Kudjil the Crow man at Cottesloe

In an earlier paper here, we talked briefly about a notorious historical character by the name of Johnny Cudgel whose epic story merged with the pre-existing narrative of the ancestral Crow man at Mudurup (now Cottesloe).

In early times the ancestral totemic crow/crowman was the over-arching mythology of the coastal strip at Mudurup. The traditional belief was that crows (wardung, wardong) were the messengers of the rain beings, thunder beings and the wind. Only a powerful sorcerer, such as the Crow man, could divine the subtle unpredictability of these natural elements. When storms approached, the Crow man would announce its coming to his ‘dark moiety’ kinsmen, the loud screeching oolynark (white-tailed black cockatoos) and excite the busy movements of the biddit (ants). These would indicate to Aboriginal people the coming of stormy weather.

As the story goes the “Crow man” was a powerful bulya-gadak (sorcerer) who could control the thunder and wet weather elements (storms, rain) together with the seasonal movement of fish along the coast. This powerful bulya-man had the ability to shape-shift from human form to that of a raven (commonly called “crow”) and vice versa. Culturally the raven was the pre-eminent symbol of the ‘dark season’ and gave its name to the ‘dark moiety’ known as wardongmat (wardong, crow + mat, stock, family). This was one of the two principal divisions of Noongar society. The other division representing the ‘light moiety’ was known as manitchmat (manitch, white cockatoo + mat, leg, stock, family).

In traditional belief high-ranking sorcerers or bulya-men could metamorphose into animals or birds, such as the crow or owl. Elders suggested to us that crow behaviour was often seen as a sign of changing weather patterns channelled through the ancestral Crow man. One of the key functions of the coastal bulya-man or “clever-man” (as he is now sometimes called) was the divination of weather and the prediction of fish behaviour. His forecasts were critical to the economic survival of the coastal fishers. The Crow man’s “run” or territory, according to Noongar Elders, was between Wadjemup (Rottnest) and the coast of Mudurup (Cottesloe).

With the expansion of beachside settlement at Cottesloe in the late 19th century the traditional habitation and movement of Aboriginal people was increasingly restricted and regulated by the government authorities, local and State. It was within this environment that the new culturally-adapted narrative – the story of Cudgel – emerged. He was a “clever man” – a larger than life character – whose story was told to us by former residents of the Swanbourne fringe camp.

These Elders remembered stories told to them by ‘the old people’ around the fire at night about Kadjil’s (Cudgel’s) miraculous escape from Rottnest Island. There was no doubt in their minds that this story was true and that Johnny Kadjil (or Cudgel) had indeed landed in the semblance of a crow on a beach not far from the (then) Swanbourne camp. In another version of the story we find him as the Crow man camped in a cave at Mudurup Rocks performing sacred ceremonies.

We could find no documented evidence of Cudgel’s escape from Rottnest. However, the Swanbourne fringe camp-dwellers and their descendants were (and still are) convinced by the oral history passed down to them that Kadjil’s spirit had escaped and visited his people in the guise of a crow. By the 1920’s Cudgel had become a legendary character of Noongar folk mythology. It is not difficult to imagine how such a powerful contemporary folk hero as Cudgel rejuvenated the traditional narrative of what is now known as Kudjil (or Kadjil) the Crow man (https://anthropologyfromtheshed.com/project/ethnography-of-mudurup-rocks-in-cottesloe-and-its-connection-to-rottnest-island-wadjemup/)

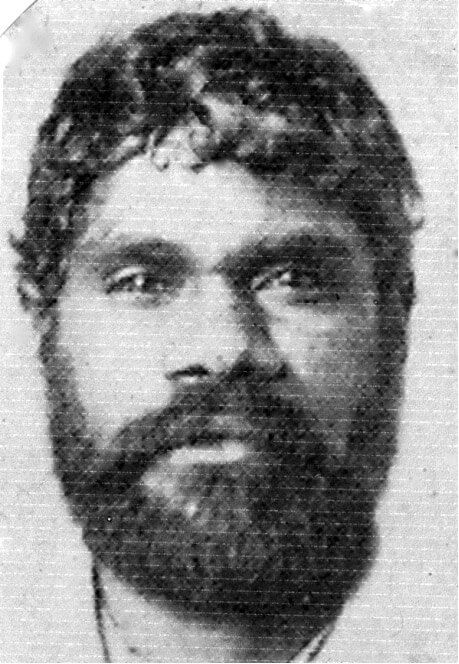

Similar stories of the ‘clever man’ Johnny Cudgel were related to us by Elders from the Albany, Busselton and Pinjarra areas. These stories, which they had heard as children from their senior relatives, confirmed Cudgel as a legendary bulya-man challenging and outwitting white authority. The name Cudgel is variously rendered in historical sources as Cudgin, Cudgen, Cadgill, Cadjill and Cudgell. Daisy Bates records his name as Kujjal (also Gidjup). Cudgel authored his own letters (1914) and paintings (1917) as “John Cudgel.” The name Kudjil (also spelt Kadjil) was used with reference to the Crow man story told to us by Mr Corrie Bodney (personal communication 1993) who had heard the story from his senior relatives as well as from Sam Broomhall who, although not a Noongar, had lived in the Swanbourne area since his release from Rottnest Island.

The early Albany Police Court Records refer to Cudgel as Cudgen (cited in the Australian Advertiser 2/5/1892) whereas later police records identify him as Cadgill (cited in the Australian Advertiser 10/8/1892). Cudgen may have been his Aboriginal name or a nickname. It comes very close to kadjin (or kadgin, kadgeine or cachin (Curr 1886) a term which translates as ‘ghost’ or ‘spirit’ (see Symmons 1841: 25 and Moore 1842:38). It is not hard to imagine that Cudgen was a nickname referring to his fleetness of foot and ability to disappear from authority in the blink of an eyelid, or as the Truth (14/5/1904) portrayed him:

‘Johnny Cudgell, a notorious Albany blackfellow, was consigned to the local jimbo the other day under remand on a charge of stealing. The lock-up keeper forgot, however, to plug up the keyhole at night, and found next morning that Johnny had crawled through and escaped. Police haven’t seen him since, and are not likely to.’

An article in the Daily News (July 1904, page 1) referring to Johnny Cudgel’s escape states:

‘He was lodged in the Albany lock-up pending trial, but somehow managed to elude the vigilance of his captors and effected his escape.’

The newspaper accounts which commonly referred to him as “Cudgel” tended to promote and even embellish his almost supernatural feats. He became well known throughout the southwest for his escapades and notorious and heroic exploits. One of these sources, the Sunday Times, dramatised him as being one of Western Australia’s most notorious Aboriginal bushrangers who made a mockery of police by escaping from their custody, outsmarting them and leading them in circles around the country. In 1905 while incarcerated at Rottnest Island, Cudgel heroically saved the life of a white prisoner caught in dangerous rocks and surf off the west side of Rottnest. Although he was highly praised by prison authorities, and also by the Comptroller-General of Prisons, Mr Oct. Burt, for his bravery, he was refused an award from the Royal Humane Society on the grounds that the Society did not give awards to prisoners (Western Mail 1905).

Cudgel was the embodiment of Noongar defiance against white oppression. His name according to official records was John Gidgup but he was generally known by and preferred the name “John Cudgel” or “Johnny Cudgel.” His escapades are well recorded in the early newspapers:

In 1892 at the age of 18 Cudgel received heroic newspaper coverage of his daring escape during a violent storm from the lighthouse on Breaksea Island off the coast of Albany where he had been billeted on work duties. By the early part of the 20th century Cudgel had become a media star, a black bush ranger and a folk hero to the oppressed Nyungar people of southwestern Australia. Stories of his uncanny ability to escape from the custody of Her Majesty’s gaols abounded within the community to the point where his feats became seen as superhuman, not to mention his perceived ability to transform himself into a crow and mysteriously escape across the sea from the notorious Rottnest Island prison (https://anthropologyfromtheshed.com/project/ethnography-of-mudurup-rocks-in-cottesloe-and-its-connection-to-rottnest-island-wadjemup/)

Cudgel was renowned for his daring deeds and heroic actions and was in some respects a role model to other Aboriginal people as he defiantly stood up for his rights to be regarded as an equal to the white man. There is no doubt that the story of Cudgel or Kudjil the Crow man has its roots in the earlier mythology of the ancestral totemic Crow man. The contemporary story of Cudgel (Kudjil) is a good example of narrative syncretism whereby an indigenous story adapts to a changing social, cultural and political environment.

Johnny Cudgel was an inmate of the Rottnest Island gaol on and off between 1890 and 1925. Although we could find no documented evidence of Cudgel’s escape from Wadjemup, there was no doubt in the minds of the Swanbourne fringe dwellers and others that he had escaped imprisonment on the island in the guise of a crow.

These traditional and contemporary stories of the “Crow man” were collected from senior Noongar Elders who as young people had resided with their families in the fringe camps at Swanbourne and Claremont. Their information derived from stories they had heard from their parents and other relatives and residents of the fringe camps. Information was also obtained from senior Noongar spokespersons residing in Perth, Albany, Busselton and Pinjarra who were familiar with the story of Kudjil (Cudgel) the clever man and his notorious feats.

There may be other versions of the Cudgel story that we are not aware of which other senior Noongar people may have heard as children when growing up in fringe camps in southwestern Australia. The story of Cudgel was one of hope and defiance against white oppression. This story is relevant to all Noongar people even to this day and especially members of the Gidgup family.