Roots of contention: Noongar root foods and indigenous plant taxonomy

Roots of Contention - Noongar Root Foods and Indigenous Plant Taxonomy

Identifying root foods to individual Linnaean species is always problematic because the Noongar had their own criteria and means of classifying plant foods which did not match the Linnaean speciation model

(Macintyre and Dobson 2017).

The Noongar people of southwestern Australia, like other Aboriginal groups throughout Australia, over many thousands of years accumulated a vast database of empirical knowledge founded on direct observations and experiences of the world around them. This knowledge was handed down through successive generations by oral narrative and song. It included scientific knowledge (ecology, biology, zoology, climatology, astronomy and phenology etc) understood from an indigenous perspective that was often encoded as metaphor in traditional narratives. Indigenous survival would not have been possible without this practical knowledge.

In our other papers we have questioned the relevance of the 18th century European-derived Linnaean botanical speciation model with its focus on above-ground plant features, especially the minutiae of leaf, flower, seed and stem anatomy to hungry hunter-gatherer-fisher-cultivators whose botanical classificatory system was survival-based. Minor morphological variations in leaf or stem structures were of little importance compared to a plant food’s edibility or usefulness as a medicine, ornament, shelter, artefact manufacture or other activity.

Noongar people evolved their own logical, independent, highly practical and utilitarian-based plant, animal, fish and bird classificatory systems based on practical criteria many thousands of years before Europeans settled in Australia and long before the Linnaean system was introduced into Europe. So why do contemporary researchers, especially ecologists, archaeologists, ethnobotanists and anthropologists, continue to perpetuate the myth, originated by the early colonial recorders, that Noongar botany can be viewed through the prism of our familiar Western-derived Linnaean speciation system? This is Western-centric, misleading and distorts past ethnographic reality. It wrongly assumes that Aboriginal people had their own Linnaean speciation system that somehow paralleled the Western model.

So how can we understand indigenous botany without using our own familiar Linnaean model of species differentiation? This is very difficult as we are Western-trained and the Linnaean model provides the only familiar tool that we have for analysing plant taxonomy. Also, it has been imposed on indigenous taxonomies of plants, animals and birds ever since the colonial records began in Australia, so how can one undo this? What we should recognise, however, is that the Western derived Linnaean speciation model was largely unimportant in indigenous classification and that Noongar names for plants, birds, fish and animals were generally descriptors that applied collectively, frequently across Linnaean species and even genera categories, depending on indigenous perceived similarities of structure, function, identification, consumption, season of harvest, taste, nutritional qualities, life cycle stages, totemic significance or other considerations. These indigenous identifiers often included habitat descriptors, ecological descriptors, human body part metaphor descriptors and others.

Indigenous descriptors

Aboriginal names for plants or “descriptors” describe distinguishing aspects of plants based on practical and utilitarian criteria which from an indigenous perspective enabled food resources to be easily identified and located. These descriptors were instructional in that they advised whether certain roots, tubers, gum, nectar, seeds, leaves and fruit were edible or useful as medicine, decoration, artefact manufacture or whether they were “fodder plants” for birds and animals which in turn became a source of human dietary protein and fat. Plant descriptors often conveyed information on aspects of food such as taste, nutritive value, root or fruit shape, stage of life cycle when harvested or indicated totemic or mythological significance.

This paper describes and illustrates some common Noongar root foods which formed an important part of the traditional Noongar diet. Owing to the fact that Western botany and its speciation model focuses largely on the above-ground features of plants – rather than their below ground storage organs which were of paramount importance to hunter/gatherer/cultivator Aboriginal people as food – it has been difficult for us to locate photographs of plant subterranean tubers, bulbs and rhizomes from botanical books and internet sources in order to enable us to match these with their indigenous “descriptor” names. Root foods that predominated in the traditional Noongar diet included yanjet (rhizomes of Typha, bulrush), borhn (and its variant names meernes, meen, madja red roots of Haemodorum), warrain (Dioscorea hastifolia, yam), karno (Platysace spp. native potato, youck), djubak (orchids), kara, djettah and others. The thick nutritious rhizomes of yanjet which provided an important seasonal source of carbohydrate are discussed in a separate paper https://www.anthropologyfromtheshed.com/typha-root-an-ancient-nutritious-food-in-noongar-culture

Djubak (djubok, jubuk, tuboc, tubac, tuubaq, tiupack)

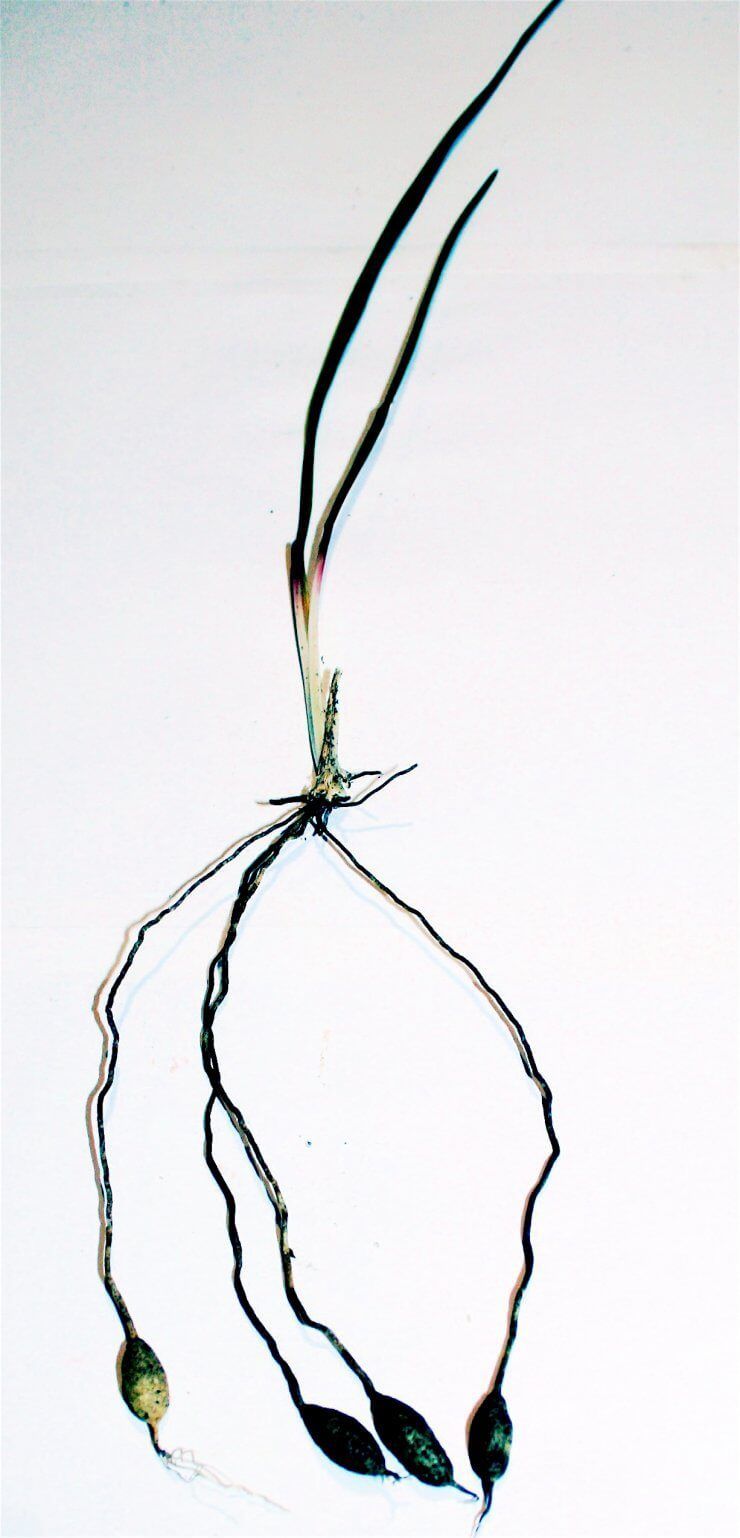

In Noongar taxonomy the edible orchid tuber known as djubak derives its name from its kidney shape (djubo or djuba, meaning kidney + ak, pertaining to) or, as Von Brandensten (1988: 165) describes it ‘little kidney’ tuubaq, orchid bulb’. These tubers were consumed in spring, according to ethnohistorical sources. For example, Collet Barker’s (1830) diary entries record Mokare consuming tiupuck in early October.

‘3 October …pointed out on the way the Tiupack in flower, a root much eaten by the Natives. It proves to be a kind of orchis.’ (cited in Mulvaney and Green 1992: 338)

‘6 October… Mokare made his appearance about 11 o’clock, seems somewhat better, had been living chiefly on Tiupuck since he was away.’ (cited in Mulvaney and Green 1992: 338))

Nind (1831: 35) describes how the stem and tuber of tuboc was consumed:

‘The tuboc is of the tribe Orchideae: it is very pleasant eating, when roasted. In the early part of spring it throws up a single stem, hollow, and similar in appearance to that of the onion, but is mucilaginous, and sweetish to the taste. This also is eaten. Before the young root comes to maturity it is called chokern, and is eaten raw: the old one is called naank.’

The term naank which generally denotes female or “mother” appears in this context to refer to the previous season’s tuber or “mother” tuber (what we call parent tuber). Chokern referring to the new season tuber is possibly a kinship or familial term denoting sister (jukan, chukan, chuker). Distinctions would have been made between the different life cycle stages of a food plant as this has implications for human consumption and nutritional value.

Nind’s (1831: 35) paper which was presented by the well-known botanist Robert Brown to the Royal Geographical Society in England identified tuboc to ‘probably a species of Thelymitra.’ Meagher (1974), however, re-classifies Nind’s (1831) tuboc to Prasophylum sp. based on the work of Drummond (the colonial botanist) who assigns tubac to Prasophylum giganteum (leek orchid). Bindon (1996: 208) in his book Useful Bush Plants follows Meagher’s (1974) species’ identification and attributes tuboc to Prasophylum sp.

Moore (1842) does not attempt to classify djubak to any particular species but describes it as:

‘An orchis, the root of which is the size and shape of a new potato, and is eaten by the natives. It is in blossom in the month of October. The flower is a pretty white blossom, scented like the heliotrope.’

Meagher (1974: 55) questioningly attributes Moore’s djubak to “?Prasophylum fimbria.”

Mulvaney and Green (1992:338) also attempt to identify tiupack to a Linnaean species:

‘probably the white mignonette-orchid, Microtis alba, which grows abundantly in the area, flowers in October with individual flowers clustered along the stem. However, the tubers are small. Alternatively, but less likely, this refers to the tubers of Microseris scapigera, the yam-daisy, which grew in the Albany district, although it has yellow flowers. It was a staple food in Victoria, where tubers gathered in spring do resemble small potatoes….[see B. Gott]’

Hammond (1933: 29) who does not attempt to identify to species describes “joobuck” as

‘…a white bulb with a long stalk. Some of the bulbs were as large as tennis balls, and they were very nice to eat.’

Djubak (or its variant spellings tuboc, djubuk, djubok, jubuk, tiupack, tiupuc and joobuck) has been applied to a wide variety of orchids, including the tuberous Pterostylis sp. (green hoods) and Pyrorchis nigricans (red beaks). Daw, Walley and Keighery (1997: 34) identify djubak to Burnettia nigricans (which is now known as Pyrorchis nigricans). They also note that the large tubers of the jug orchid (Pterostylis recurva) and sun orchid (Thelymitra species) were favoured.

In 1842 Drummond noted that:

‘…many of the Orchideae produce roots which are much sought after by them as food’ (Drummond 17th August 1842, Letter No.7).

Djubok (or djubak) is an indigenous body part metaphor referring to the often kidney-shaped tubers of these plants. The name collectively applies across a number of Linnaean defined species and genera including Thelymitra (sun orchids), Pterostylis (greenhoods), Prasophylum (leek orchids), Pyrorchis nigricans (red beaks), Microtis sp. and others. Aboriginal people often used local idioms and metaphors to convey information that would have been well understood by them at the local level.

It is interesting to note that the European term “orchis” or “orchid” itself derives from the ancient Greek term orkhis, literally meaning “testicle.” This is a body part metaphor referring to the appearance of the paired subterranean tubers (see Plate 2).

The Noongar used body part metaphors to describe aspects of their culture and natural topography, such as hills (katta also refers to head) and rivers and food resources. We have commented in our Acacia gum paper how the Noongar term badjong is a body part descriptor which likens the appearance of the gum of wattle to a pus oozing from a suppurating wound (see Plate 3 below) https://anthropologyfromtheshed.com/the-sweet-gum-a-nyungar-confection/

Kara (cara, karhrh, karr)

Indigenous plant names would have been collectively understood within the localised group. If plants shared similar and culturally significant characteristics, they would have been grouped together. This is probably the case with cara, which Drummond (1842) records as white edible roots. Drummond does not attempt to assign cara to any known species, nor does Meagher (1974:55). However, Pate and Dixon (1982: 220) and Bindon (1996:61) attribute cara to the swollen roots of Burchardia umbellata (now called Burchardia congesta). This plant grows on our property at Toodyay and it grew prolifically throughout the district after the Dec 2009 bushfire. When we showed the photograph below of the thickened roots of Burchardia (milkmaid) to Aboriginal Elders from the Perth area and asked them what they thought the name cara meant, they said :

“the tuberous roots resembled a spider (kara).”

Moore (1842) records karhrh as

“A tuberose root, like several small potatoes. It belongs to the Orchis tribe.”

Meagher (1974: 57) attributes Moore’s karhrh to Caesia species (see Plate 6 below). Bindon (1996: 62) also assigns karr to Caesia parviflora but he qualifies this by pointing out that:

‘The Aboriginal name for this plant is tentative, as there is some difficulty in separating references to Caesia spp. and Burchardia spp.’

Our research suggests that kara and karr are regional and dialectical variants of the same term which collectively refers to root vegetables that share similar characteristics in the indigenous plant food taxonomy. The terminally tuberous roots of Dichopogon sp. (see Plate 5) in many respects resemble those of Caesia (Plate 6) and are also known as karhrh. To the Western observer these root foods (Burchardia, Caesia, Dichopogon) may look different but within an indigenous utilitarian context they would have been grouped together if they were similarly identified, utilised and consumed, possibly at the same time of year.

According to senior Noongar spokespersons from the Perth area these types of root foods were generally consumed raw, had a crunchy texture and were often sweet and watery. Burchardia, Caesia and Dichopogon – kara and karhrh – may be found growing in a diversity of habitats, often in association with one another. Fire stimulates their growth and as we observed after the Dec 2009 Toodyay fire they were abundant throughout the district.

Karno (ganno, conna, kanna)

The terms karno, ganno, konno and conna have been recorded for different Platysace species (Meagher 1974, Pate and Dixon 1982 and Bindon 1996). One of these species Platysace cirrosa, sometimes referred to colloquially as the “round yam” (see Plate 7) is found in wandoo country near the base of Eucalptus wandoo where it thrives after fire. Drummond (who resided in Toodyay) records the indigenous name of its edible spherical tubers as “conna:”

‘large tuberous roots, sometimes 3-4 inches [7-10 cm] in diameter or more, the natives eat this root, which they call Conna, it is very juicy; the juice having a sweetish taste with a slight flavour of celery, the root seems to contain very little starch.’

We agree with Drummond’s description of taste. Bindon (1996: 202) describes the taste as ‘somewhere between that of coconut and carrot’ which is probably derived from Moore’s original description of taste:

‘I have discovered a bulbous root like a dark potatoe, called by the natives konno, which I mean to endeavour to cultivate, and which may be very useful if it succeeds. The taste is something like the meat of a cocoanut, or between that and a carrot taste. One specimen is as large as your fist.’ (July 1836 diary entry in Moore 1884: 301).

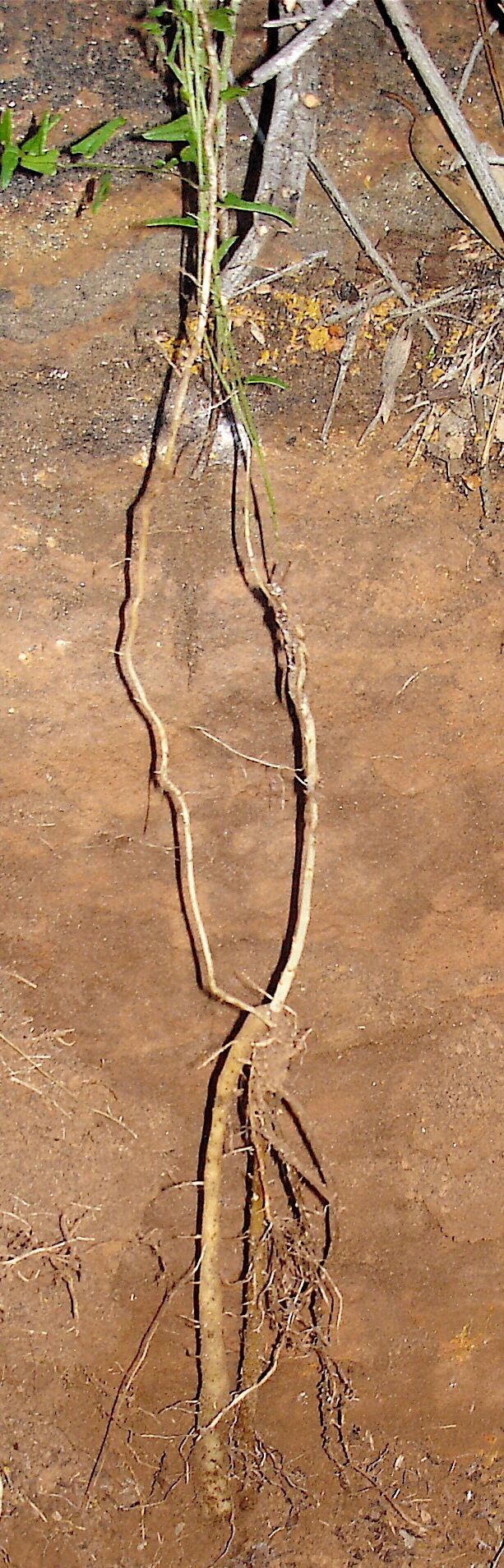

Pate and Dixon (1982: 220) note that the root tubers of P. cirrosa have a high water content but minimal protein and starch. The plant has a taproot system with round tubers spaced at intervals along it and these tubers increase in size as depth of soil increases. Drummond notes that the plant is largely invisible to the untrained European eye and that unless one knows what one is looking for, it goes unnoticed.

‘Slender, often inconspicuous herbaceous climber to 40cm tall.’ (Pate and Dixon 1982: 67)

Meagher (1974: 55) wrongly attributes Drummond’s conna to Eucalyptus wandoo but Drummond was referring to the wandoo habitat in which conna is found. The round tubers of P. cirrosa were consumed raw unlike the tubers of other Platysace species which were eaten raw or roasted. Pate and Dixon (1982: 220) identify the potato-like tubers which Ethel Hassell records as youcks (or youks, pp. 22 & 234) at Jerramungup to Platysace deflexa. However, Abbott (1983) identifies A.Y. Hassell’s yook to Platysace maxwellii.

Youcks – Platysace species

Hassell (1975: 23) describes the youks which were found at Jerramungup as follows:

‘Some were about as large as my thumb, some weighed quite three quarters of a pound, and they were a dull red colour. I carefully baked them, and don’t know when I enjoyed anything so much. They were sweet and watery, more like a yam than a potato and had a very thin skin which easily rubbed off. I tried boiling them but it was not a success for they were soft and watery and had very little flavour……..my husband drove me out to where there were quantities growing in reddish sandy soil. He told me the colour of the roots varied according to the colour of the soil they grew in, from red as I have seen them to pink and yellowish white. …The roots spread out some distance, and have to be followed up like sorrel roots to find the tubers at the end. They are in great demand with the natives and, where plentiful, they will camp near the patches until they are exhausted. The women with their wannas (sticks) dig long trenches to trace up the roots, and the places look as though a number of pigs had been routing about.’ (Hassell 1975: 23).

Youck – a sort of yam…..The plants are round, small, scrubby bushes about two foot high and have a small sage green leaf. The roots spread over a considerable area and have tubers at their extremities.’ (Hassell and Davidson 1936: 689)

Ethel Hassell’s youck (or youk) is spelt as yook by her husband A.Y. Hassell (see Bindon and Chadwick 1992: 192). Nind spells it as yoke and states:

‘They describe various kinds of roots in the interior which are eaten by them. One species they call yoke, and say that it resembles our potato, being as large and as well tasted, but it has only one tuber to a stem.’ (Nind 1831: 35).

Nind’s information about the yoke having only one tuber per stem would appear to be incorrect. Pate and Dixon (1982: 69, 220) have identified youck to Platysace deflexa which they say has ‘up to 30 tubers per plant.’

Identifying root foods to individual Linnaean species is always problematic because the Noongar had their own criteria and means of classifying plant foods which did not match the Linnaean speciation model. The Western botanical taxonomic structure does not fit the indigenous non-Western system of classification (Macintyre and Dobson 2017 unpublished notes).

Warrain (warran, woyay, wyrang, worrain, warrein, warrine)

Drummond (1842) describes the native yam as ‘the principal vegetable food of the natives’…. (Hooker, WJ. Journal Bot 2:355). He states:

‘The native Yam, called wyrang by the natives, the finest esculent vegetable the colony naturally produces is now beginning to flower [May]. It belongs to the class Dioeceoe of Linnoeus [sic]; the male is a yellow, sweet scented creeper, the female inconspicuous at this season.’ (4th May 1842, Drummond’s Letter No. 2 to the Inquirer).

Moore (1842: 75) describes “warran” as:

‘One of the Dioscorea. A species of yam, the root of which grows generally to about the thickness of a man’s thumb; and to the depth of sometimes of four to six feet in loamy soils. It is sought chiefly at the commencement of the rains, when it is ripe and when the earth is most easily dug; and it forms the principal article of food for the natives at that season. It is found in this part of Australia, from a short distance south of the Murray, nearly as far to the north of Gantheaume Bay. It grows in light rich soil on the low lands, and also among the fragments of basaltic and granite rocks on the hills. The country in which it abounds is very difficult and unsafe to pass over on horseback, on account of the frequency and depth of the holes. The digging of the root is a very laborious operation.’

Moore’s party when in the vicinity of Lennard’s Brook had to change their exploration route to avoid the hole-filled “yam grounds” which they observed on the alluvial flats and sides of the valley which were ‘so cut up into holes as to be almost impassable.’ The Noongar term garrabara which Moore translates as meaning ‘full of holes; pierced with holes’ may well describe the yam grounds after the digging season. Yams were cultivated by Noongar people, as evidenced by the records of the early explorers, settlers and historians. See our forthcoming paper on this.

Roth (1902: 48) describes the thick edible roots of the worrain:

‘Many kinds of roots and yams were eaten; among the latter the worrain showing thick yellow blossoms, was very common, growing down to a depth of quite 3 feet, and running from the thickness of the finger to that of the wrist.’

The paired stem tubers of warrain pictured below were observed in situ on our property at Toodyay. The new season’s tuber is shown on the left and the previous season’s tuber (parent tuber) on the right. The tuberous root measured approximately 30 cm long.

Bohn, borne, bhon (red roots), also known as meerne, meen, mean, mene, matje, madja, djakat, brigo, gwardyne, ngoolya, djanbar

‘7 or 8 species of Haemodorum together with the native Yam which is a true Dioscorea constitute the principal food of the natives in the way of vegetables; they eat the roots; all the species are mild and nutritious when roasted, but acrid when raw.’ (Drummond 1839)

Grey (1841, Vol. 2: 292) refers to the abundance of Haemodorum in the sandy soils around Perth:

‘…in the sandy desert country which surrounds, for many miles, the town of Perth, in Western Australia, the different species of Haemodorum are very plentiful.’

Drummond (1842) cites the famous botanist Dr. Lindley who in his letters declared the Swan River Colony the “headquarters” of Haemodorum:

‘Haemoraceoe of Brown, according to Dr. Lindley, have their headquarters on the West coast of New Holland…Dr Lindley appears to have seen only three from Swan River, but we have at least six distinct species [of Haemodorum]; the natives distinguish five of them by the following names:- Bhon, Madge, Quardine, Gnoally, Jagget, and there is another which I forget. The Bhon, is the root of Haemadorum Spicatum of Brown, and it is the plant alluded to by Dr. Lindley under Drosera, but it is a mistake; the natives do not use the roots of any species of Drosera as food. The Madje is the roots of Haemodorum Paniculatum, of Lindley, and Quardine, the roots of Haemodorum Planifolium [possibly Haemodorum laxum?]; the other I cannot refer, with certainty to any described species. The whole genus is of the greatest importance to the natives, for from any one or other of the species they can, at any time, and in any place, where they are likely to be, produce a meal of nutritious food with very little trouble.’ (Drummond, 10th August 1842, Letter No. 6 to the Inquirer).

The Noongar names bhon, madge, quardine, gnoally, jagget and in a later paper mynd (1862) are assumed by Drummond (1842, 1862), the first colonial botanist, to represent species of Haemodorum but he assigns only three to known species. This important traditional Noongar food source has been well documented by 19th and early 20th century recorders (Nind 1831, Collie 1834, Irwin 1835, Drummond 1839-1842, 1862, Grey 1841, Moore 1842, Backhouse 1843, Salvado 1851 in Stormon 1977, Lefroy 1863, Austin 1902, Hammond 1933 and Hassell 1936). All species had edible bulbs which were eaten sometimes raw but mostly roasted. The roasting in wood ash helped to remove the often bitter and hot peppery taste.

Grey (1841) records four different Noongar names for Haemodorum.: Mene, Ngool-ya, Mud-ja and Bohn whereas Moore (1842) records nine different names and Drummond (1842, 1862) lists six Noongar names. They all recognise that borhn is the common name for the edible roots of Haemodorum spicatum in the Perth/ Swan River region. In early accounts the term is also spelt as borhne, bohrn, bhon, borne and boon, depending on the individual recorder.

Some contemporary Elders that we talked to preferred to call it “borna.” (Macintyre and Dobson 2000 unpublished notes).

Moore (1842:12) describes bohn (or bohrn) as:

‘A small red root of the Haemodorum spicatum. This root in flavour somewhat resembles a very mild onion. It is found at all periods of the year in sandy soils, and forms a principal article of food among the natives. They eat it either raw or roasted.’

Moore (1842) records a number of names for these roots and interestingly uses bohn as a measure or point of reference against which to compare them:

mini – ‘An edible root. A large species of Bohn.’

djanbar – ‘’The same as the Madja, an edible root; a coarse kind of Bohn;’ (Moore 1842: 20)

brigo ‘An edible red root resembling the Bohrn’ (p. 14)’

djakat a type of Haemodorum (p. 109)

gwardyn ‘A root eaten by the natives; it somewhat resembles the Bohn, but is tougher and more stringy’ (Moore 1842: 34, 109).

ngulya – ‘An edible root of a reddish colour, something like Bohn in flavour, but tougher and more stringy’ (Moore 1842: 53, 109).

nguto – ‘resembling bohn’ (Moore 1842: 67, 109).

madja – ‘Haemodorum paniculatum, an edible root.’

Moore’s madja (1842: 47) is the same as Drummond’s madje (1842), Preiss’ matje (1839) and Grey’s mudja (1841, Vol 2:292). Preiss identified matje to Haemodorum paniculatum as early as 1839. It is possible that the term madja is a colloquial reference to the bulb’s edibility for Lyon (1833) records madya as meaning ‘mouth.’ Or its strap-like leaves may have been used as a rope or string, the term for which is madji (Moore 1842) or mudje (Grey1840:89).

ngool-ya – Drummond’s (1842) gnoally is equivalent to Moore’s ngulya and Grey’s ngool-ya. One could speculate that this name derives from the compound term ngool-boon-yer which Grey (1841) translates as meaning red or blood coloured. These plants are commonly known as “bloodroots” because of their distinctive blood red coloured roots.

djakat – is the same as Drummonds’ jagget and Nind’s choket. Nind refers to choket as

‘the small bulbous root of a rush; it is very fibrous and only edible at one season.’ (Nind 1831: 35).

bohn – The etymology of the term bohn is uncertain. We would suggest that it may derive its meaning from boorn. This term is also spelt boorne, poorne, poorrn, born, boon, boona) meaning tree, wood, stick or “stick of wood” depending on recorder. The erect flower stalk or woody spike (spicatum is its Latin species name) is a distinctive feature of this plant and after senescence when the plant enters into dormancy (summer) the “stick” is the only remaining visible indicator of the below ground food source.

Bunbury (1836) describes how his Noongar guide dug up some bulbs of Haemodorum for him to taste while travelling south of Perth. Bunbury’s diary entry on 23rd December 1836 states that Monang

‘dug up for me some red bulbous roots the name of which I have forgotten; in size & shape they are not unlike tulip roots but a light clear red colour & formed of distinct layers one above the other & all of the same color; the leaves are very long & narrow, but only two or three of them & I have never seen the flower; roasted they are mealy & very nice but when raw they are too pungent & biting, although crisp and with a very agreeable flavor.’ (Cameron and Barnes 2013:205)

In the Albany region the common name for Haemodorum spicatum is meerne (also spelt mearn Nind 1831), mene (Grey 1841), meen (Collie 1834), mini (Moore 1842), mean (Backhouse 1843), mynd (Drummond 1862) and mena (Lefroy 1863). This name is generally applied to H. spicatum in the southern parts of southwestern Australia, although Drummond, despite being the colonial botanist, does not identify mynd to species because in his mind he has already recorded bhon as the species name for Haemodorum spicatum. It was too confusing to the Western recorder for the same species to have more than one name.

Meerne is a collective term for “vegetable” (marrin or merin). For information on how the meernes were cooked and prepared using an earth additive, see our paper https://anthropologyfromtheshed.com/geophagy-the-earth-eaters-of-lower-southwestern-australia/

Djettah, jitta – round white tubers

jetta – ‘The root of a species of rush, eaten by the natives, in season in June. It somewhat resembles a grain of Indian corn, both in appearance and taste.’ (Moore 1842)

jitta – ‘The bulbous root of an orchis, eaten by the natives, about the size of a hazel-nut.’ (Moore 1842)

Drummond (1842) refers to ’round white roots called Jitta” and Hammond (1933: 29) describes ‘djettah’ as ‘a white bulb that grew in and around water holes.’ Bindon (1996: 254) identifies jitta to the tuber of Tribonanthes australis based on the work of Pate and Dixon (1982: 220) who in an earlier publication attributed djettah to Tribonanthes spp. However, we suggest a different identity for jitta.

‘We believe that jitta probably refers to the white round tubers of Bolboschoenus caldwellii (the common Marsh club rush) formerly known as Scirpus maritimus which grows on the margins of swamps and rivers and has tubers sometimes approximating the size of a walnut or small hazelnut, depending on seasonal factors (Macintyre and Dobson 2019).

Pate and Dixon (1982: 220 Table 5.11) record Scirpus maritimus and Tribonanthes spp. as both having a high starch content. According to their table S. maritimus contains three times the protein content of Tribonanthes spp. (i.e. 10.0 % compared to 3.2% in dry matter). The protein-containing tubers of S. maritimus (Bolboshoenus caldwelli) may be compared to those of Burchardia spp or“kara” which showed a high 12.4% protein (in dry matter).

Ecological and habitat descriptor names

Ecological/ habitat descriptor names sometimes indicate that plants share the name of a culturally valued insect, bird or animal that frequents the plant for feeding or breeding purposes. In our paper on Noongar insect husbandry we note that edible insect larvae known as paaluk were commonly found in the grass tree (Xanthorrhoea) which was also known as paaluck when it was in a dying or decaying state when its trunk provided the optimal breeding habitat for paaluk (a type of bardi) https://www.anthropologyfromtheshed.com/the-puzzle-of-the-bardi-grub-in-nyungar-culture

There are plenty of other examples of how the habitat of a culturally prized animal or insect food traditionally acquired the same name as the animal, bird or insect that frequented it. For example, the sandy habitat of the breeding burrowing sand frog called guyu (goya or kuya) is known as guyarra (or goyarra) referring to the sandy soil in which the burrowing frog lays its eggs in April/May. Another example of a habitat descriptor is the tammar bush which refers to the habitat of the small wallaby known as tammar that was traditionally hunted. Habitats often acquired the name of a culturally valued animal or plant that was harvested, hunted or collected there. In our Typha paper, we suggest that yanjet or yunjid the name of the carbohydrate-rich seasonal staple food traditionally consumed in autumn possibly derives its meaning from the freshwater habitat in which these bulrushes are commonly found. Grey (1840) records yunje as ‘a stream of running water’ and ‘a spring.’ Fresh water Typha swamps were once common in the Perth area before urban development took place. Another interpretation relates to the possible allusion of tufts of emu feathers (yanji) https://www.anthropologyfromtheshed.com/typha-root-an-ancient-nutritious-food-in-noongar-culture

Indigenous “descriptors” may describe any aspect of a plant such as its edibility, habitat, preparation, optimal time for digging or harvesting, life cycle stage, nutritive value or other usefulness, such as a medicine, artefact, shelter or bodily decoration. Sometimes indigenous descriptors reflect spiritual, totemic or mythological significance, such as mungite or Banksia nectar which according to Bates (1992) and Hassell & Davidson (1934:236-238) had totemic and mythological importance. As we have noted in our Banksia paper the term mangat or mangitch denotes the sweet taste of the nectar or sweet drink made from the nectar containing flowers. Names for Banksia include nugoo and bool-galla. Although these have been recorded as individual species’ names, they are really just descriptors. Nugoo refers to how the flowers were steeped in water to make a sweet drink. The term literally derives from nu-goo-lung ‘to steep in water’ (Grey 1840). See https://www.anthropologyfromtheshed.com/some-notes-on-banksia-usage-in-traditional-noongar-culture Banksia is also known as bool-galla. This literally translates as ‘many fires’ (boola, many or plenty + galla or kalla, fire), referring to the usefulness of the trees’ dead flower cones which were carried as smouldering fire sticks, especially by women under their booka (kangaroo skin cloak) for fire-making purposes, and also warmth in winter.

Conclusion

The Noongar people of southwestern Australia like other Aboriginal Australians evolved their own unique and independent scientifically-based, culturally relevant and adaptive system of plant and animal classification long before Europeans arrived in Australia. Indigenous “descriptors” were generally based on practical and utilitarian considerations that were appropriate to a hunter-gatherer- fisher-cultivator population. It is our belief that many of the explanatory “descriptors” recorded in the early part of the 19th century were an attempt by Noongar people to instruct the newcomers on the foods required to survive. The Noongar informants possibly assumed that the questions being asked of them about their plants were for the purpose of sharing their traditional knowledge of survival. If the recorders had understood what their informants were saying, this would have provided a valuable resource guide as to how and when these bush foods were identified, located, harvested and consumed. This descriptive vocabulary was a type of meta-language formulated in a simplified manner to familiarise the outsiders with the local food resources. Noongar people having been immersed in their local environment and its natural productions for many millennia would have had a much more subtle understanding and depth of knowledge of the seasonal indicators and complexities of their food resources than they are given credit for in the linguistic, ethnohistorical and anthropological records.

‘As Nyungar language and culture were based on oral tradition, all cultural knowledge had to be committed to memory through a combination of means including song, dance, chanting, story telling, poetic verse, totemic rituals and mythological narratives. Oral tradition necessitated an economy of words. Cultural constructs, knowledge and meaning were encoded into a system of mnemonics (key words, phrases or short verse) that helped to trigger memory processes and mental associations relating to essential knowledge embedded in the song-lines, totemic mythology and rituals. All of these mechanisms contributed to provide practical instructions on how to survive, economically, socially and culturally as a hunter-gatherer-cultivator people.’ (Macintyre and Dobson 2017)

This paper is based on research compiled over many years by research anthropologists Ken Macintyre and Dr Barb Dobson. The information derives from archival ethnohistorical sources as well as information sourced from contemporary Nyungar Elders and spokespersons. We would like to thank all Nyungar people (past and present) who over the years have assisted us by providing cultural information without which this paper would not have been possible.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abbott, I. 1983 Aboriginal names for plant species in south-western Australia.Forests Department of Western Australia.Technical paper No. 5.

Armstrong, F., 1836 Manners and habits of the Aborigines of Western Australia. From information collected by Mr F. Armstrong, Interpreter. The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal, Saturday, 5th November: 793–794.

Austin, Robert (see under Roth, W.E. 1902)

Backhouse, J., 1843 A Narrative of a Visit to the Australian Colonies. London: Hamilton Adams and Co.

Barker, Collet 1830 Journal. Available on Microfilm at the Battye Library, CSO Records. Perth. Original copy held at the State Library of New South Wales.

Barrett, R. and E.P Tay 2005 Perth Plants: A field guide to the bushland and Coastal Flora of Kings Park and Bold Park. First edition.

Bates, D. 1985. The Native Tribes of Western Australia. Isobel White (Ed.) Canberra: National Library of Australia.

Bates, Daisy 1992 Aboriginal Perth: Bibbulmun Biographies and Legends. Peter J. Bridge (Ed.) Carlisle, Perth: Hesperian Press.

Bindon, P. and R. Chadwick (eds.) 1992 A Nyoongar Wordlist from the South-West of Western Australia. WA Museum, Anthropology Department.

Bindon, P. 1996 Useful Bush Plants. Perth: Western Australian Museum

Bird, C.F.M. and Beeck, C. 1988. Traditional Plant Foods in the Southwest of Western Australia: The Evidence From Salvage Ethnography. In: Meehan, B. and Jones, R. (Eds.). Archaeology with Ethnography: An Australian Perspective. School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University: Canberra.

Brady, the Very Reverend J. 1845 A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Native Language of Western Australia. Rome: S.C. de Propaganda Fide. Typed Transcript at the Battye Library.

Brough Smyth, R., 1878. The Aborigines of Victoria. Melbourne: Victorian Government Printer.

Bunbury, W. St. P. and Morrell, W.P. (eds.) 1930 Early days in Western Australia, being the letters and journal of Lieut. H.W. Bunbury, 21st Fusiliers. London: Oxford University Press.

Bunbury, H.W. 1930 ‘Early Days in Western Australia.’ London: Oxford University Press. Journal entries for 1836.

Bunbury, H.W. 1836 Journal (see Bunbury and Morrell 1930)

Cameron, J. M.R. 2006 The Millendon Memoirs: George Fletcher Moore’s Western Australian Diaries and Letters, 1830-1841. Victoria Park: Hesperian Press.

Cameron, J.M.R. and P. Barnes (eds.) 2014 Lieutenant Bunbury’s Australian Sojourn: the letters and journals of Lieutenant H.W. Bunbury, 21st Royal North British Fusiliers, 1834-1837. Victoria Park, WA: Hesperian Press.

Clark, Dymphna (translator and editor) 1994 Baron Charles von Hugel New Holland Journal, November 1833-October 1834. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press at the Miegunyah Press in association with the State Library of New South Wales.

Collett Barker (see under Barker 1830)

Curr, E.M. 1886 The Australian Race: Its origin, languages, customs, place of landing in Australia, and the routes by which it spread itself over that continent. Vols. 1 & 2. Melbourne: Government Printer.

Daw, B., Walley, T. and Keighery, G. (1997). Bush Tucker Plants of the South West. Department of Conservation and Land Management, Western Australia.

Dench, A. 1994 ‘Nyungar’ in Thieberger, N. and W. McGregor Macquarie Aboriginal Words. Sydney: Macquarie University, New South Wales.

Douglas, Wilfred. H. 1976 The Aboriginal Languages of the South-West of Australia. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. Second edition.

Drummond, James 1836 Correspondence to the Editor. Published 18th June in The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal, p 710.

Drummond, J. 1839 Letter to Sir William Jackson Hooker, Kew Gardens, London. Written from Hawthornden Farm, Toodjey Valley. July 25.

Drummond, J. 1839 Letter to Sir William Jackson Hooker, Kew Gardens, London. Written from Hawthornden Farm, Toodjey Valley. October 14.

*Drummond, J. 1842, Letter No. 2 to the Inquirer, 4th May.

Drummond, J. 1842 Letter No. 6 to the Inquirer, 10th August.

Drummond, J. 1843 Letter No. 15 to the Inquirer, 22nd March.

Drummond, H. 1862. ‘Useful plants of Western Australia.’ The Technologist 2: 25–28.

Gammage, B. 2012 The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Gott, B. 1982 ‘Ecology of root use by the Aborigines of southern Australia.’ Archaeology in Oceania, 17, pp. 59-67.

Green, N. 1979 Nyungar – The People: Aboriginal customs in the southwest of Australia. Mt Lawley, North Perth: Creative Research Publishers.

Grey, G., 1840 A Vocabulary of the Dialects of South Western Australia. London: T. and W. Boone.

Grey, G., 1841 Journals of Two Expeditions of Discovery in North-West Australia. London: T. and W. Boone.

Hallam. S.J. 1975 Fire and Hearth a Study of Aboriginal Usage and European Usurpation in South Western Australia. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. First edition.

Hallam, S. J. 1991 ‘Aboriginal Women as Providers: the 1830s on the Swan’ Aboriginal History, Vol. 15. Part 1. pp. 38-53.

Hallam, S.J. 2002 ‘Peopled landscapes in Southwestern Australia in the early 1800’s: Aboriginal burning off in the light of Western Australia historical documents.’ Early Days: Journal of the Royal Western Australian Historical Society, 12, 2: 177-191.

Hammond, J.E., 1933 Winjan’s People. Perth: Imperial Printing Co.

Hassell, A.Y. 1894 Notes and family papers. Manuscript. Perth: Battye Library.

Hassell, E.A. 1880-1890’s Notes and family papers. Perth: Battye Library. Handwritten manuscript.

Hassell, E., 1936 Notes on the ethnology of the Wheelman tribe of Southwestern Australia. Anthropos 31: 679–711.

Hassell, E., 1975 My Dusky Friends. Dalkeith: C.W. Hassell.

Hercock, M. Milentis, S. and P. Bianchi 2011 Western Australian Exploration 1836-1845: The Letters, Reports and Journals of Exploration and Discovery in Western Australia. Victoria Park, WA: Hesperian Press.

Lyon, R.M. 1833 ‘A Glance at the Manners, and Language of the Aboriginal Inhabitants of Western Australia; with a short vocabulary.’ 23rd March in N. Green (ed.) 1979 Nyungar -The People: Aboriginal customs in the southwest of Australia. Perth: Creative Research.

Macintyre, Dobson and Associates 2003 Report on an Ethnographic, Ethnohistorical, Archaeological and Underwood Avenue Bushland Project Area, Shenton Park. A report prepared for the University of Western Australia.

Macintyre, K. and B. Dobson 2008 Notes on Noongar taxonomy and nomenclature. Unpublished.

Madden, R.R. 1848 Vocabulary of the Aborigines, Perth Tribe Dialect (microfilm). Battye Library, Perth, Western Australia.

Meagher, S.J., 1974 The food resources of the Aborigines of the south-west of Western Australia. Records of the West Australian Museum 3(1): 14–65.

Moore, G.F. 1835 ‘Excursion to the Northward’ from the journal of George Fletcher Moore. Esq.’ Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal, 26 April and 2 May 1835; also reprinted in J. Shoobert (ed.) 2005 Western Australian Exploration Volume 1: 1826-1835. Victoria Park: Hesperian Press pp. 421-427.

Moore, G.F., 1842 A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Language in Common Use Amongst the Aborigines of Western Australia. London: W.S. Orr and Co. Hard copy.

Moore, G.F., 1842 A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Language in Common Use Amongst the Aborigines of Western Australia. Online source.

Moore, G.F. 1884. Diary of Ten Years of Eventful Life of an Early Settler in Western Australia. London: M. Walbrook.

Mulvaney, J. and N. Green 1992 Commandant of Solitude: The Journals of Captain Collet Barker 1828-1831,Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press.

Oldfield, A. 1865. On the Aborigines of Australia. Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London 3: 215–298.

Pascoe, Bruce 2014 Dark Emu: Black seeds agriculture or accident? Broome: Magabala Books.

Pate, J.S. and K.W. Dixon. 1982. Tuberous, cormous and bulbous plants: biology of an adaptive strategy in Western Australia. Perth: University of Western Australia Press.

Roth, W.E. 1902 ‘Notes of savage life in the early days of West Australian settlement.’ In Royal Society of Queensland. Proceedings, vol. 17:45-69. Based on reminiscences collected from F. Robert Austin, Civil Engineer, late Assistant Surveyor, W.A. (1841). Paper read before the Royal Society of Queensland 8th March 1902.

Salvado R., 1851 in E.J. Stormon 1977 The Salvado memoirs: Historical memoirs of Australia and particularly of the Benedictine Mission of New Norcia and of the habits and customs of the Australian natives. By Rosendo Salvado, translated and edited by E.J. Stormon. Nedlands: University of Western Australia Press.

Sharr, F.A. 1996 Western Australian plant names and their meanings: a glossary. Nedlands: University of Western Australia Press.

Shoobert (ed.) 2005 Western Australian Exploration 1826-1835, The Letters, Reports & Journals of Exploration and Discovery in Western Australia. Vol 1. Victoria Park: Hesperian Press.

Stokes, J.L., 1846. Discoveries in Australia; With an Account of the Coasts and Rivers Explored and Surveyed During the Voyage of the H.M.S. Beagle in the years 1837–43. London: T. and W. Boone.

Stormon E. J. 1977 The Salvado Memoirs. Nedlands: University of Western Australia Press.

Symmons, C. 1841 Grammatical introduction to the study of the Aboriginal language of Western Australia. Perth: Western Australia Almanac.

Thieberger, N. and McGregor,W. Macquarie Aboriginal Words. Macquarie University, New South Wales.

Von Brandenstein, C. G. 1988 Nyungar Anew. Pacific Linguistics, Series C – No. 99. Department of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University.

Von Hugel, Baron Charles 1833 in Clark, D. (translator and editor) 1994 New Holland Journal November 1833-October 1834. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press at the Miegunyah Press in Association with the State Library of New South Wales.

White, I. (Ed.) 1985 The Native Tribes of Western Australia. Canberra: National Library of Australia