardie, bardee, bardy, bader, bada, berda, paarde-paattt, barit, bert, and burrtt).1 Some say it is the larva of a longhorn beetle known as Bardistus cibarius belonging to the Cerambycidae family; others attribute it to the cockchafer larva of a scarab beetle (Scarabaeidae family); others to the larva of a buprestid jewel beetle from the Buprestidae family and others include as bardi the caterpillar larvae of moths, such as the hepialid rain moth Trictena atripalpis.2 The Buprestidae, Scarabaidae and Cerambycidae (all of which belong to the Order Coleoptera) represent three different Linnaean families of beetle, and some or all of these larvae found in southwestern Australia may be bardi.

We need to stop and ask ourselves are these Western scientific categories of ‘species’ and ‘families’ culturally relevant to a non-Western indigenous grub taxonomy? Maybe some answers will come to light in this paper.

Australian linguists Dixon et al (2006: 101-102) point out that the term bardi /badi/ is ‘chiefly used in Western Australia and South Australia’ and they acknowledge its Nyungar origins. They define bardi as:

‘The edible larva or pupa of the beetle Bardistus cibarius, or of any of several species of moth, especially Trictena atripalpis (formerly Trictena argentata). The beetle larva bores into the stems of grass-trees, eucalypts and acacias, and the moth larva is found underground, feeding on roots of eucalpts and acacias. The name is also applied to Abantiades marcidus. Also called bardi grub.’

While it would seem that bardi refers to a range of beetle and moth larvae, the ‘purists’ identify it to the immature form (larva) of the longhorn cerambycid beetle called Bardistus cibarius – this being the Linnaean species to which it was originally assigned in 1841 by the British taxonomist Edward Newman, based on an adult specimen provided to him by Captain George Grey from the Swan River Colony collected at King George Sound. 3

Yen (2010) a prominent scientist of invertebrates who has conducted extensive research on edible grubs in many parts of the world, including some Australian Aboriginal groups, categorically states that the term bardi should only be used to refer to beetle larvae and strictly to the larva of the buprestid beetle found in Xanthorrhoea. He states:

‘The name bardi grubs is based on a buprestid beetle from Xanthorrhoea in southwestern Western Australia, but has also been loosely applied to edible grubs across Australia.’ (Yen 2010:67)

‘…the guide for the official common names of Australian insects (Naumann 1993) lists three taxa of insects as bardi grubs: the hepialid moths Trictena atripalpis and Abantiades marcidus and cerambycid beetles; the term should only be applied to beetle larvae and strictly to the buprestid Bardistus cibarius (Yen 2005).’ (Yen 2010: 75-76)

In a later work Yen (2014: 80) refers to the bardi grub as the larva of “the cerambycid beetle Bardistus cibarius.” We are not entomologists so the task of putting a Linnaean-classificatory label on the bardi is beyond our scope. It would seem that even the experts do not agree as to its exact Linnaean identity. We have searched high and low to find a photo of the Bardistus cibarius larva to help shed light on its enigmatic identity but we could not find a single named image of this particular beetle larva. There are photos of the adult beetle Bardistus cibarius (see Plate 5) but not its larvae because Linnaean taxonomy relies exclusively on adult specimens to identify the subtle differences between species. The remarkably similar overall appearance of many beetle larvae despite their different species, genera or families, makes it impossible for non-entomologists to determine which Linnaean species they belong to. To us, they all look the same.

Even the entomologists Sreedevi and Verghese (2014:3-4) note that the larval forms of Buprestid and Cerambycid beetles look alike and confusing in the field. They state:

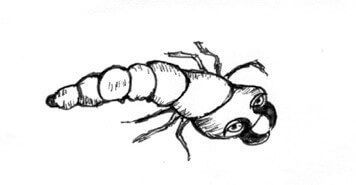

‘The larvae of the both groups are fleshy, white to greyish in colour, straight (not ‘C’ shaped), legless and taper gradually from anterior to posterior with dark, hardened and well developed mandibles. The Cerambycids are normally called as round headed borer and Buprestids are flat headed borer and as the name indicates, the larvae of both can be differentiated by shape of the head primarily (Figs. 1-2). The colour of the Cerambycids will be fleshy white while Buprestids larvae ranges from dull white to greyish.’

Cerambycid larvae have also been described as ‘white to yellowish in colour with a soft body, small head and strong jaws, an enlarged thoracic segment and a body that tapers towards the tail with legs small or absent’ (Comstock and Comstock 1901; Hangay and Zborowski 2010 cited in Seaton 2012:12). In cool temperate zones the cerambycid life cycle may last from two to three years, most of that time spent in the larval stage inside the host plant. Yen (2014: 86) notes that longhorn beetle larvae are consumed in many cultures including New Zealand (known as “huhu”), Tonga, Fiji and Samoa.

Another type of beetle larva consumed by Nyungar people is the cockchafer. This is found in abundance in the trunks of Xanthorrhoea at the proper season (see Plates 1-2). Nind (1831) records its name as paaluck which is also the name of its habitat provider – the decaying or dead Xanthorrhoea (called paaluc). Cockchafers are the larvae of scarab beetles. They are characteristically C-shaped when feeding or at rest and referred to as ‘white grubs’ or ‘curl grubs’ because they:

‘curl up into a ball when disturbed. They are creamy white in colour with a prominent head (which differs in colour with different species) and three pairs of well-developed thoracic legs. There are no abdominal legs. The rear part of the abdomen is often dark grey in colour as a result of the gut contents showing through the body wall.’ (Phillips 1993).

‘Grubs are whitish to cream-colored with a brown head and three pairs of short legs. White grubs are soft bodies and exhibit a characteristic C-shape posture when feeding or at rest.’ (Frank 2015)

Some or all of these cerambycid, buprestid and cockchafer larvae may be bardi, if the term is applied generally.

Colonial revulsion to the idea of grub-eating

To begin our journey in search of the bardi we must turn to the earliest accounts of indigenous entomophagy (insect-eating) in southwestern Australia. The following comments illustrate how the early 19th century colonial writers observed this practice with a degree of revulsion.

In 1829 Dr T.B. Wilson describes his awkward encounter involving the exchange of food items with some Aborigines of the Perth-Canning River area whereby he states:

‘One of them, who appeared to be superior to the others, both in rank and intelligence, shewed us various roots which they used for food, and also the manner of digging for them; and, in return for our civility, in giving him and his friends a little biscuit, he procured a handful of loathsome-looking grubs from a grass-tree, and offered them to us, after having himself ate two or three, to show us that they were used by them as food. His polite offer being courteously declined, he snapped them up, one by one, smacking his lips, to show us that what we had refused was esteemed, by him, as a “bonne bouche.” 4 (Wilson 1829 in Shoobert 2005: 93)

Captain George Grey (1841: 289-290) compares in a cross-cultural manner the settler’s revulsion to the eating of grubs with the indigenous people’s cultural abhorrence of the European consumption of raw oysters. He comments:

‘Grubs are either eaten raw or roasted; they are best roasted tied up in a piece of bark, in the manner that I have before stated that they cook their fish. If the natives are taunted with eating such a disgusting species of food as these grubs appear to Europeans, they invariably retort by accusing us of eating raw oysters, which they regard with perfect horror.’

This Anglo-European attitude of disgust and revulsion at the thought (far less the reality) of eating insect larvae continues in many respects to the present day. Where did this cultural aversion to eating grubs come from? Is it part of a cultural mindset that we have that associates grubs, maggots and worms with dirt, disease and decay? Is this why we shudder at the thought of a grub burger or a maggot omelette? Hunger is another factor in this equation that we should not overlook. How many of us have ever really suffered the pangs of hunger and the possibility of starvation? If so, these protein and fat rich grubs might look different.

The eating of bardi, or witjuti as it is more commonly known nowadays, is seen by many as a culturally risqué activity, a bit similar to the Western repugnance to eating raw fish (Japanese style sashimi) in Western Australia in the early 1970’s. But has our repugnance towards grub eating always been the case? An article in the Western Mail in 1924 describes white settlers in southwestern Australia eating with relish the caterpillar larvae of the wood-boring moth, called by them ‘the bardie moth.’ Drawing on information from the Government Entomologist of the time, the report states:

‘The caterpillars, people call them grubs, are known by the natives in some places as “bardies,” and are considered by them to be a delicious morsel, as much appreciated as an oyster by an epicure. The love for bardies is not confined to the black-fellow, because many settlers, having tasted toasted bardies with caution, have come to relish them, and there is no reason why they should not be quite as wholesome and as nutritious as any other delicate vegetable feeding animal.’ (Western Mail 1924).

In an article in the Mirror in 1936 the Curator of the WA Museum Mr Glauert describes the bardi as “a delectable savoury served on toast.’ These anecdotal accounts testify to the flavoursome taste of bardies, whether they are toasted or served on toast. Another newspaper article in 1950 notes that bardie tasting ‘became a craze among visitors’ to the Wildlife Show held in Perth to the point where supplies almost ran out. It says ‘Show officials have now gone in search of more bardies to satisfy the new public taste.’

The prominent local naturalist of the time Vincent Serventy provides culinary insight into bardies: ‘Most people want them roasted – it must be psychological, as they’re really just as nice raw.’ ‘He said that when Aborigines roasted bardies they lit a fire on a flat rock, waited until the rock was really hot, then brushed off the ashes and used it as a stove.’ (The Argus 21st September 1950).

Grey (1841: 276, 289) describes how barde grubs were often ‘roasted tied up in a piece of bark’ in the same way that they cooked fish, including whitebait. This method was called “Yudarn dookoon,” or “tying-up cooking.” He states:

‘A piece of thick and tender paper bark is selected, and torn into an oblong form; the fish [grub] is laid in this, and the bark wrapt round it, as paper is folded round a cutlet; strings formed of grass are then wound tightly about the bark and fish [grub], which is then slowly baked in heated sand, covered with hot ashes; when it is completed, the bark is opened, and serves as a dish; it is of course full of juice and gravy, not a drop of which has escaped.’

As early as 1842 F.W. Hope proposed, with reference to the white grubs or cockchafers of the scarab beetle – the ‘larvae eaten by the New Hollanders and in some other parts of Australia’ – that these might one day become a gourmet food.5 He writes:

‘[should] the food prove palatable and wholesome, the settler, from policy, should patronize as food these dainties which are so highly prized by the wild Australian, and thereby secure the crops of future years by feeding on the insects capable of destroying them; and certainly no reason can be adduced why the grubs of New Holland may not rival in delicacy the palm-worm of the Eastern World, or the cossus of Europe, which the Roman epicure, in the days of Pliny, so highly esteemed.’

Nyungar names for edible grubs

There are over 15 different Nyungar names for mostly undetermined edible grubs. These are the barde (or bardi, bardie, bardee, badee, bader, bada, berda, barit, bert, burrtt, paarde-paattt), boo-yit, boodjark (or budjark), paaluk (or paluk), changut, woolgang (or wulgang), iular, kurrang (or gurang, cooranga), pari (or pere), nargagli, wandona, (or wandunu), marn-duk (or mundark), bejenup, marign, marnung and mutarnuk. 6

Most of these are “descriptors” that convey information about the habitat, ecological indicators, life cycle stage, seasonality, means of procurement and nutrient content of these larval foods.7 In traditional taxonomy and nomenclature the same animal (or plant) may have a number of different names, depending on which aspect or product is being described, for what purpose and at what season. These indigenous descriptors had a practical, utilitarian and survival value and were sometimes mythological referents that encoded a cultural narrative into a mnemonic term or phrase.8

bader, barde, bardi – edible grub

In 1836 Lieutenant Bunbury records the name for the ‘grass tree grubs’ as bader (Bunbury in Cameron and Barnes 2013:137) or bada (Bunbury 1930:198). This is the very first appearance in print in Australia of the original version of the term bardi.9

Bunbury (1930:198) also records nargagli as the name of the “blackboy grub” among Nyungar people living to the south of Perth in the Murray River area. We would suggest nargagli is a food descriptor signifying that ‘eating bardi makes you strong.’ Our reasoning is that Grey (1840: 98, 87) records narr-gallia as meaning ‘moor-doo-een nalgo’ and moor-doo-een literally translates as ‘strong, powerful’ and nalgo ‘to eat’ (Grey 1840; Bunbury 1930: 198), hence implying ‘strong, powerful to eat.’ The term nargagli may also be a variant of narkergery which Curr (1886) translates as ‘food,’ in this context meaning a high-energy food, rich in fat.10

Several years later Grey (1840: 7) records the name of the edible grub found in the Xanthorrhoea (grass tree) as barde and Moore (1842) spells it as bardi. Regional variant spellings of this term include burrtt (Gray 1987) and ‘bardi, berda or bert’ (Dench 1994: 185). A.Y. Hassell records barit as the name of the large edible grub found in wattle. Whether this is a variant rendition of burrtt or bert is unclear. Salvado (1851) records edible grub as pari. This is not too different from Hassell’s barit (for “b” and “p” sounds in Nyungar language are considered interchangeable when rendered into written form). Curr (1886) translates baring to mean fat. Could these terms be descriptors referring to the nutritive fat content of these highly prized grubs? We think so.

Grey’s “barde”

It was not until Grey (1840:7) came on the scene that the indigenous method of collection and consumption of barde is mentioned. He describes it as follows:

‘barde – a white grub found in the Xanthorrea. These grubs have a fragrant aromatic flavour, and form a favorite article of food amongst the natives. They are eaten either raw or roasted, and frequently form a sort of dessert after native repasts. The presence of these grubs in a grass tree is thus ascertained. If the top of one of these trees is observed to be dead, the natives give it a few sharp kicks with their feet, when, if it contains any barde, it begins to give; if this takes place, they push it over, and breaking the tree to pieces with their hammers, extract the barde.’ (1840: 7)

Further information is contained in Grey’s 1841 journal:

‘Grubs are principally procured by the natives from the Xanthorrea or grass-tree, but they are also found in wattle-trees, and in dead timber; those found in the grass-tree have a fragrant aromatic flavor, and taste very like a nice nut. (Grey 1841: 288).

…he extracts the grubs, of which sometimes more than a hundred are found in a single tree. (Grey 1841: 288)

‘King George’s Sound, where it seems to be very abundant, forming a favourite article of food with the natives who call it Barde; it is eaten in its imago as well as its larva and pupa states.” (Grey 1841: 466)

Grey (1840, 1841) was not satisfied with merely observing and describing the barde but was intent on providing it with a Linnaean classification. To achieve this end he collected an adult beetle specimen from King George Sound and presented it to the British Museum for identification by Edward Newman, the prominent entomologist and botanist. The taxonomic description of the imago named Bardistus cibarius was communicated to Grey via a letter from Adam White, Esq. British Museum as follows:

‘Of a yellowish bay colour, the head, thorax, and basal part of the three first joints of the antennae darker; the elytra soft, margined, with three parallel raised lines, not reaching the tip, the outer is on the side and not so distinct as the other two; there is also a short one running from the base of the elytron near the scutellum, and soon forming a margin to the suture. The antennae are slightly hairy outside. (In the accompanying figure* they are much too short.) There are a few short hairs at the rounded tip of the elytra.’ (White in Grey 1841: 465)

The Genus name Bardistus is a Latinized version of the Nyungar term bardi. We do not understand why Grey chose this particular longhorn beetle to be the barde type specimen, especially when barde grubs from the Xanthorrhoea (grass tree) and Acacia (wattle) would have included a variety of beetle and moth larvae as the Xanthorrhoea relies on insect-pollinators. The appendices in Grey’s Journals (1841) confirm that he collected a variety of coleopterous (beetle) specimens from King George Sound, and a range of large moths, all of which larvae may have potentially been viewed from an indigenous (or what anthropologists call an emic perspective) as barde.

Grey’s (1841) quest for an individual species’ name has unwittingly resulted in much confusion and disputation over the years as to the true identity of the bardi grub. His wordlist and journals soon after publication became highly popular throughout Australia and were influential in shaping perceptions of indigenous life and terminology.

Even to this day Grey’s works are considered seminal to an understanding of Nyungar culture as it was at the time of European contact. His accounts are generally taken at face value as if based on scientific or ethnographic reality when like his contemporaries they were often an admixture of personal experience, observation, colonial hearsay, newspaper accounts and other explorers’ recollections.

There is no doubt in our minds that the term bardi originates from the Nyungar language, having first appeared in print in 1836 as bader in Bunbury’s journal. Grey (1840) records it as barde and Moore (1842) as bardi. The term rendered as “bardy” in Australian-English (see Ten Raa 1973: 13 and Dench 1994: 185) has become a lingua franca in many indigenous languages of southwestern, western, southern and central Australia where its variant spellings include bada, barde, bader, berda, bardi, barti burrt, bert, barit, pardi, pati, pari and paarde-paatt. 11

The bardi of Grey’s contemporaries

George Fletcher Moore, a contemporary of George Grey’s, also compiled and published a descriptive vocabulary. This in many respects mirrors Grey’s work, although changing the orthographic renditions of words and adding an English-Nyungar component to make it more accessible and useful to English-speakers. Moore’s description of bardi is almost identical to that of Grey’s barde:

‘bardi – The edible grub found in trees. Those taken from the Xanthorea or grass-tree, and the wattle-tree, have a fragrant aromatic flavour, and form a favourite food among the natives, either raw or roasted. The presence of these grubs in a Xanthorea is thus ascertained: if the top of one of these trees is observed to be dead, and it contains any Bardi, a few sharp kicks given to it with the foot will cause it to crack and shake, when it is pushed over and the grub extracted, by breaking the tree to pieces with a hammer. The Bardi of the Xanthorea are small, and found together in great numbers; those of the Wattle are cream-coloured, as long and thick as a man’s finger, and are found singly.’ (Moore 1842: 5)

What Moore’s statement tells us is that bardi is a general term for the large and small grubs found in grass trees and wattles. He makes a brief reference to the cream-coloured wattle tree bardi but does not mention the white colour of the smaller grass tree grubs as noted earlier by Nind (1831) and Grey (1840). In one of his earlier publications Moore (1841) refers to, but unfortunately does not give the name for:

‘a sort of marrow-like grub, which they get from trees, & the taste of which varies, according to the substance upon which it feeds, and the tree from which it is taken. …Those from the zanthorrheas [Xanthorrhoea] have the flavour of chestnut; they are found in abundance under the bark of a genus [of] eucalyptus, when first beginning to decay; but these have an astringent taste. They are also found in the jacksonias and the acacias.’

Drummond (1839), the colonial botanist, makes a fleeting reference to the edible larvae found in Xanthorrhoea. He writes:

‘One of the most striking plants to a stranger is our common Blackboy a fine arborescent species of Xanthorrhoea, growing from 10-15 feet high, with a trunk about a foot in diameter, and a flower stalk almost as high as the plant itself…The spot where the town of Fremantle now stands was originally a grove of this Xanthorrhoea called here Blackboys, but which now get scarce in the neighborhood of settlements from the number used as firewood. The genus is of very slow growth, the largest specimens must be several hundred years old: these furnish the natives with a favourite article of food in the larvae of a large brown species of Cerambyx.’

We do not understand why Drummond (1843) did not acknowledge the Nyungar name for these larvae or make reference to the newly recorded Linnaean name Bardistus cibarius for by the time of his writing Grey’s (1840, 1841) wordlists and published journals would have been well read and discussed by the colonial literati.

We also wonder why Moore did not mention the Linnaean genus and species name for bardi in either of his wordlists (1842, 1884). Contemporary researchers, such as Meagher (1974), show no hesitation in assigning Moore’s bardi to Bardistus cibarius.

From our understanding, it would seem that what Grey has done in a genuine attempt to be scientifically accurate is to take a Nyungar term that probably denoted a generalised category of edible insect larvae and have it identified by the prominent British taxonomist to a single Linnaean species. This has only confounded researchers to this day as to the true ethnographic and indigenous meaning of bardi.

We find it ironic that Grey was the one who restricted it to a single species yet it was through the popularity of his work and its accessibility to his colonial colleagues that the term bardi became part of the lingua franca of a number of Aboriginal languages and was incorporated into the Australian-English vocabulary as a general reference to beetle and/or moth larvae.

Grub habitat descriptors – are these also bardi?

paaluck – Xanthorrhoea (grass tree) grub

The earliest name for the edible grubs found in decaying Xanthorrhoea or grass trees is paaluck recorded by Isaac Scott Nind, the resident medical surgeon at King George Sound between 1826-1828. Confusingly Nind records paaluck as the name of the grub and paaluc as the name of the grass tree in which it is found in abundance at a certain season.12 Collie (1832) similarly records the name of the grass tree grub as paluk. From that time onwards the term paaluc and its variants paluk or baluk (Grey 1840: 5, 112), ballak (Moore 1842), bullouock or barlock (A.Y. Hassell 1894) and palak (Douglas 1979: 84) have all been used to refer to the grass tree. 13

A more common name for grass tree is balga (Grey 1840, Moore 1842, Stokes 1846) or balgarr (Bunbury 1930). A plant or animal may have a number of names depending on which particular food, medicine or other useful product is being referred to, in which habitat, how it is best identified, extracted, prepared and consumed, and at what season or life cycle stage.

Our research shows that traditional Nyungar animal food resources sometimes shared the same name as the habitat vegetation in which they were found (e.g. paaluck and paaluc). This dual naming applied when culturally familiar visual and auditory signs indicated the presence of a particular animal food within a specific habitat or vegetation community

kurrang – Acacia (wattle tree) grub

Another example of a shared food habitat descriptor involving edible grubs is provided (albeit unknowingly) by Moore (1842: 63, 45) when he records kurrang as ‘the grub of the Menna; Acacia greyana’ [that is, Acacia acuminata, jam wattle] and gurang as ‘the excrement of the wattle-tree Bardi, or grub; which oozes from under the bark of the appearance and consistence of clear gum.’ These two terms kurrang and gurang are one and the same and communicate certain visual and auditory cues to the presence of edible grubs in wattle. The Western Mail newspaper refers to cooranga (a regional variant of the term kurrang) as:

‘a grub or “bardie,” which was regarded as a delicacy by the blacks. As a result it might be applied to an area where good food was plentiful.’

We would suggest that if cooranga was a place name indicating plenty of edible grubs, it would probably have been rendered as coorangap or coorangup because ap or up affixed to the end of a word means ‘place of.’ Ethno-historical accounts would seem to suggest that paaluck and kurrang are both perceptible indicators of the presence of larvae in the decaying grass tree (paaluck) and the diseased wattle (kurrang).

Curiously, Grey (1840, 1841) does not provide a Nyungar name for the wattle tree grub, which Moore (1842) refers to as ‘the wattle-tree Bardi’ or kurrang. However, Grey describes the “excrescences” which indicate its presence:

‘When there is a grub in a wattle-tree, its diseased state, which produces excrescences, soon betrays this circumstance to the watchful eyes of a native, and an animal much larger than those found in the grass-tree is soon extracted; they seldom however find more than one or two of these in the same tree.’ (Grey 1841: 289)

Another article in the Western Mail (1935) refers to a large white grub found in the stump of an old collapsed Acacia tree in the Perth suburb of Bassendean. The specimen that was sent to the Government entomologist for identification purposes was identified as ‘the larvae of the large bardi moth (Pielus hyalinatus)’ and it was stated that Aboriginal people ‘are very fond of these grubs as food.’ These native wood-boring larvae attack wattles and sometimes Eucalpyts. The article describes how the condition of the wattle tree indicates whether larvae are present:

‘As a rule, wattles are not seriously damaged by the grub until well past their prime of life. When attacked the tree shows symptoms by the affected branch dying. Examination of the branch will disclose the hole where the grub has entered, with its excrement around the outside of the tunnel mouth’ (Western Mail 1935).

A.Y. Hassell lists bejenup as the name of the red bardie found in the jam wattle (Bindon and Chadwick 1992: 210). This sounds like a localized place name referring to the place where red bardie are found (up in the Nyungar language denoting ‘place of’). 14

What’s in a name?

The Nyungar people had no difficulty in giving descriptive tags to their relished larval fare. Alfred Bussell (n.d.) who was observing Nyungar culture in the 1830’s records seven names for grubs eaten by Nyungar people. These are boodjark, bunark, mundark, marnung, mairl, mutarnuck and palger. Some of these we have been able to translate, for example, boodjark referring to grubs found in the boodjar (ground) and bunark denoting a woodborer or woody tasting grub (buna, boona, boon meaning wood). 15

Bussell’s (n.d.) term mundark is the same as Grey’s (1840: 80) marn-duk referring to ‘a species of grub eaten by the natives.’ This is probably a derivative of mandakin meaning ‘young’ referring to the immature life cycle stage when these larvae were consumed. It is also not out of the question that the term marnung recorded by Bussell (n.d.) may be a linguistic derivative of marrine or marino meaning food or even marinuck, hunger.

Bishop Salvado (1851) records iular as the Nyungar term for an edible worm. This simply translates to yoolar or bark, indicating where to find the grub. There are many possibilities as to which grub he is referring as most wood boring larvae begin their life cycle under the bark of their habitat tree. In indigenous taxonomy edible woodborers sometimes take the name from, or give it to, their host habitat. A good example of this is wandona (Grey 1840) or wandunu (Moore 1842) referring to the edible larvae (possibly Phoracantha sp.) found under the thin bark of diseased or drought-affected wando (or wandoo). 16 We have observed longhorn beetles in their larval and adult states under the bark of water-stressed Eucalyptus wandoo and Acacia on our property at Toodyay.

In the 1970’s the linguist Von Brandenstein (1979: 47) believed that he was recording the Nyungar name for a local species of wattle known as Acacia glaucoptera found in the Esperance region. He records the plant’s name as “paarde-paatt” but he writes “perhaps not a name but a quality term?” He was right in a sense but did not understand the food resource value of this particular wattle. What his informants were obviously referring to was that it was an important habitat for fat-rich barde or what he calls “paarde –paatt.”17

Moore (1834) in his journal describes a similar type of grub found under the bark of the red gum. He states:

‘The natives have been feasting on a sort of grub or worm which they find in numbers under the bark of the red gum trees. Those that I have had cut down present a fine store for them to have easy access to. The grub is a sort of long four-sided white worm or maggot, with a thick flat square head and a small pair of strong brown forceps set on the end of the head’ (Moore 1834 in Cameron 2007:317).

It is surprising to us that Moore (1834, 1839) did not enquire as to the Nyungar name for this larva, especially as it provided a feast for Aboriginal people visiting his property in late March 1834. From his description we suspect that the larva was probably ‘the marri borer’ (a Phoracantha sp.) found under the bark and wood of marri (and various other Eucalpyts). Like the wandona, they range in size from 30-50 mm and are found in the cambium layers between the bark and sapwood. Phoracantha is a relative of Bardistus belonging to the same longhorn beetle family Cerambycidae. The red gum larvae were probably members of the bardi tribe.

Wool-gang – Is this a moth larva?

One Nyungar term the meaning of which has long baffled us is wool-gang. Grey (1840: 129) records wool-gang as ‘a species of barde.’ If barde is viewed as a general term for edible grub, then maybe Grey is right in that wool-gang is a type of barde. Moore (1842: 78) defines wulgang as:

‘A grub found in the Xanthorrhoea or grass tree, distinguished from the bardi by being much larger, and found only one or two in a tree, whereas the bardi are found by hundreds.’

He suggests that edible grubs were distinguished by size – the bardi referring to the smaller, more numerous and gregarious larvae-feeders found in grass trees and wool-gang being a larger more solitary larva. Could it be this simple? This theory seemed logical to us at the time. However, after finding a reference by A.Y. Hassell (1894) to wourl as meaning moth, we realized that Moore’s informant was probably describing the large edible larva of a moth. The gang in the compound term wool-gang may even be a linguistic rendition of nganna or nganning meaning ‘to eat’ or ‘to swallow’ indicating how to consume the grub. What we tend to forget today is that every Nyungar person at that time would have had an expert knowledge of the different life cycle stages of their favourite foods.18

Moore (1842:5) in his Descriptive Vocabulary points out the difference in size between bardi or edible grubs found in Xanthorrhoea (grass tree) and those in Acacia (wattle):

‘The Bardi of the Xanthorea are small, and found together in great numbers; those of the Wattle are cream-coloured, as long and thick as a man’s finger, and are found singly.’

Are these large cream-coloured grubs of the wattle, also called wulgang? Grey considers wool-gang a type of barde but does not elaborate. Wood moth larvae found in the roots and stems of Acacia typically pupate underground and work their way up through tunnels to the surface where their reddish-brown chrysalis shells can be seen protruding from tree trunks or holes in the ground from where the adult moths emerge.19 When we asked a group of Nyungar Elders from the Perth region about the term wool-gang, they said that they had no knowledge of this name and that they called all edible grubs bardi or witchety grubs.

Fieldwork with Nyungar Elders

When Nyungar Elders were asked about the collection of (what they called) bardi one senior spokeswoman told us that when it was bardi– collecting time there were indicators in the surrounding vegetation and roots of nearby trees. She referred to them as “boodjar bardies” – the ones that live in the ground (boodjar). These, she said, had to be dug out from the roots of wattle using wannas (digging sticks). It was hard work and very time-consuming. She added:

‘They knew where to look for these bardies. You could see their holes in the trunks of trees and some sawdust around it…and holes in the ground.’

By ‘sawdust’ she was referring to what is known as frass – ‘the fine powdery refuse or fragile perforated wood produced by the activity of boring insects.’ This term also refers to ‘the excrement of insect larva.’ 20

All of these physical manifestations would have been easily discernible to the sharp-eyed bardi-hunter. Roth (1901) writes, referring to Austin’s first hand experience in south-western Australia, that the Nyungar people of the Bunbury/ Australind area ate grubs from the grasstree and black wattle and knew where to find them by the degree of decay in the wood.

During one of our field surveys in the Moora area (north of Perth) in the 1990’s a Nyungar woman announced to us that her grandmother told her that the ‘old people’ could hear the bardi “sing” in the wattle when it was ready for eating. At the time we had no idea what she was talking about and thought it may have been some obscure mythological reference. But now we are wondering, in hindsight, could it be that her grandmother was referring to women listening for the noise made by grubs as they chewed through fibrous wood. This is a possibility, for African women located edible beetle larvae by holding their ears close to tree trunks and using subtle auditory indicators, such as the “nibbling” sounds of the grubs, were able to locate “the most sought-after instar (the developmental stage of an insect or larvae).” (Van Huis et al 2013:11).

An obscure early reference by Moore (1841: 311-312) to the Nyungar people of the Swan River area notes that ‘When the bark of a living tree in which they [grubs] are found is struck, they make a sound like the ticking of watches.’ Hercock (2009: 73) also refers to the auditory location of bardi grubs by Aboriginal people in the Little Sandy Desert north of Wiluna where the grubs, known as bardi or lungki, can be heard munching and crunching the wood of old decaying wattle trees, if one listens carefully.

Birds are also known to locate wood boring grubs by means of their sounds. Seaton (2012: 23) notes that ‘Birds are likely to locate Cerambycid larvae in trees by listening to their sound whilst feeding (Linsley 1959).’ We would suggest that certain birds, such as magpies, cockatoos and tree creepers may have also indicated the presence of bardi.

A male Nyungar Elder from the Perth area described to us how ‘the old people’ used to collect bardi from the wattle tree. He said that they would search for a suitable tree, usually one that was dying or showed signs of sawdust near its base and they would flick the tree with their fingers or tap it with a piece of wood and if it sounded hollow, they would strip off the bark and break the branch to see on which side of the branch the bardi was located. If deep inside its burrow, they would use a thin, springy hooked twig to pull it out. This hooked twig was made from whatever flexible material was available. It was inserted into the bardi burrow keeping it carefully to the side until it reached the top of the bardi’s head at which point the twig was twisted and the hook opened. The bardi was then carefully extracted.

Drummond (1843) writing in the mid-19th century describes how Nyungar people made a hook using the flexible thin branch of Melaleuca radula or tea-tree ‘to extract an edible grub which they find in the manna gum [Acacia].’ The name of the hooked stick he records as numbat, although we suggest that this may have been a typographical error (of which there are many) in the typescript or, alternatively, his Scottish way of rendering the Nyungar term nambar meaning ‘a barb.’

Bardi collecting in this manner was still occurring in the 1930’s in the Kendenup area as reported in the Western Mail:

‘I have not seen the natives securing bardies from roots but have watched them getting them from the limbs of bushes and trees. They can pick a bardie limb yards off the general line of march. How, I don’t know. Getting the grub is a work of art sometimes. If the branch does not break where it is, the hunter selects a thin twig with a small knot on the end, runs it down the hole and hooks him out.’ (Western Mail 15th August 1935: 8)

To complicate things further Whitehurst, a Nyungar linguist, records the meaning of kurrang as ‘to twist and turn.’ This may be interpreted as the skilful movement that is required to extract the bardi from its burrow. This adds another level of meaning to the term kurrang that refers to the edible grub found in wattle and ecological indicators of its presence, such as excrescences or frass (residue) and how it is extracted from its hole or tunnel under the ground or in the tree trunk.

Bardi collecting was a seasonally based activity carried out by men and women, although women and children were mostly responsible for the labour intensive task of digging out the grubs from the roots of trees using their wannas. Men would often consume grubs opportunistically while out hunting for larger game, such as possum or kangaroo, as noted by Grey (1841) and Hammond (1933:40-41) who states:

‘As he walked along, with his eyes alert, the native could tell, too, which trees had opossums in them and which trees or blackboys would have grubs. According to the chance of the day he might turn aside to get an opossum from a tree, or to get some handfuls of bardie grubs, which might be eaten raw as a snack by the wayside.’

Taste of the bardi

Grey (1840:7) describes the barde from the Xanthorrhoea as having ‘a fragrant aromatic flavour’ and tasting ‘very like a nice nut’ (1841:288). Grey was the first to convey the aromatic nutty flavor of the barde and from that time on the taste of barde was compared to a nut. Moore (1841) describes it as a chestnut flavour. Bishop Salvado writing in 1851 (in Storman 1977:207-208, 263) describes the grubs (pari) that were consumed by Nyungar people in the New Norcia area as tasting like roasted chestnuts when cooked:

‘Certain yellow worms which the settlers called ‘grubs’ and the natives call ‘bardies,’ found in the grass-tree or blackboy, when this has gone rotten. These grubs are as thick as a boy’s little finger, and they form a favourite and common food of the natives, who eat them either raw or roasted. The first way, they have a taste that reminds one of the resinous smell of the trees from which they come; the second way they taste like roasted chestnuts…. Other worms which differ only in size, being larger in this case than a man’s index finger, are found in the roots of certain wattles, and in the trunks of some eucalypts. They serve the natives as food in the same way.’

Bradshaw (1857: 99), referring to the Nyungar people of the Swan River area, notes that:

‘there are also three kinds of grubs that the natives are fond of and which sometimes they cook, but oftener eat raw. When cooked they have the taste of sweet chestnuts and are very good.’

These early colonial descriptions are culturally relative and reflect the writer’s familiar European taste sensation in the context of their country of origin (e.g. roasted chestnuts). More modern descriptions describe bardi as having a fatty, peanut butter-like taste, or a creamy nutty taste as noted by Ethel Hassell writing in the late 19th century. She writes:

‘Bardie – a large white grub found in the roots and under the bark of certain trees. It is greatly prized as a food and is eaten either raw or roasted. The taste is said to be similar to that of pounded almonds with cream.’ (Hassell 1935: 276)

We find it surprising that Hassell did not herself sample the bardie. She was known to experiment with Nyungar foods, including the spicy hot meen (Haemodorum, red root) that assaulted the mouths of her menfolk, much to their displeasure, when she added it to a beef stew!

Cowan (1865) refers to the consumption of marrow-like grubs but it is unclear whether he is referring to their fat-rich taste or something else. He states:

‘The trunk of the grass tree . . . (Xanthorea arborea), when beginning to decay, furnishes large quantities of marrow-like grubs which are considered a delicacy by the aborigines of Western Australia.’ (Cowan 1865:70-71).

Chauncey (1879: 248) describes ‘the larvae of a species of cerambyx called bardi’ having

‘a delicate aromatic flavour, and affords him a delicious treat. They are about an inch long, and sometimes fifty or a hundred are found boring their way through one grass-tree.’

Calvert (1894:28-29) also comments that:

‘Grubs, which are extremely palatable, are procured from the grass tree; and likewise in an excrescence of the wattle tree. They are eaten either raw or roasted but seem to be greatly improved by cooking. I am told they have a nut-like flavour, but I never had the courage to sample them.’

Bates (in White 1985: 260) compares the taste of wattle tree and grass tree grubs:

‘The wattle tree grub is the largest, and the most delicately flavoured. Not more than two of these are found in a wattle tree, unlike the Xanthorrhoea grub of which over a hundred can be found in a good tree. The blackboy (Xanthorrhoea) grubs have a flavour very like a good hazelnut.’

Hammond (1933) provides practical instructions on how to eat a bardie and indicates which ones taste best:

‘The “bardie” grub – a fat white grub found in blackboys or wattle trees – was either eaten raw or cooked. For cooking grubs, the natives would brush the burning coals aside and place the food on the hot ashes. The grub would be taken up in the fingers off the coals, the fleshy part nipped off with the teeth and the head thrown away. If eaten when they were young, these grubs tasted like the marrow from unsalted beef bones; but the older ones tasted woody, having too much sawdust in them. The grubs from the blackboy and wattle were the best. Those from banksia trees were always woody.’ (Hammond 1933:30)

The tastes associated with the consumption of bardi seem to emphasize its nut-like flavour. Early recorders likened it to ‘a nice nut’, ‘roasted chestnut’, ‘sweet chestnut,’ ‘a good hazelnut’ or ‘pounded almonds with cream.’ Did these early writers actually taste the bardi or like so many of their descriptions, did they copy from others, especially given their culturally ingrained revulsion towards grub eating. It is highly probable that Hammond is relating his own personal bardie tasting experience for he describes their fatty, marrow-like taste and even distinguishes the flavour of young and old larvae. Having lived for many years with semi-traditional Nyungar people, he would have understood the coveted taste of fat in their diet. It is difficult for us to comprehend the importance of fat to the survival of traditional hunter-gatherers living in the temperate regions of Australia because in our modern day society dietary fat has been the subject of controversy and often attributed to negative health consequences.

Nyungar people ate the larvae of a range of beetles and moths, including that of the rain moth (Trictena atripalpis). Tindale (1938) describes the taste of the lightly roasted larvae of the rain moth (also known as ghost moth) based on his experience in the Western Desert where these larvae are also consumed:

‘On one occasion when a grub was being dug out, it was injured in the process; the native cooked it by laying it in the hot ashes of his campfire for about half a minute. When the skin became taut with the warmed juices within it, he raked it out, flicked it with his fingers to remove the adhering dust and offered it to me. It tasted like warm cream or the baked skin on roast pork, and was quite delicious’ http://labs.russell.wisc.edu/insectsasfood/files/2012/09/Book_Chapter_27.pdf

Tindale (1953) provides a detailed ethnographic account of the procurement and consumption of mako witjuti (also spelt witchety or witchetty) – the grub or caterpillar of a large wood moth (genus Xyleutes now called Endoxyla) found in the roots of Acacia kempeana and consumed by the desert people of Central Australia Latz (1995: 103) identifies these large tasty grubs as Xyleutes biarpiti and points out that: “In exceptional seasons as many as fifty can be obtained from one bush, with an average of about three in each root.’ If they are injured during the extraction process they are usually eaten raw but otherwise are taken back to camp where they are lightly roasted in the coals. Latz (1995: 103) describes the flavour as ‘somewhat between that of egg yolk and almonds.’

Tindale (1953) points out that the term witjuti does not refer to the grub itself:

‘In the Arabana native language [South Australia] from which the term is taken, witjuti refers to the shrub, not to the grub, and must be prefixed by the word mako, meaning grub.

‘The chief foods sought by the women and children as they move across the country are edible wood grubs such as the mako witjuti from the roots of acacia (witjuti) shrubs. The mako living in tree-trunks are chopped out by the men.’ (Tindale & Lindsay 1963: 56).

Tindale (1953) emphasizes the nutritious qualities of mako witjuti as follows:

‘Aborigines with access to witjuti grubs usually are healthy and properly nourished…. Women and children spend much time digging for them and a healthy baby seems often to have one dangling from its mouth in much the same way that one of our children would be satisfied with a baby comforter’ (Oceania Ch. 28).

‘Often three or even four years would pass before the child was fully weaned but in the second year large witjuti grubs, with their rich store of buttery fat and tasty soft meat would be given to it’ (Tindale and Lindsay 1963: 109)

The drawings of Aboriginal people of Central Australia often involve circular or spiral designs known as kuri kuri often signifying the ‘home’ of a particular animal or plant. According to Tindale and Lindsay (1963: 81-82) if the drawer has ‘mako witjuti grubs in mind, the circular design may represent the roots of the species of Acacia tree in which that grub lives.’ Alternatively, if a circular or spiral design is associated with emu track representations, then these signify ‘a pool of water around which the emus live.’

It is not uncommon in the desert languages of Central Australia for the general word for edible grub to precede the name of the specific tree or bush in which it is found. Wallace and Wallace (1973:16) with reference to the Pitjantjatjara people of the Musgrave Ranges of South Australia observe this:

‘maku refers to edible grubs in general and the people themselves identify the different species according to the plant in which they are found.’

The same rule applies to the Arrernte (or Aranda) people of the Alice Springs area who put the general word for edible grub tyape before the name of the bush in which it is found. Henderson and Dobson (in Thieberger and McGregor 1994: 276, 282, 409, 547) provide the example of tyape atnyematye that refers to the ‘edible moth larva found in the roots of witchetty bushes.’ What we noted, when searching through the Arrernte word list in Thieberger and McGregor (1994) is that the term for witchetty bush atnyeme looks remarkably similar to the term for digging stick atneme (p. 409). Could this linguistic similarity suggest an associated meaning, similar to that which exists between witjuti (bush) and the wityu (hooked stick used to extract the grub)? Aboriginal terms often embody a number of associated meanings, depending on context. As noted witjuti may refer in popular usage to an edible grub but in linguistic terms to the name of the wattle bush in which it is found or the hooked stick used to extricate it, depending on context.

Australian linguists Dixon et al (2006: 103) point out that witjuti is believed to derive from the Adnyamathanha language of the Flinders Ranges, South Australia where wityu means ‘hooked stick used to extract grubs’ + varti, ‘grub,’ ‘insect.’ For this reason it is sometimes called the ‘hooked stick grub.’ Similarly the Nyungar term kurrang has a number of associated meanings, including the large edible grub found in Acacia (wattle), physical indicators of its presence and/or instructions on how to extract it – using a deft ‘twist and turn’ movement with a hooked stick.

The fat taste

Hunter gatherer people who lived in temperate zones where the winters were often long and severe, and food shortages common, evolved genetic adaptations to store a portable supply of energy in the form of subcutaneous adipose tissue. These fat reserves provided stored energy and an insulation barrier against the cold. These stores were replenished during times of plenty (Neel 1962). But what was the force that precipitated this drive to consume fat-rich foods?

The anthropology of taste has never been applied to the adaptive drive of traditional Nyungar people to consume large quantities of fat. In 2015 an American team of scientists isolated a sixth basic taste, what they called the “fat taste” or “oleogustus” (Latin, oleo, oily or fatty +gustus, taste) for selected fatty acids (Running et al 2015: 515). They note that the term “pinguis” has been used to describe fattiness since the 16th century (Fernel 1581) but they have coined a new term to refer specifically to the chemistry of taste rather than a textural connotation.

It is highly probable that hunter gatherer people who lived in temperate climates had a genetic predisposition that stimulated a fat taste signal that alerted them to consume in quantity high fat/ carbohydrate foods when available as a means of maintaining and storing body fat as an insurance against famine conditions. We would suggest that the taste sensation of fat in the diet stimulated an insatiate demand for energy dense foods. This may explain the many ethnohistorical references to Aboriginal people gorging on fat-rich foodstuff when available.

It is well documented that the Nyungar people had a voracious appetite for consuming all kinds of animal and vegetable fats and the fat-rich bardies were no exception. Fat was such an indispensable part of their diet that they had several terms to refer to it. These were djirang (Whitehurst 1992:35) which has also been rendered by recorders as chira, djeroong, jer-rung, jerring, jerrong, cheerung and jeerung. Other terms for fat include bwoine (also spelt boyn, bynyer, boyu, bwarn) and baring (Curr 1886). 21

Traditionally Nyungar people were well acquainted with plant and animal phenological breeding cycles which for the most part structured their seasonal calendar. We have no doubt that oleogustus would have been a well-developed sense in these traditional inhabitants and the fat taste would have been a driving force for them to consume as much of it as possible. Otherwise they would not have survived.

The Nyungar season known as jeran literally means ‘fat.’ It is an instructive seasonal descriptor signalling them to build up stores of subcutaneous body fat to ensure their survival through the lean, harsh, cold dark wet season of mokkar (Albany) or makuru (Perth) when food was less abundant and more difficult to procure.

According to George Fletcher Moore’s (1842) rigidly defined six-season Nyungar calendar this season of geran (as he spells it) pronounced djeran corresponds to April and May (late autumn). However, its duration would have varied, depending on localised weather patterns and the vagaries of autumn rainfall. It definitely would not have been restricted to such a neat arbitrarily defined two-month season. Nature does not work that way. Moore’s six-season model is oversimplified, Western-centric and ethnographically inaccurate. What he has done is to super-impose six indigenous named periods onto the Western-derived twelve-month Gregorian calendar. From a mathematical perspective six divides neatly into twelve, creating six seasons, each of two month’s duration. But this theoretical model is flawed. The traditional Nyungar hunter-gatherer-cultivator calendar was based on solar and lunar cycles interlinked with plant, fish, bird and animal phenological breeding cycles (seasons) and sub-cycles (sub-seasons) – not a white man’s adapted version of the Gregorian calendar (see Macintyre and Dobson, Notes on the Nyungar seasons, forthcoming).

Time of the bardi

Bardi being a general term for edible grubs makes it impossible to define a specific ‘bardi-grub season.’ Grubs would have been consumed at different times of the year depending on their larval cycles and climatic conditions. Some ethno-historical accounts provide fleeting references to the opportunistic consumption of grubs to appease hunger, and sometimes, as noted by Collet Barker (1830) as a survival food found in the grass tree. Collet Barker notes in his diary on 6th February 1830 when exploring the southern coastal region in the vicinity of Denmark that he: ‘Tasted on the way some grass-tree maggots found by Talpan, very sweet & good.’ He also writes on 12th March 1830 with reference to a group of young Aboriginal men:

‘Since I saw them, they had been constantly walking, not stopping even to spear Wallabi, Kangaroo, etc, & always hungry & tired, merely, it would seem, supporting life by a few roots & the grass tree maggots’ (in Mulvaney and Green 1992: 260, 273).

Grey (1841: 93) documents an anecdote that gives us a further clue as to when barde were in season. Were these the barde identified by Newman as Bardistus cibarius? Grey informs us that on 20th April 1837 when returning to Perth in an undernourished condition, he was fed generously by his Aboriginal guide Imbat, who, taking pity on him, had said:

“You are thin,” said he, “your shanks are long, your belly is small … “I know how to keep myself fat; the young women look at me and say, Imbat is very handsome, he is fat – they will look at you and say, He not good – long legs – what do you know? where is your fat? what for do you know so much, if you can’t keep fat? …‘and I know how to make you fat,” – began stuffing me with frogs, barde, and by-yu nuts.’

Imbat was imparting his cultural wisdom by telling Grey that without fat on his body, he would not be considered “handsome” and would not survive the coming winter, let alone his journey back to Perth. This was not an idle comment but was based on a tried and tested cultural imperative. Grey was being fed barde during the season known as djeran the duration of which varied but was approximately from late March to late May/ early June, depending on weather patterns and flora, fauna and avifauna life cycles. Nyungar people traditionally hunted and harvested animals and plants when they were at their fattest. For example, emus were primarily hunted in winter (known as mokkar at Albany or makuru, Perth) during their breeding season when they had accumulated significant body fat reserves to sustain themselves through the breeding season, in particular the two month incubation period when the male stays on the nest. Salmon were caught at Albany during meerteluc at the time of their spawning (approximately February to April). Birds’ eggs and young nestlings were hunted during maungerman and mondyianong (spring) when they were full of nutritious fats. Communal kangaroo drives and battues were conducted in late spring at a time when the young were being de-pouched from their mothers. The young of most species were nutritionally favoured and beetle and moth larvae were no exception. Larvae such as the cockchafer were active during djeran (mid-late autumn) and they contained essential fats that were critically needed by the Nyungar hunter-gatherers to build up condition.

It makes sense that the Nyungar had a season named djeran (from jeerang or djirang meaning fat). This fits with other hunter-gatherer people living in temperate zones whose bodies were bio-chemically adapted to increasing their body mass and energy stores in the form of subcutaneous fat in response to the seasonal reduction in light intensity and day length (known as photoperiod). The Nyungar not only evolved the ability to store body fat but the timing of this storage was critical, albeit subject to the vagaries of weather and animal breeding cycles. During these cyclic events there was intense competition between birds, humans and animals for the limited food resources – all preparing for the long cold dark wet season.

Fat is the currency of hunter-gatherer survival in cool temperate zones where climatic conditions are less predictable. To survive the Nyungar people must have devised means of provisioning themselves with essential fats; otherwise they would have died out. When we remember back into the long distant past when we were anthropology students, we were told that Australian Aboriginal hunter-gatherers depended solely on the seasonal availability of foods and that surplus and storage were not considered part of their subsistence economy. This may have been the view of the early European recorders who viewed agriculture from a strictly Western-centric perspective but as the ethnographic evidence shows, the Nyungar practiced a type of mini-livestock farming.

Larvae farming

The classic notion of hunter-gatherers as nomadic, opportunistic foragers relying solely on the vagaries of nature to sustain themselves is misleading. The Nyungar like all other Australian Aboriginal groups had a great knowledge of plant and animal phenological breeding cycles to the point where seasonally reliable resources were managed or “farmed” to mitigate against catastrophic food stress. It was not farming in the conventional sense of the word but a form of habitat modification and management that was carried out over a prolonged period.

It was the Native Interpreter, Mr Francis Armstrong (1836) who first made reference to the Nyungar people in the Swan River area seasonally modifying part of the natural environment to produce a reliable supply of edible grubs. He refers to the traditional inhabitants ‘taking the trouble to break down the grass-tree, by which the production of their favorite grub is much hastened’ (Armstrong 1836:10).

Almost ten years earlier Nind (1826-1828) while resident medical officer at King George Sound (Albany) observed this same practice among the Minang (Nyungar). He writes:

‘At one season of the year, the natives push or break down the grass-trees, on which, when fallen, a species of cockchafer (paaluck) deposits its ova, which become large milk-white grubs, and these they eat raw, or slightly roasted. There are also other kinds (changut), some of much larger size, that are procured from rotten trees, bull-rushes, &c.: all of them are white.

Of their paalucks they are extremely tenacious; the person who breaks down the tree being entitled to its produce. And if robberies of this nature are detected, the thief is always punished. They believe also that stolen paalucks occasion sickness and eruptions. Yet, when hungry a friend will not scruple to have recourse to the grass-tree of another who is not present; but in this case he peels a small branch or twig, and sticks it in the ground, near the tree. This is called keit a borringerra, and is intended to prevent anger or other ill consequences.’ (Nind 1831:34)

Nind’s (1831) account implies that Nyungar people practiced a form of insect husbandry to increase the natural production of this seasonal food resource. He records paaluck as ‘a species of cockchafer’ found in abundance in decaying Xanthorrhoea (grass tree). He also refers to some larger sized grubs found in rotten trees and bulrushes as changut. This may be a reference to white grubs for changer (or janga) may translate to ‘white.’ 22

The names for the edible grubs found in Xanthorrhoea are recorded by Nind (1831) as paaluck, by Collie (1832) as paluk and by Grey (1840), who is also referring to the King George Sound region, as barde.23 Nind (1831) describes it as a cockchafer (scarab) larva whereas Grey (1841) identifies it as a cerambycid (longhorn) larva. We have no doubt that the Nyungar would have consumed the larvae of cockchafers, cerambycids and buprestids, so long as they were edible. We are convinced that paluk and barde are descriptor names and do NOT – as tempting as it may be – translate to Linnaean species or family names.

Grey’s (1841:289) comments, together with those of Nind (1831), confirm that by breaking off the tops of selected Xanthorrhoea the Nyungar were able to accelerate the decay of the plant and create a raising medium for the cultivation of wild insect larvae. This was a form of natural and sustainable resource management that could be viewed as an early form of insect husbandry or farming. Grey (1841) writes:

‘Until the top of the tree is dead, it is not a proper receptacle for these animals, the natives are therefore in the habit of breaking off the tops of the grass-trees on their land at a particular season of the year, in order that they may have an abundance of this highly prized article of food. If two or more men have a right to hunt over the same portion of ground, and one of them breaks off the tops of certain trees, by their laws the grubs in these are his property, and no one else has a right to touch the tree. No mistake on this point can occur, for if the top of the tree dies naturally it still remains in its original position, whereas a native who thus prepares the tree knocks it off altogether….’ (Grey 1841: 289)

Bates (in White 1985: 260), who seems to have copied from Grey’s work, writes:

‘If the top of the blackboy looks somewhat withered it contains some grubs, and with a few kicks the tree falls over, the grubs being found at its root (sic.) Until the tops of the grass trees are dead, the grubs are not matured and to hasten this end, a native will break off the tops of the grass trees at a particular season. If two or more men belonging to the same hunting ground, break off the tops of certain trees, these trees are the individual property of the person who broke their tops off, until the grubs have been extracted, no one else having a right to touch the grubs, except the young children or grandchildren of the owner of the trees.’

The farming method

From the meagre information available it is impossible to ascertain the extent of an individual or group’s paaluck nursery. This would have been dependent on the natural abundance of Xanthorrhoea within a particular district. We suspect that the Will territory visited by Collie and his Aboriginal guide Manyat in 1832 may have produced quantities of nutritious paaluck as Collie writes:

‘The grass trees common to Western Australia became frequent, and Manyat inferred (from their abundance, I Suppose) that we had now reached that part of the Country where “black fellow ta paluk” (live upon the grubs which form on the decaying grass trees,) for by the word ta he [Manyat] here evidently meant that the natives gained a chief part of their Subsistence by this food, which he confirmed by comparing the King Georges Sound tribe eating Meen (the red root) to the tribe (Will?) of this part eating the grubs in question.’ (Collie May 1832 in Shoobert 2005: 311).

In drawing a comparison between the paluk eaters (Will) and meen eaters (Minang), Manyat seems to be implying that the protein-fat rich paluk gave the Will a survival advantage over the Minang who by this time of the year may have been consuming the less nutritive vegetable foods such as the red root of Haemodorum spicatum known by them as meen or meernes.24

The method of paluk (or barde) farming involved a traditional scientific knowledge (TSK) of plant and insect phenology that had developed over many thousands of years of empirical observation and practical experience. By deliberately destroying the apical growth of living grass trees, the Nyungar were able to secure a reliable food supply that was customised to their needs. This would have involved a high energy input by the male owners of the Xanthorrhoea patch, to destroy the plant to hasten its decay, thereby providing a suitable medium on which the adult female beetle deposits its eggs.

This type of farming would have involved long term planning and selective management of Xanthorrhoea resources. Paluk production was a smart means of live storage of a reliable food source highly esteemed for its protein and fat-rich content. As the larvae matured an astute sense of timing and human surveillance would have been necessary to protect this highly coveted resource from competing predators, such as native animals (e.g. kwenda, bandicoot and dalgyte) and birds such as the cockatoos that also like to feast on bardi. It is understandable that they would have resorted to sorcery and violence as a traditional means of dealing with trespassers and theft of such a valued food resource. The theft of other highly coveted fat-rich food resources, such as the by-yu (processed Macrozamia seed coat) also incurred the risk of death. 25

We imagine that a spiritual component may have been involved in paluk husbandry in order to ensure a plentiful harvest. Ritual increase ceremonies were carried out for other valued animal and plant foods to maintain and enhance their yields, usually at designated totemic sites known as ‘increase sites.’ Bates (in White 1985: 201) refers to ‘the bardee (grub) totem people’ at Berkshire Valley (to the east of Moora). Bardee totemic knowledge and rituals were not confined to a single district but were inter-connected with bardee (grub) totem people in other parts of indigenous southwestern Australia from where the term originated.

We speculate that the indigenous practice of insect larvae farming as practiced by the Nyungar would have evolved over many thousands of years of empirical observation whereby the natural life cycle processes of beetles and moths were observed and their larvae randomly procured from dead and decaying Xanthorrhoea. By means of intervention they were able to hasten the natural cycle of insect production and increase resource productivity. The anthropogenic firing of the country played an important part in the long-term management of this food resource by stimulating seed germination and regenerating new growth as a future medium for larvae-farming purposes.

Where do we go from here?

It is difficult to gauge the extent to which Nyungar people relied on the consumption of insect larvae as a source of dietary nutrient. From the wide assortment of Nyungar names recorded for unspecies-fied edible grubs, it would seem that this component of the diet provided essential energy, fat and protein. Our analysis of ethno-historical sources revealed over 15 different terms for edible grubs, the most common of which is bardi (also rendered as bader, bada, barde, bardi, bardee, burrt, bert, berda, barit, pari, paarde-paatt). Other terms for edible grubs (some of which we have attempted to translate) are bejenup, boodjark, boo-yit, changut, bunark, iular, kurrang, marnduk, marign, marnung, mairl, mutarnuck, nargagli, paaluck, palger, wandona and woolgang.

It is our opinion that these grub descriptors were used by Nyungar people in an attempt to describe to foreigners in a form of meta-language how and where to find edible grubs, their nutrient value and how to extract them from their hollows. They were providing useful information on how to survive in their country but the foreign observers generally misinterpreted these emic ‘descriptors’ as being individual species names. Assigning Nyungar names of undetermined insect larvae (and pupae) to Linnaean species is a daunting if not impossible task owing to the fact that Linnaean classification relies exclusively on adult insect specimens whereas traditional Nyungar taxonomy and nomenclature focus on the edible fat rich larvae.

The difficulties associated with identifying larval forms before their metamorphosis into adult insects was highlighted in old newspaper accounts where readers were told by WA Museum experts not to send in the grub for identification but to let it mature and then send in the adult specimen. To this day, little has changed.

In traditional taxonomy, as we have noted, grubs were not differentiated according to a Linnaean speciation model but were classified by means of emic “descriptors” based on practical criteria such as edibility, size, colour, habitat, lifecycle stage, nutritive fat content and seasonal availability. A grub may have a number of descriptor names or associational names that describe the habitat or host plant in which it is found, how it is procured, indicators of its presence (such as excrescences, saw-dust like residue around base of tree) and the type of hooked stick used to extract it. These various descriptor names would suggest that knowing how to find the food and how to extract it was more important than its actual name. Maybe it didn’t need a name, at least not an arbitrary or independent designation (as we know them). The sharp eyes of the hunter were culturally attuned to detecting ecological tell tale signposts around them suggestive of insect activity. They knew what they were going to find inside decayed grass trees and wattles at certain seasons of the year. Have we ever been that hungry where the name doesn’t matter so long as the food is edible?

To a Westerner, bardi usually means a grub or worm bait used for recreational fishing. However, Nyungar people prized the bardi for its nutritional fat content. We would even suggest that it may have been a descriptor alluding to the life-sustaining fat and energy qualities of this food. Earlier in our paper we suggested that nargagli – a descriptor name for edible grubs found in the grass tree – may translate as meaning ‘strong, powerful to eat.’ Using the same cultural logic we would speculate that the edible grubs referred to as barit, pari, burrtt, bert (and their variant renditions) may derive from the Nyungar term baring which according to Curr (1886) means “fat.”

Recapping the puzzle

Grey’s (1841) attempt in the name of Western science to have barde identified to species has only confused the issue. It has led to some researchers attributing bardi to the larva of the cockchafer beetle and others to the larva of the buprestid (jewel) beetle (Yen 2010: 76) and others who agree with Grey (1841) that it is the larva of the cerambycid longhorn beetle Bardistus cibarius. What we have here are three separate families of beetle. Furthermore bardi sometimes also describes the edible larvae of certain moths (such as the rain moth Trictena atripalpis). So what is this bardi?

The word bardi originates from the Nyungar language where it first appeared in print in 1836 in Bunbury’s journal as bader (‘grass tree grubs’). The views of contemporary Nyungar Elders and those of historical accounts suggest that bardi is a general term for edible wood-boring grubs found in a range of habitats, with Xanthorrhoea (grass tree) and Acacia (wattle) being the most commonly described examples. Throughout our conversations with the Elders it was never specified whether these were the larvae of beetles or moths. Both were favoured for their nutritive fat content and were loosely referred to as bardi or witjuti grubs. 26

Traditionally animals and birds were hunted and consumed in the season when they were at their fattest. This included the young of most species that were highly favoured in the diet. Fat consumption was a cultural imperative for hunter-gatherer survival. The logic to eating fatty foods was to conserve and build up energy reserves. Eating lean meat without the accompaniment of fat or carbohydrate had negative effects – it expended valuable body fat and energy in the digestion of protein. The consumption of fat was essential during the period known as djeran (approximately late March to late May). This was the time for maximizing subcutaneous body fat to ensure survival through the long cold wet season when food resources were limited and less easily procured due to the adverse weather conditions.

In this paper we have suggested that bardi is a collective term for edible grubs, referring to beetle and moth larvae. However, this is not to say that Nyungar people did not make finer distinctions based on taste and fat content, larval size, colour, habitat, life cycle stage (newly formed larva, mature larva, pupa) and seasonality. Sometimes shared habitat descriptors are used, such as paaluck (Xanthorrhoea), kurrang (menna wattle, Acacia), wandona (wandoo) and boodjark (underground bardies) indicating where to find the grubs or physical and ecological indicators, such as excrescences or observable frass. It is sad that such a wealth of traditional ecological and scientific phenological knowledge, including the habitat and life cycles of edible native insects, has been lost to the world since European settlement. 27

We have no doubt that traditional Nyungar hunter-gatherers after tens of thousands of years of empirical observation and acquired knowledge would have known in the finest detail the reproductive biology of their important insect foods. We would suggest that insect farming evolved from this valuable traditional knowledge.