The ancient practice of Macrozamia pit processing in southwestern Australia

Prepared by Ken Macintyre and Barb Dobson

Research anthropologists

Introduction

Why did Noongar people ferment Macrozamia sarcotesta? Was it to detoxify it?

It is our view that over many thousands of years of trial-and-error and empirical scientific observations that Noongar people developed their own unique and sustainable food processing techniques, in particular the controlled anaerobic fermentation of the fruit (seed covering, outer rind) of Macrozamia to enhance its taste and nutritive value and to make it easier to remove from the seed which was not eaten. We could find no scientific evidence in the archaeological or ethnohistorical literature, apart from the untested assumptions of Grey (1840, 1841) and Moore (1842), that the Noongar people traditionally processed the Macrozamia sarcotesta for the purpose of detoxification. We question this assumption that has been perpetuated in the literature even to this day.1

The Noongar of southwestern Australia are unique in that they were the only Aboriginal group in Australia that consumed the processed red fruit sarcotesta of Macrozamia. Their methods of soaking and/or burying the fruit can, in our opinion, best be described as a process of “fermentation.” By contrast Aboriginal groups living in Eastern Australia consumed only the processed seed (starchy endosperm) and discarded the oil-rich sarcotesta.2 We have always been curious as to why Noongar people traditionally fermented and consumed only the sarcotesta. Was their unique method of anaerobic fermentation an adaptation to the water-scarce environment of southwestern Australia at the time of harvest (late summer/ autumn) or was it their specialised scientific knowledge that fermentation improved the taste and provided a valuable source of high energy fat and nutrition (e.g. vitamin A)?

Certain early African populations of hunter gatherers (such as the San and the Hadza) are starting to be recognised for their unique and highly diverse gut microbiome which has enabled them to consume a wide range of bush foods found only in their localised environments. Similarly, we maintain that Noongar people must have evolved these specialised adaptations in their gut biome that enabled them to digest and store quantities of fats and fat-soluble vitamins (such as Vitamin A and D) which derived from foods rich in beta-carotenes such as the Macrozamia sarcotesta. Their gut microbiome would also have adapted over time to tolerate any bitter-tasting or toxic residues that may have been present in their plant food sources. We do not discount the possibility that if there were any residual traces of glycosoides (such as cycasin or macrozamin) remnant in the sarcotesta after processing (either from residual toxin or oil rancidity) that these would have been tolerated without inducing ill-effects.

Traditionally bayoo was always processed prior to consumption

This highly prized seasonal food source was traditionally known as baio (Moore 1835) or bayoo (Bunbury 1836). It is also variously rendered in the ethnohistorical literature as baayoo, baio, by-yu, boya, boyern, boyah, boy-oo, poio or boy, depending on recorder and geographic region. These variant terms may be interpreted in a number of ways, depending on context. We suggest they may allude to fat, egg or stone.

Ngilgee one of Daisy Bates’ informants from the Vasse area records the name of this food as baian (Abbott 1983: 6). Whitworth (n.d) records the name of the palm as boyern and the linguist Von Brandenstein (1988: 51) renders the ‘Zamia palm nuts or seeds’ as pauyin. We would suggest that these are synonymous terms alluding to the fat-rich flesh or fruit of the Zamia. The term boyan and its variants boin, boyn, boyne or boyn-yer translate as oil, fat or grease and boyu according to Brady (1845: 16) means ‘fat.’

Whitworth (n.d: 15) records the name of the fruit of the Zamia as “boy-ya” and he also lists the term for egg as boy-ya. Ngilgee (n.d: 3) records “buoya” as ‘bird’s egg.’ It is highly probable that the term by-yu (or its variant spellings poio, boy-ya, boyah, by-yoo, by’yoo, boy) alludes to egg (bwye, pooyiore, boy-ya, buoya) that in this context is incubated (underground) to become a rich source of fat. The seeds could be described as ovoid or egg-shaped. The term may even be a biological referent to the propagative ovules or seeds of the Macrozamia which fall to the ground from the female cone when ripe and ready for dispersal.

Were the indigenous informants possibly using a descriptor name by-yu to refer to the fat-rich ovoid egg-like fruit (pooyiore, bwye “egg”) or seed?

Another translation is “stone” for as noted by Bindon and Chadwick (1992: 396) boye, booy, booi, pwoy, poya, pooi, boyee, boya mean ‘stone’ or boyer “little stones” (Bussell n.d.).

Bussell (n.d.) records the Noongar name for the ‘native palm’ (“zamia”) as “biana.” This may be a descriptor explaining how the fruit was buried for Moore (1842:10) translates bian as ‘to dig’ or ‘to bury’ or past tense biana. We think Bussell’s informant was probably explaining how the food was prepared. Descriptors were commonly used to describe how plants were identified, prepared, consumed or otherwise used.

Djiriji – a totemic name for the Macrozamia palm?

A common name for the Macrozamia plant in the Perth and surrounding area is djiriji (Moore 1842: 30), dyergee (Lyon 1833), girijee “(“the Zamia tree,” Grey 1840: 42), dji-ri-ji (Symmons 1841), djir-jy (Stokes 1846) or jeerja (Joobaitch, Daisy Bates’ informant). Possibly this name has mythological significance. It may even be a totemic referent deriving from the association of Macrozamia with a version of the fire-recapture mythological narrative.

In one version of this myth, the hawk, after retrieving the nut containing the fire from the bandicoot, drops it into the zamia plant where it ignites the highly flammable woolly kundyl. According to Noongar spokespersons, when we asked them about this myth, they said that the bright red seeds of the zamia give the illusion of fire. They agreed that djiridji was probably a totemic name that may have been connected to this fire-retrieval story. We think that the term djiriji is probably a linguistic derivative of the term jir-e-git that was recorded by Grey (1840:55) as meaning “sparks” or by Moore (1842: 159) as girijit “sparks of fire” – a metaphorical reference to the resemblance of the red seeds to burning embers.

Macrozamia fruit are known as quinine or quenine in the southern region

In the southern region the Macrozamia fruit was commonly known as quinine or quenine (Barker 1830), also spelt gwineen (Grey 1840: 48), kween-een (Grey 1840:72), kwinin (Moore 1842: 64), quinning or quinelup, (A.Y. Hassell 1894).

Barker, who was recording aspects of Aboriginal culture in the vicinity of King George Sound in 1830, was the first European to record the indigenous name for the fruit of the Zamia. He notes in his diary on January 9th 1830:

January 9 ‘Quinines not yet ripe.’

When exploring north of Cape d’Entrecasteaux and the Nornalup area, he writes:

‘This is the great country for ‘Quinine,’ the fruit of the low fan leaved palm which after gathering they bury in the earth for about a moon when it becomes fine eating. The country here is very populous and the people fat but he [Marignan] and others describe the soil to be poor & sandy.’ (Barker 1830)

Barker (1830-1831) provides the earliest documented reference to the processing, storage and consumption of quinine (Macrozamia fruit) in southwestern Australia. He views these underground repositories of quenine as a form of food provisioning:

‘This is the great country for Quenine, which after gathering, they bury in large store in the ground & in about a moon it becomes fine eating. This is the first instance of any provision of food which I have heard of them.’ (Barker 1830)

-

Button

Plate 4: Bayoo fruit after soaking and burying. Photo by Ken Macintyre 2009

-

Button

Plate 5: Bayoo fruit after soaking in saline water. Photo by Ken Macintyre 2009.

-

Button

Plate 6: Field sketch by Ken Macintyre (2007) showing sarcotesta (outer portion, seed coat) that is consumed by Noongar people after processing.

-

Button

Plate 7: The oil-rich sarcotesta after processing. Photo by Ken Macintyre 2009.

Noongar people ate only the processed sarcotesta, not the seed kernel

There is much confusion to this day, especially on the numerous “bush tucker” internet sources, as to which part of the Macrozamia fruit was consumed after processing by Noongar people. The traditional practices used by the Noongar often get confused with the methods used in Eastern Australia where only the starchy seed or endosperm was processed and eaten.2

‘Macrozamia nuts leached and baked, were the carbohydrate staple all down the east coast of Australia’ (Rhys-Jones 1978).

In contrast the Noongar consumed only the processed outer rind or seed covering known as the sarcotesta:

‘Only the fleshy part, which resembled a tomato in colour and taste, was eaten. The nut was not eaten.’ (Hammond 1933:28)

It is unclear from the ethnohistorical records when the Noongar stopped using this processed food source. The last recorded observation that we could find was by Edwards, a veterinary surgeon employed by the W.A. Bureau of Agriculture who in 1894 reported that Noongar people were still processing Macrozamia fruit which they called boyah. He describes how during the fruiting season he observed seeds that were soaked “in shallow brooks” and also sometimes in bags ‘suspended by a string attached to a stake on the sea beach.’

Both Edwards (1894: 233) and Hammond (1933: 28) describe salt water being used in the preparation of boyah or boyoo. This practice is consistent with contemporary anecdotal accounts provided by informants of Macrozamia fruit having been soaked in water in wheat or chaff bags in the late 19th /early 20th century. According to one Noongar spokesman, Mr William Warrell, the “bo-yu” were placed in an old wheat sack with a few heavy rocks to weigh it down and a rope was then tied around the opening to ensure the seeds did not float away. The end of the rope was tied to a tree or stake to secure it. When we asked for how long this was done, he said he had no idea how long the seeds were left to soak, maybe about two weeks, he thought. He remembered being told this information by his grandmother Ollie Warrell who must have observed the activity when growing up.

Traditionally the ripe fruit were collected by Noongar women around March and transported in their goto (kangaroo skin bags) to the nearest processing location. These bases would have depended upon the availability of water which by the end of summer was mostly brackish or saline. Soaking pools were sometimes constructed on the edge of waterways but great care would have been taken not to contaminate the already limited drinkable water supplies. When water was scarce or not available the by-yu were buried for a number of weeks without soaking. These burial pits provided a form of hidden storage.

It was important that we reconstruct the method of how Macrozamia fruit was processed

In 2008 and 2009 we attempted to replicate traditional bayoo processing methods, in accordance with how they have been described in the ethnohistorical literature by Barker (1830), Moore (1835), Bunbury (1836), Drummond (1839), Grey (1840, 1841), Backhouse (1843) and Hammond (1933). The purpose was to gain an insight into how and why the fruit was soaked and/or buried for a certain period by Noongars prior to consumption.

Our archival research, practical experiments and consultations with Noongar Elders over a number of years together suggest that the Macrozamia fruit was processed using ancient indigenous cultural techniques and scientific knowledge to enhance the taste, texture and nutritional value and most importantly to enable the fruit to be easily removed from the seed. An added advantage may have been the ability to store and preserve this highly coveted food for a limited time.

In 2009 the Chem Centre WA carried out an analysis of the sarcotesta samples that we provided to them, prior to and post-processing, and the results of these tests are presented in our separate paper available here.

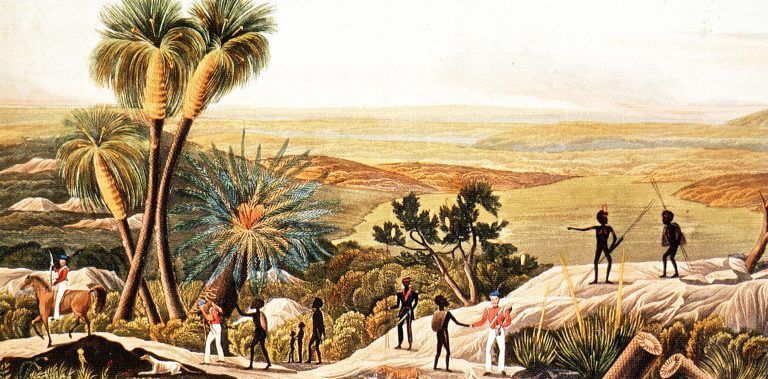

To this day archaeologists, ecologists, historians and anthropologists maintain that Macrozamia sarcotesta was processed by Noongar people primarily for detoxification purposes. We suggest that this untested assumption derives from the early reports of Europeans who became violently ill from consuming unprocessed (or insufficiently processed) Macrozamia “nuts.” Moore (1835), Drummond (1839) and Grey (1840, 1841) have all referred to the need to detoxify the sarcotesta of the Macrozamia seed prior to consumption to avoid ill-effects. The earliest recorded account of European poisoning from the consumption of Macrozamia ‘nuts’ dates back to Vlamingh’s expedition in the Swan River area in 1697.

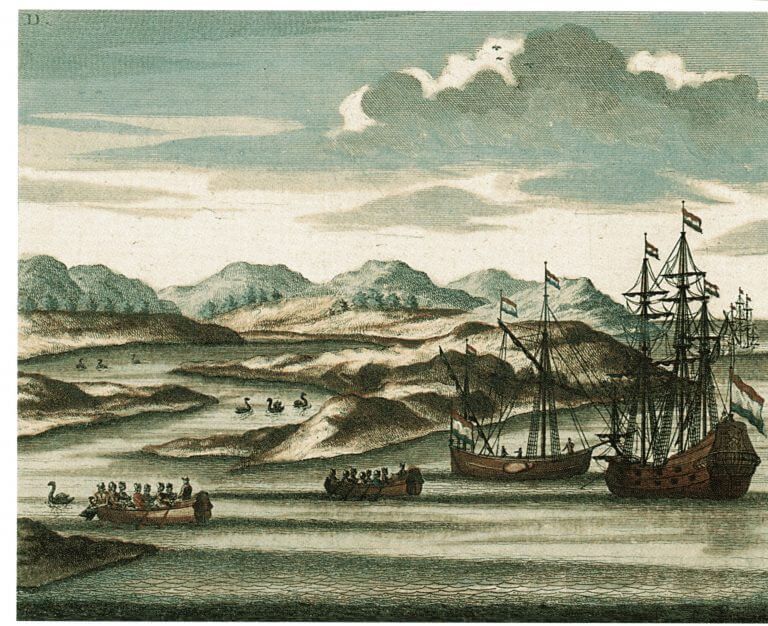

Earliest Macrozamia nut poisoning: the Vlamingh Expedition at the Swan River

Prior to European colonisation of southwestern Australia the early Dutch explorers to the Swan River were experiencing first hand the ill-effects of consuming Macrozamia nuts. It is easy to imagine how these Dutch explorers assumed that these large chestnut like “nuts” (see Plate 9) which they found lying around Aboriginal campsites were an edible food source consumed by the local inhabitants. We suspect that the Dutch were eating de-fleshed Zamia seeds left-over from a previous season for they describe them as a yellow-brown colour. It is unlikely that the Dutch ever observed or consumed ripe Macrozamia fruit for at the time of their exploration of the Swan River area in early January 1697, these fruit would have been green, unripe, probably toxic and tightly compacted into the female cone or strobilus (see Plate 10).3

-

Button

Plate 9: Note the resemblance between the light coloured Macrozamia nuts and the darker chestnuts to which they were often compared by early explorers. Photo by Ken Macintyre.

-

Button

Plate 10: The large pineapple-like cone of a female Macrozamia plant. Unripe (January 2010). Is this similar to what the Dutch encountered at the Swan River in January 1697? Drummond (1842) refers to the female cone as being four times the size of the male cone. Also, Von Huegel (1833 in Clark 1994: 28) describing his first encounter with the “Zamia” at the Swan River comments: ‘I was astounded by the huge fruit of the Zamia. They grow fairly close together here and several had more than one spike of fruit each weighing between 40 and 50 pounds.’ 4 Photo by Barb Dobson.

One of the Dutch officers describes in his diary (6th January 1697) how he and five other members of the Vlamingh expedition suffered the dire consequence of eating these fruits:

‘I ate five or six of them, drunk the water from one of the already mentioned pits [this is presumably a reference to a freshwater soak near the river]; but after about three hours I and five others who had eaten of these Fruits, began to vomit so violently that there was hardly any difference between us and death; so it was with the greatest difficulty that I with the Crew reached the shore… “(cited by Robert, 1972: 23)

Hamilton and Bruce (1998: 50) cite Witsen, one of the Vlamingh crew, as describing the fruit (or cone?) of the Zamia [probably Macrozamia fraseri] as closely resembling:

‘…our local scarlet beans, the colour being between yellow and white: these beans contain a nut which is not unlike the chestnut and is not unappetizing, but causes a vertigo in the head which resembles madness, for the mariners who tasted of them crawled on the ground and made senseless gestures, which lasted for two days.’

We can only assume that the fruits consumed by the Dutch were the chestnut-like de-fleshed seeds that may have been previously processed and discarded by the local indigenous inhabitants.5 These seeds would have lost some of their toxicity as a result of anthropogenic fermentation, natural ageing and weathering and these combined processes may have accounted for the survival of the officer who consumed 5-6 nuts. The Dutch describe the roasted Macrozamia nuts ‘as tasting like Dutch broad beans, or, when less ripe [sic.], like hazelnuts’ (Playford 1998: 36) or as Seddon (2005: 67) interprets it ‘when ripe, like hazelnuts.’ Given that the Macrozamia fruiting season is approximately mid-February to mid-April, there would not have been ripe red fruit available at the time of the Dutch exploration of the Swan River region.

The Baudin Expedition – the French Lieutenant Commander Milius at the Swan River

The French Lieutenant Commander Milius whose party explored the shores of the Swan River in June 1801 (as part of the Baudin expedition) also became seriously ill “vomiting blood” after consuming

‘nuts like chestnuts which the naturalist and sailors roasted and ate with relish, commenting that these tasted like European chestnuts’ (Marchant 1998: 169).

These “nuts” would have been de-fleshed Macrozamia seeds similar to those pictured in Plate 9 that had been discarded or left over from an earlier fruiting season.

The Flinders Expedition – Esperance region

On January 10th 1802 the Scottish botanist Robert Brown who accompanied Matthew Flinders aboard the Investigator visiting the south coast of Western Australia, records how he consumed 16 nuts of Zamia without any ill-effects.6 However, he points out that other members of the crew were not so lucky. They suffered the punishing effects of cycad nut poisoning:

“sickness & retching [and] headache. In some the sickness came on [after] about an hour or two. In others it did not intervene for several hours. Mr Bauer felt only a Rise of Curd at his stomach all day but about 10 at night he was attacked with sickness which lasted till 2 in the morning.’ (Short 2002: 15-16)

Is it a coincidence that Brown acknowledges in his diary that he happened to be reading Henry’s Epitome of Chemistry and Cook’s Third Voyage at the same time as he extravagantly boasts of his capacity to ingest numerous cycad nuts without any adverse effect? Being a renown botanist he would have been familiar with the reference to Cook’s crew having suffered severely from cycad poisoning when visiting northeastern Australia in 1770.7

George Grey’s party in the vicinity of the Gairdner Range

What is the probability that almost forty years later the young explorer George Grey (1841:295-6) should also be reading Cook’s Voyage (Vol 2, page 624) and quoting from it around the time when his own men (like those of Cook, Milius and Brown) suffered violent bouts of sickness after consuming a store of Macrozamia nuts which they had found at an Aboriginal camp, somewhere in the vicinity of the Gairdner Range in the Dandaragan region, north of Perth.

‘13th April 1839 – Kaiber here brought in some of the nuts of the Zamia tree; they were dry, and, therefore, in a fit state to eat. I accordingly shared them amongst the party. Several of the men then straggled off to look for more, and were imprudent enough, before I found out what they were doing, to eat several of the nuts which were not sufficiently dried, the consequences of which were, that they were seized with violent fits of vomiting, accompanied by vertigo, and other distressing symptoms; these, however, gradually abated during the night, and in the morning, although rendered more weak than they were before, the poor fellows were still able to resume their march.’ (Grey 1841: 61)

After suffering such traumatic consequences from eating what we suspect were either toxic Macrozamia kernels or rancid sarcotesta or simply over-indulging on this rich oily food, it is scarcely credible that the following day these same hungry and weakened men repeated the experiment of consuming Zamia nuts, this time without any reported ill-effects. Did Grey advise his men only to eat the processed sarcotesta and not the kernel, this second time round? Or was Grey trying to illustrate to his readers how dangerous this exotic food source was to the unsuspecting hungry settler or explorer? One of us wonders if this critical incident actually happened to Grey’s men or was it nothing more than a dramatic device to entertain his readers?

In his journal Grey (1841) quotes from Cook’s Voyage describing the cycad poisoning incident which involved a Cycas species (possibly Cycas media) – the nuts were:

‘…about the size of a large chestnut, but rounder. As the hulls of these were found scattered round the places where the Indians [Aborigines] had made their fires, it was taken for granted that they were fit to eat; however, those who made the experiment paid dear for their knowledge to the contrary, for they operated both as an emetic and cathartic, with great violence…(Grey 1841, Vol 2: 295 quoting from Captain Cook’s first voyage).

It is probable, however, that the poisonous quality of these nuts may lie in the juice, like that of the cassada [cassava] of the West Indies, and that the pulp, when dried, may be not only wholesome but nutritious.’ (Grey 1841, Vol 2: 296 quoting from Captain Cook’s first voyage).

We speculate that the substance of this extract from Captain Cook’s Voyage (originally recorded by Joseph Banks) was to shape Grey’s views on the fundamental reason for the Noongar processing of Macrozamia sarcotesta in southwestern Australia and that soaking and burying the Macrozamia nut was believed to rid the “pulp” of its toxic qualities and that the resulting dryness of the sarcotesta was considered the final hallmark of safety, thereby rendering it “nutritious” and edible.

Grey (1841: 296) categorically states that Macrozamia nuts were buried and

‘in about a fortnight the pulp which encases the nut becomes quite dry, and it is then fit to eat, but if eaten before that it produces the effects already described.’

It is not surprising that Grey adopts the same words “emetic and cathartic” as those used in Captain Cook’s journal to describe the harmful consequences of eating unprocessed pulp. He writes:

‘No article of food used by the natives is more deserving of notice than the by-yu. This name is applied to the pulp of the nut of a species of palm, which, in its natural state, acts as a most violent emetic and cathartic; the natives themselves consider it as a rank poison: they, however, are acquainted with a very artificial method of preparing it, by which it is completely deprived of its noxious qualities, and then becomes an agreeable and nutritious article of food.’

However, Grey (1841: 297) points out that traditional Noongar processing did not diminish the toxins contained in the kernel:

‘The process which these nuts undergo in the hands of the natives has no effect upon the kernel, which still acts both as a strong emetic and cathartic. ’ (Grey 1841: 297)

Noongar names for the Macrozamia kernel

Noongar names recorded by Grey (1840) and Moore (1842) for the Macrozamia kernel include dyundo, wida and gargoin. The etiology of these terms is unclear but we would suggest that d-yundo is a body part metaphor referring to the de-fleshed or “bald” nut (that is, without its edible red covering). Grey (1840: 34) translates dyundo as meaning bald.8

Bussell (n.d.) records buoyer queaja as the name for Zamia nuts. This is possibly another body part metaphor signifying ‘flesh and bone’ (buoyer meaning flesh/fat and queaja/ kweitch, referring to bone). With ageing and weathering the Macrozamia seeds lying around on the white/grey sandy soils of the Swan Coastal plain become bone-coloured as depicted below.

Ethnohistorical descriptions of how and why bayoo fruit was processed

There are numerous accounts of European explorers (e.g. members of Vlamingh’s crew 1697, Lieutenant Commander Milius’s crew 1801 who formed part of the Baudin expedition, Matthew Flinders’ party 1802, Captain Fremantle’s party 1829 and Lieutenant George Grey’s men 1839) all having suffered the ill-effects of cycad nut consumption in southwestern Australia. The accounts are often vague and difficult to interpret, although the nuts were generally found in the vicinity of Aboriginal camp sites, so it was assumed that the local indigenous inhabitants must have eaten them. The chestnut-resembling size and appearance of de-fleshed Macrozamia nuts would have been too great a temptation to the hungry, unsuspecting European explorer. In most cases they were consuming the whole nut (including the kernel) not just the sarcotesta. There was a deeply entrenched colonial belief (promoted by Moore 1835 and Grey 1840, 1841) that the sarcotesta required detoxification through indigenous processing before it was edible. This assumption about ripe Macrozamia sarcotesta being toxic to humans unless having undergone extensive indigenous processing is still held to this day (see Meagher 1974; Smith 1982, 1992, 1999; Bindon 1996:173 and Asmussen 2011, 2012).

In this paper we do not question the toxicity of the de-fleshed Macrozamia seed (or “nut” as it is often called) for this has been scientifically well-established to contain harmful substances in particular cycasin and macrozamin and it is well known that Aboriginal people in Eastern Australia always carefully processed the seeds using methods such as water-leaching, ageing and roasting prior to consuming the starchy kernel or endosperm.

What we question is the view that has been promoted since the early colonial period (e.g. Grey 1840 and Moore 1842) and continues to this day in the archaeological, ethnobotanical and ethnographic literature that Noongar people processed the sarcotesta primarily for detoxification purposes. However, not all the early recorders mention sarcotesta toxicity as the reason for indigenous processing as the following review of the early literature shows.

As early as 1831 George Fletcher Moore writes:

‘The Zamia produces a sort of nut which the natives eat after considerable preparation by steeping in water but without this process it is said to be poisonous….’ (Moore 1831 in Cameron 2006: 14)

A few years later Moore (1835) describes eating some prepared baio after it had been processed:

‘Gigat invited us to eat some “Baio” along with him. The fruit, which is esteemed by them as a great delicacy, is the red skinned nut which is contained in the Fruit cone of the “Zamia.” The fleshy skin, for it scarcely can be called pulp, is the only part which is edible & even this is considered poisonous until it has been steeped so long in water, or buried in the earth, as to arrive at a state approaching decay. The flavor is something like that of medlar, or the taste of old cheese. Some of our party appeared to relish it but afterwards complained of its effects.’ (Moore 14th April 1835 in Schoobert 2005: 424)

We would suggest that Moore’s men were not suffering from cycad seed poisoning but rather their gut microbiome was ill-adapted to digest this rich fatty (and to them) alien food.

Moore’s original spelling of baio (1835) changes to by-yu (1842) in agreement with George Grey’s spelling:

‘by-yu – The fruit of the zamia tree. This in its natural state is poisonous; but the natives, who are very fond of it, deprive it of its injurious qualities by soaking it in water for a few days, and then burying it in sand, where it is left until it is nearly dry, and is then fit to eat. They usually roast it, when it possesses a flavour not unlike a mealy chestnut; it is in full season in the month of May. It is almost the only thing at all approaching to a fruit which the country produces.’ (Moore 1842:24).

Grey (1841) in his description of by-yu emphasises that:

Europeans who are not acquainted with this mode of preparing the nut, the stones of which they find lying about the fireplaces of the natives, are frequently tempted to eat it in its natural state, but they invariably pay a severe penalty for the mistake.’ (Grey 1841: 295)

-

Button

Plate 15: Cross-section of a ripe unprocessed bayoo fruit. The red seed covering was consumed only after soaking and/or burying. Grey (1841) refers to the sarcotesta as “pulp” whereas Moore (1835) says the “fleshy skin” can hardly be called “pulp.” Backhouse (1843) and Drummond (1862: 28) refer to it as “rind.” Photo by Ken Macintyre 2009

-

Button

Plate 16: Cross section showing the oily processed sarcotesta enveloping the starchy endosperm or seed. The orange stain on the seed is carotene-enriched oil from the sarcotesta. Photo by Ken Macintyre 2009.

-

Button

Plate 17: James Drummond, the first colonial botanist (Wikipedia)

Salvado (1851 in Stormon 1977: 161) describes the Zamia nut or poio as having “no pulp” and comments:

‘The shell is red, and of fine texture, with no pulp. In order to make them fit for eating, the natives bury the flower [cone] together with the nuts for a certain time a couple of feet deep in the ground. The heat of the earth makes them swell as if to germinate a new plant, and they are then cooked on hot coals to form a substantial food with a pleasant taste.’

Salvado (1851 in Stormon 1977: 213) describes the sarcotesta of Macrozamia fraseri (or what he refers to as Encephalartos spiralis) as becoming “pulpy” after processing:

‘the very thin scarlet shell, which becomes pulpy only when properly treated for eating’ (Salvado 1851 in Stormon 1977: 213).

Our own experiments demonstrated that the sarcotesta increases its pulpiness after processing.

Drummond (1839) refers to the “red-coloured arillus” as a favourite food of the natives.’ He writes:

‘…the fruit of the female palm is like a large pineapple. It contains many nuts about an inch long, covered with a red coloured arillus, which is a favourite food of the natives. To prepare the nuts and arillus for use, they steep them in water or bury them in the earth for some weeks, where they undergo a sort of fermentation and become wholesome food; when eaten without this preparation, they produce violent vomiting and other dangerous symptoms.’ (June 1839, in his Letter to Sir William Jackson Hooker, see p.18)

In 1842 Drummond observed that the large female “Zamia” cones:

‘contain numerous nuts, larger than a chestnut, and when ripe, they are covered with a beautiful red covering generally about two lines thick; this covering is a favourite food of the natives – they call the nuts “boyas.” Before they use the red covering of the nuts as food, they bury them in the ground for several weeks, or steep them in water, which has the same effect in a shorter time; when eaten without that preparation, they cause violent vomiting, and other distressing symptoms. The nuts, when deprived of their red covering, are not used by the natives as food (Drummond 1842 Letter No. 8, 28th September 1842).

Moore (1835), Drummond (1839) and Grey (1841, Vol 2: 296-297) all assume that indigenous processing of the Zamia nut took place to detoxify the pulp:

‘The native women collect the nuts from the palms [Macrozamia] in the month of March, and having placed them in some shallow pool of water, they leave them to soak for several days. When they have ascertained that the by-yu has been immersed in water for a sufficient time, they dig, in a dry sandy place, holes which they call mor-dak; these holes are about the depth that a person’s arms can reach, and one foot in diameter; they line them with rushes, and fill them up with the nuts, over which they sprinkle a little sand, and then cover the holes nicely over with the tops of the grass-tree; in about a fortnight the pulp which encases the nut becomes quite dry, and it is then fit to eat, but if eaten before that it produces the effects already described. The natives eat this pulp both raw [that is, processed but not roasted] and roasted; in the latter state they taste quite as well as a chestnut.’ (Grey 1841, Vol 2: 296)

Moore (1835) refers to the ‘fleshy skin’ as poisonous and Grey (1841: 295) states that the Aborigines themselves considered the pulp of the nut as ‘a rank poison.’ However, when Grey tried to inquire as to their reasons for processing it and the origin of this tradition, he could not get an answer that satisfied him. He states:

‘I have taken some trouble to ascertain if any traditional notion exists amongst the natives, which would in any way account for their having first obtained a knowledge of the means by which they could render the deleterious pulp of the Zamia nut a useful article of food; but in this, as in all other similar instances, they are very unwilling to confess their ignorance of a thing, and rather than do so, will often invent a tradition.’

It would seem that Grey did not understand their cultural explanation for why the by-yu was fermented. We would suspect that their explanation involved mythological metaphor rather than a scientific explanation that Grey was seeking. His view about the pulp being highly toxic and injurious to health may have derived from the experience of his own men and earlier explorer accounts combined with the popular colonial hearsay of the time. Perhaps his indigenous informants were not providing him with the information that he wanted to hear. Could we assume that his informants were providing him with an explanation that did not relate in any way to the extraction of toxins? It would seem that Grey (1841) trivialises what they are telling him, by pointing out to his readers ‘Hence many intelligent persons have raised most absurd theories, and have committed lamentable errors.’ In retrospect does Grey’s comment reflect on his own assumptions? We think that Grey’s informants may have been trying to explain to him that by-yu fermentation improved its taste and food value.

Bunbury (1836) and Backhouse (1843) do not mention toxicity at all in their accounts of bayoo processing

We find it surprising that Bunbury (1836) and Backhouse (1843) who would have been well-acquainted with the colonial comment of the time about the toxicity of this indigenous food without proper processing, do not mention detoxification as a reason for processing the sarcotesta prior to its ingestion.

Bunbury (1836) compares the two methods of indigenous processing and states:

‘The quickest method of ripening the Bayoo nuts is to bury them in a hole of water at the edge of a swamp or river when they become fit to eat in a few days but in this way they acquire a very strong bad smell & unpleasant taste, so I recommend all who are willing to wait a month for such delicacies, to bury them in the dry ground rather than in water.’ (Bunbury 1836 in Cameron and Barnes 2014:136)

Backhouse (1843) does not mention detoxification as a reason for processing Macrozamia sarcotesta but states with reference to the Perth area that:

‘…the Natives bury, or macerate, the nuts, till the rinds become half decomposed, in which state they eat the rind, rejecting the kernel; but in N.S.W., they pound and macerate the kernels, and then roast and eat, the rough paste.’ (1843:542).

Is Macrozamia sarcotesta toxic?

There are contradictions in the literature regarding the question of whether the sarcotesta of Macrozamia is toxic or not.9 Ladd (1993) in a one-off obscure study states that the sarcotesta of Macrozamia riedlei is ten times more toxic than the endosperm – a view that totally contradicts a 1938 study by the WA Government Chemical laboratories which showed the endosperm or kernel of Macrozamia fraseri to be highly toxic but the sarcotesta to be non-toxic.

We have long been confounded by Ladd’s (1993) results which not only contradict the WA Government Chemical laboratory findings but also defy cultural logic. Why would Noongar people eat the sarcotesta if it was so highly toxic and then discard the starchy kernel which according to Ladd’s study is less toxic? Asmussen (2011) seems to have accepted Ladd’s findings without question and formulates her discussion of Noongar processing on this premise. In doing this she further endorses the idea promoted by the early colonial writers, such as Grey (1840) and Moore (1842), that the sarcotesta of Macrozamia was processed by Noongar people for detoxification purposes. Asmussen states with reference to Ladd’s study:

‘Ladd et al.’s (1993: 39) research on the poisonous macrozamin content of a range of cycad species indicates that the Noongar people utilized the most toxic part of M. riedlei seeds, and discarded the least toxic part. The sarcotesta of M. riedlei contains a relatively high amount of macrozamin at 3.88% of fresh weight, comparable to that found in the kernels of M. miquelii and M. moorei (F. Muell)….’ (Asmussen 2011: 153).

Asmussen (2011) asks the same question that we have long puzzled over and asked ourselves, ever since reading Ladd’s study results:’

‘Why detoxify and consume the sarcotesta, which is the most toxic part of the resource?’ (Asmussen 2011:153)

If indeed the sarcotesta of Macrozamia reidlei is ten times more toxic than the endosperm, why has the ChemCentre WA not updated their records?

The ChemCentre was not aware of Macrozamia sarcotesta being toxic when we first asked them about it in 2008. In our own privately funded experiments we fed two white rats a diet of raw Macrozamia sarcotesta mixed with banana over a ten day period. Our results, like those of the Government Chemical Laboratories in 1938 which tested raw sarcotesta on guinea pigs, showed no adverse results. If anything our white rats thrived on this diet and looked very healthy. See our paper detailing the results of tests conducted by the Chem Centre WA on the nutritional value of the sarcotesta before and processing here.

This is the first time that processed Macrozamia sarcotesta has been chemically tested for its food value. Previous testing of Macrozamia sarcotesta that was carried out in 1938 and 1939 by the Chemical Branch of the Mines Department assessed the food value of unprocessed sarcotesta. These tests determined that only the seeds were poisonous.

Cycad seed sarcotesta toxicity has been much debated in the literature.10 A compelling study by Hall and Walter (2014) which chemically tested the sarcotesta of Macrozamia miquelii from Eastern Australia found it to be non-toxic. They found no cycasin present in the “brightly coloured fleshy “fruit” of sarcotesta” and they proposed that the non-toxic Macrozamia sarcotesta was probably an ancient adaptation that served as ‘a reward for cycad seed dispersal fauna’ (2014: 860).

We believe that the bright red sarcotesta of Macrozamia fruit from southwestern Australia when ripe is also non-toxic and similarly functions as a “reward” for bird and animal seed dispersers. Why would a plant poison its own seed dispersal agents on which it relies for survival?

Hall and Walter (2013) write:

Globally, cycads are characterized by large, heavy seeds with an outermost fleshy layer (the sarcotesta) that on ripening develops vibrant colors…. Cycad seeds contain unique toxic compounds such as cycasin and macrozamin … However, the sarcotesta layer appears to be free of these poisonous compounds (Hall, 2011).’ (Walter and Hall 2013: 1127)

Hall and Walter’s (2014) further analysis of the ripe sarcotesta of cycads from Eastern Australia, including Macrozamia miquelii, showed that

“There is Toxic Cycasin in the Seeds of Cycads, but Not Their Sarcotesta “Fruit” ‘(Hall and Walter 2014: 862)

This is consistent with the findings of the Chemical Branch of the Mines Department (1938-1939) which, as already noted above, found that only the seeds of Macrozamia fraseri were poisonous.

Burbidge and Whelan (1982: 66) from animal studies and personal communication with J.R. Cannon support the idea that the sarcotesta of Macrozamia riedlei is non-toxic. They note that:

‘In Macrozamia seeds, the poison is confined to inside the stony layer (J. R. Cannon, pers. comm.)

Ripeness of the bayoo fruit

It is our contention that the sarcotesta of Macrozamia species from southwestern Australian (M. fraseri, M. reidlei and M. dyeri) is non-toxic at the time of full physiological ripeness when the seeds are bright red coloured, dehiscing from the female cone and releasing a distinctive odour. Prior to this stage it is highly possible that the unripe sarcotesta contains toxins as part of the seed’s chemical armoury against herbivore predators, pests and pathogens. When the cone starts to disintegrate and the seeds are exposed to natural elements of the external environment, such as sunlight (and possibly other factors such as moisture and humidity) we maintain that any toxins, if present, are reduced or eliminated. From our own observations sunlight appears to be an essential ingredient in the ripening process.

We cannot emphasise enough the importance of physiological ripeness when it comes to harvesting Noongar plant foods, most especially the bayoo. During the Macrozamia seeding season Noongar people were constantly aware of the different birds and animals that were drawn into the ecological food chain of predation on the ripening fruit. These were viewed as indicators that the fruit was ripe and ready for collecting and processing. The traditional Noongar could easily locate patches of ripening bayoo from a distance by the sight of hovering or circling birds of prey, such as the brown hawk (kargyne) or whistling kite (jandoo). These iconic avian predators were attracted to a rich food chain of smaller birds, reptiles, insects and marsupials that were magnetically attracted to the ripe Macrozamia fruit by its odour and bright red colour. Humans too were part of this complex food chain.

We are writing a paper soon to be uploaded to this website on the use by Noongar people of birds and animals as ecological indicators of Macrozamia fruit ripeness – signifying the readiness of this important seasonal resource for human harvest and processing.

-

Button

Plate 19: Whistling kite or jandoo: “The commonest large hawk in Western Australia” (Serventy and Whittell 1976: 163). These hawks served as ecological indicators of Macrozamia fruit ripeness and could be seen from a distance hovering above the Macrozamia “groves” attracted to the presence of insects, smaller birds and reptiles congregating there. Photo by Matthew Dwyer https://www.facebook.com/MatthewDwyerPhotography/

-

Button

Plate 20: These scarlet coloured bayoo looked ripe at the time of taking the photograph but lacked the distinctive pungent odour signifying ripeness and attracting seed-dispersal agents. Photo by Barb Dobson 2009

-

Button

Plate 21: These bayoo are ripe and ready for processing. Photo by Barb Dobson

-

Button

Plate 22: These over-ripe bayoo fruit had a strong odour but showed signs of decay and animal predation. Over-ripe Macrozamia fruit decays rapidly. Photo by Barb Dobson.

-

Button

Plate 23: Insects, birds and animals that predate on the ripe sarcotesta often leave behind a trail of cleaned seeds or partially cleaned seeds under or in proximity to the female plant. This seed was partially cleaned of its sarcotesta by an unidentified bird or animal at Bold Park bushland. Photo by Barb Dobson.

-

Button

Plate 24: A shallow fermentation pit experiment that we conducted in 2009 demonstrates insect predation on the by-yu fruit after two weeks burial. Photo by Ken Macintyre 2009.

Archaeological Evidence of Macrozamia pits

The earliest archaeological evidence of indigenous Macrozamia seed sarcotesta pit processing in Australia derives from southwestern Australia where Smith (1982) located ancient Macrozamia kernels in association with Xanthorrhoea leaf bases in a shallow 20cm deep pit that she suggests may have been used for water-leaching or fermentation purposes. This ancient evidence of Macrozamia pit processing at Cheetup Rockshelter in the Esperance region which dates back approximately 13,000 years BP during the late Pleistocene (Smith 1982, 1996, 1999) predates by about 9000 years the earliest archaeological records for cycad seed processing in Northern and Eastern Australia.10

Fermentation or leaching of Macrozamia fruit may have occurred within a shallow lined pit; however, based on our own reconstructive processing experiments, we found that shallow pits attracted predation from insects (such as weevils) and domestic rats. We would suggest that the deeper pits – about an “arm’s length” depth as recorded by Grey (1840, 1841) – would have afforded a number of advantages including a constant anaerobic and thermogenic environment for fermentation to occur as well as affording protection against insect and small burrowing-animal predation. We would suggest that when Grey (1840, 1841) records the depth (mordak) as an “arm’s length,” he is referring to a woman’s arm length (possibly about 50-60cm) for women were responsible for digging using their wannas. Depth of pit was important to protect the fermenting fruit from human and non-human predators. The soil digging habits of the kwenda (short nosed bandicoot) – which according to some Elders we consulted is a sarcotesta eater – may explain why fermentation pits were deep – to prevent the valuable stores of fat-rich food from being raided by digging marsupials.

Ownership rights over by-yu fruit

We are told that Grey’s indigenous guide Kaiber discovered four “holes” of stored Zamia nuts known as by-yu and that he came to request ‘permission’ from Grey ‘to steal them’ (1841, Vol 2: 64). Grey translates Kaiber’s comments as follows:

’14th April – If we take all, this people will be angered greatly; they will say, ‘What thief has stolen here: track his footsteps, spear him through the heart; wherefore has he stolen our hidden food?’ But is we take what is buried in one hole, they will say – ‘Hungry people have been here; they were very empty, and now their bellies are full; they may be sorcerers; now they will not eat us as we sleep’ (Grey 1841, Vol 2: 64-65).

‘Good- it is good Kaiber,” I replied; “come with me, and we will rob one hole;” and accordingly we went and took the contents of one, leaving three others undisturbed. I brought back these nuts to the men, and we shared them amongst us.’ (Grey 1841, Vol 2: 65).

Grey (1840: 48), referring to the King George Sound area, records gwin-een as ‘the common stock of food.’

The name quinene or quinine was first recorded for this food in 1830 by Captain Collet Barker who was told by his Aboriginal guide and informant Mokare that:

‘the provision of Quinene is made by everyone, but is often stolen. Generally speaking the owners are not sulky at this, it not being considered so sacred a property as Spears, Kangaroo, Wallabi,etc, or even grass trees, but he recollects hearing of one man speared on account of it.’

Bunbury (1836 in Cameron 2014:136), when exploring the Perth to Pinjarra region, refers to the bayoo:

‘The Zamia plants are considered private property by the natives who do not consider it right to gather Bayoo belonging to others, though they do not scruple to catch and eat any animals, birds or reptiles, they may meet with in their passage through the lands or buggia [i.e. boodjor, land, country] of other tribes. ‘

What Bunbury did not realise when making these statements was that he was demonstrating the difference between certain carefully managed bio-cultural resources (such as the Zamia, grass tree, kangaroo and wallabi) whereas the others were a composite of common property.

The quinine trade

Ethel Hassell, who was recording her observations of Aboriginal culture in the 1880’s at Jerramongup, refers to the trading of processed Macrozamia sarcotesta known as quinine from the coast to inland areas where the Macrozamia did not grow. She gives little detail on the trading relationship that took place, other than a description of how the quinine was prepared. She comments that:

‘For trading, the natives take the stone out, which are never eaten, as they retain the poison, and string the fruit on rushes. They never lose their red colour or shiny look, and keep good for quite a long time (Hassell 1974: 25).

Stringing the fruit on rushes would have facilitated portability, preservation and storage of this much coveted food. With our own reconstructive experiments we found that the processed and preserved sarcotesta fruit retained its colour, odour and most of its food value after being kept for 12 months in a dry, airtight environment (see photo below). Tests conducted by the ChemCentre WA verified its high food value after 12 months. See forthcoming paper soon to be uploaded to this website.

It is a pity that Hassell does not provide any further details on this unique trade and we wonder if it only occurred in the southern region? Also, what did the inland Wheelman people provide in exchange for this relished comestible from the coast? What were the trading relationships between these groups and how was this surplus of Macrozamia sarcotesta obtained? Was there some form of active cultivation taking place? Did this preserved oily fruit have a ritual value?

The taste of processed bayoo

We could find no agreement in the ethnohistorical literature on the taste of the fermented sarcotesta of Macrozamia. Whether this was due to a reluctance to taste it for fear of its toxicity or its unfamiliar and unappetising appeal to the Western palate is unclear. In 1835 Moore describes the flavour as:

‘something like that of medlar, or the taste of old cheese. Some of our party appeared to relish it but afterwards complained of its effects.’ (Moore 1835 in Schoobert 2005: 424)

At a later date Moore (1842: 23-24) describes the taste after being roasted as having ‘a flavour not unlike a mealy chestnut.’ This somewhat mirrors Grey’s description in his exploration journal (1841, Vol.2: 296) a year earlier where he comments that it tastes after roasting ‘quite as well as a chestnut.’ (Grey 1841, Vol 2: 296).

Bunbury (1836: 136) does not comment on taste, except to point out that the underground fermented bayoo have a much better taste than those soaked in water for only ‘a few days’ for the latter ‘acquire a very strong bad smell & unpleasant taste.’

Salvado (1851 in Stormon 1977: 161) describes poio as “pleasant” tasting:

‘…they are then cooked on hot coals to form a substantial food with a pleasant taste.’

Drummond (1862: 28), on the other hand, states:

‘To me it was disgusting, the taste being rancid, and resembling train oil’

Hammond (1933:28) describes boyoo after soaking in salt water as resembling ‘a tomato in colour and taste.’

Hassell (1975: 25) describes the taste and texture of quinine after being buried for a prolonged period as

‘soft and resembles a date but tastes very like an olive.’

Lyon (1833 in Green 1979: 168) describes a tasty treat in the form of a zamia fruit and frog cake. He states:

‘When the men return to the camp at night they are presented each with a cake by the women, apparently made of the fruit of the zamia and the flesh of frogs.‘

We suspect this cake was an oily mixture of the treated fruit of zamia squeezed together using the tips of the fingers with cooked frog meat.

The processed sarcotesta was either eaten raw or roasted. However, based on our own experience one has to be careful when cooking the sarcotesta not to lose the valuable oil. When one of us (Ken Macintyre) tasted processed (but unroasted) sarcotesta, he said:

It was a very rich and oily taste experience. It had the aroma of over-ripe Macrozamia fruit and the oily taste coated my palate after swallowing. It was not unlike my first experience tasting olive oil. To the Western palate Macrozamia sarcotesta would in my opinion be an acquired taste.’ (Ken Macintyre 2011).

Roasted Macrozamia sarcotesta

“Oiliness’ best describes the taste and texture of treated Macrozamia sarcotesta (Macintyre 2011)

In an early experiment in 2008 we prepared the sarcotesta, after it had been soaked and buried, by cutting it into strips and cooking it for about seven minutes on a hot barbecue plate. The sarcotesta sizzled and released a considerable quantity of oil. The taste and texture of cooked sarcotesta was difficult to describe.

It had a mild salty/sweetish taste somewhat resembling rice bran oil. I found it difficult to compare to any other food item that I was familiar with’ (Macintyre 2011).

We imagine that the early recorders may have encountered similar difficulties in describing this unfamiliar taste experience. Culturally novel taste sensations of fat-rich sarcotesta may possibly be explained by a newly discovered taste – a sixth basic taste – known as the “fat taste” or “oleogustus” (Latin, oleo, oily or fatty +gustus, taste). This new taste was recently identified by a team of American scientists in 2015 ‘to refer specifically to the chemistry of taste rather than a textural connotation’ (Running et al 2015: 515). Could “oleogustus” convey the range of gustatory sensations associated with processed Macrozamia sarcotesta?

Foods rich in fat will often absorb pungent esters during the fermentation process which add to their flavour and attractiveness to the human palate, like in the case of a matured stilton cheese. We would suggest that fermented bayoo underwent a similar transformation and that its resultant taste was culturally relished and sought-after as well as being highly nutritious.

Grey (1840:16) refers to April and May as ‘the season for eating by-yu’ or “By-yu ngannoween.” Moore (1842) records the name of the April-May season as geran (nowadays know as “jeran”). This term translates as “fat” (jerang, jerrung, cherung) and corresponds to the time of the year around autumn when it was mandatory for Noongar people to build up their reserves of sub-cutaneous body fat to ensure their survival through the long cold dark wet lean season of makuru (known as mokkar or makur in the Albany region). A wide range of fat-rich foods were consumed at this time including bardi, kuya (frog), yakkan (turtle), kalda (mullet) and salmon.

Summary

It is not uncommon throughout the world for indigenous peoples to process and preserve food in different ways through soaking, salting, drying and fermenting to enhance the taste, texture and nutrient value of the food. Archaeological evidence suggests that the Noongar people of southwestern Australia practised a unique method of pit fermentation that increased the nutrient value of cycad sarcotesta at least 13,000 years ago during the late Pleistocene. This would have to be one of the earliest methods of food fermentation recorded in the world. The Noongar are the only documented group in Australia to have consumed Macrozamia sarcotesta after processing through anaerobic fermentation. In this paper we have questioned the observations and assumptions of Grey (1839), Moore (1842) and Drummond (1842) that the sarcotesta of Macrozamia seed was processed primarily to rid it of its toxic properties.

Grey’s (1842) wordlists and his often-quoted exploration journals profoundly influenced colonial hearsay and even to this day continue to provide a pivotal reference for researchers wishing to gain insights into aspects of traditional Noongar culture. However, we challenge his theory that the by-yu or Macrozamia ‘pulp” (thin fleshy outer layer) was processed by indigenous people primarily for the purpose of detoxification. Instead we argue that the ripe sarcotesta was processed to improve the taste, nutritional content and to facilitate its removal from the seed which was discarded. Soaking and/or anaerobic fermentation may have also played a part in extending the seasonal shelf life of the fruit which in some parts of the country was used as an article of trade.

Throughout this paper we have been frustrated by the lack of scientific analysis and/or updated records at the ChemCentre WA and relevant government departments concerning the question of the toxicity of the sarcotesta of local species of Macrozamia. As far as we are aware there have been no studies conducted since the Government Chemical Laboratory findings in 1938-1939 which determined the sarcotesta of Macrozamia fraseri to be non-toxic. There has only been one little-known study by Ladd et al (1993) which contradicts the earlier findings of the WA Government Chemical Laboratory. Ladd’s paper which highlights the toxicity of Macrozamia sarcotesta was prepared as a conference paper and to our knowledge has not been followed up with any replicative studies or further publications which consolidate his initial findings. We do not understand why such a supposedly dangerous and toxic neuro-chemical such as macrozamin has not been thoroughly studied in the sarcotesta of the commonly occurring fruit/seed of local species of Macrozamia found in our urban parklands and bushlands.

We would strongly recommend that further research and chemical analysis be carried out using ripe sarcotesta of local Macrozamia to establish once and for all whether this red outer layer of the seed when fully ripe is harmful to humans.

We caution readers not to experiment with consuming any part of the Macrozamia seed or sarcotesta for safety purposes. The seed is well known to contain toxins while the toxicity of the sarcotesta when fully ripe is yet to be definitively assessed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge and thank all the Noongar Elders who have assisted us over the years by providing anecdotal and cultural information on the history, preparation and usage of their traditional foods and medicines.

Our interpretations of the ethnohistorical sources may be inconsistent with the views of some contemporary Noongar people.

ANNOTATIONS

1. We are not questioning here the toxicity of the Macrozamiaseed kernel for this has been well-established in the scientific literature. Noongar people did not eat the kernel even after processing. The kernel is well- known to contain harmful substances, especially macrozamin a toxic glycoside (or MAM glycoside) first isolated from the kernel of Macrozamia spiralis in 1940 and from the kernel of M. riedlei by Lythgoe and Riggs in 1949. It is historically well-established that Macrozamia seeds and leaves contain toxins harmful to cattle and sheep causing “zamia staggers” or “wobbles” (that is, partial paralysis of their hind legs) together with other debilitating symptoms. It is for this reason that Macrozamia plants were extensively “grubbed out” (removed) by pastoralists and farmers to avoid damage to their livestock.

Our question is whether the sarcotesta when fully ripe is toxic or not? If it is chemically analysed and found not to contain toxins, nhen we can conclude that Noongar processing was NOT for detoxification purposes, despite the common view in the literature that it was processed to remove toxins to make it edible. It is our view that the sarcotesta was probably not toxic at the time of indigenous harvest when the seed was fully ripe, when it was emitting a distinctive odour and starting to be dispersed by animal and bird seed vectors. It is our argument in this paper that traditional sarcotesta processing and preparation was to improve its palatability, nutritional value, pulpiness and digestibility as well as providing an effective means of hidden storage and repository of a valued food away from predators.

2. Aboriginal groups in Eastern Australia detoxified the kernel using a variety of means including ageing, water-leaching and roasting but did not use anaerobic pit fermentation.

3. It is probable that unripe Macrozamia sarcotesta may contain toxins as part of the seed’s chemical defence against predators, pests and pathogens.

4. Botanist and naturalist Baron Charles von Huegel first set foot on the sandy soil at the mouth of the Swan River on 27thNovember 1833. He had arrived in the colony aboard the British naval frigate, the Alligator, which was anchored offshore Fremantle 27th Nov until 19th December when it set sail to King George Sound.

5. According to Osborne (2012)

‘Seeds of a local cycad (M. fraseri or M. reidlei) were taken back to Holland and presented to the mayor of Amsterdam, Nicolaas Witsen, but their subsequent fate is unknown (Forster 2004, Osborne 2006).’

6. It is unclear why Brown did not experience any adverse effects from eating such a large number of nuts, supposedly these were aged ones (10-11 months) which had lost much of their toxicity. Could it have been Brown’s daily heavy consumption of alcohol, a pint (568 mls) of port or ‘cherry’ whisky every night that protected him or was he simply exaggerating and boasting the number of nuts that he was able to eat without ill effect, perhaps to impress how strong his constitution was and how weak those of his men who ate fewer nuts than he? Perhaps he didn’t eat as many nuts as he said he did, if he ate any at all.

It is interesting how in these early zamia poisoning accounts the leaders of the expeditions are rarely reported as getting sick (e.g. Vlamingh, Robert Brown and Grey). Accounts of cycad poisoning, including those reported by Vlamingh’s officers (1697), the French Lieutenant Commander Milius’s party at the Swan River in June 1802, and Captain Fremantle at the Swan River in 1829, and Robert Brown 1802 in the Esperance region and Lt. Grey 1839 during an expedition north of Perth involving Macrozamia “nut” consumption generally all portrayed the expedition leaders as being intelligent men who showed a greater awareness and vigilance, and in the case of Brown’s experience a stronger bodily constitution than their weaker underlings who succumbed to often violent and debilitating ill-consequences after consumed the toxic nuts. Robert Brown who accompanied Flinders to the south coast of Western Australia was probably observing M. dyeri (or possibly M. riedlei). He refers to it as Zamia Spiralis based on its resemblance to Zamia spiralis (now called Macrozamia spiralis) found only in Eastern Australia.

According to Charles Moore (1883: 115)

‘In Robert Brown’s Prodromius, one of the first and best works so far as it went on the plants of Australia, only one species is described, and that under the name of Zamia spiralis, giving as habitats for this plant the very distant places of Sydney and King George’s Sound in Western Australia.’

Charles Moore (1883: 115) further points out:

‘It is not at all surprising that these plants found growing so far apart should have been considered to be identical, as both are very similar in every respect, but they are now regarded as perfectly distinct species, the western plant being named Macrozamia Fraseri, Miq., and our eastern or Sydney plant is still called by the original specific designation of spiralis, an absurd specific name it must be confessed now that the remarkably spiral characteristics of other species have become so well known.’

7. It is interesting to note that Robert Brown who had been reading Joseph Banks’ account of Cook’s Voyage and who describes the cycad poisoning of Cook’s men (and hogs) was responsible for naming Cycas media – the very cycad believed to be responsible for poisoning Cook’s hungry men in 1770. Parker (2002: 18-20) states that Cycas media was named by Robert Brown from specimens collected on Calder Island, off Mackay, Queensland.

8. Grey 1840: 34 translates d-yundo as meaning bald, e.g. bald head, dyundo kattige).

9. Spencer (1990: 17) referring to cycads (Cycas) has stated that

‘…the fleshy seed cover is said to lack poisonous properties…’

Others have disputed this view stating that the toxins are most highly concentrated in the outermost layers of the cycad seed.

Some studies of Macrozamia sarcotesta toxicity mention using “fresh” seeds (e.g. Ladd et al 1993). However, whether these seeds were also “fully ripe” and ready for bird and animal dispersal is unclear. Contextual details regarding stage of seed maturity/ripeness, genus or species identification, fire history, geographic locality, soil chemistry or other potentially relevant variables which may help to explain study findings of sarcotesta toxicity – or absence of toxicity – are not always provided.

We would recommend that if future scientific testing of Macrozamia seed sarcotesta takes place to determine conclusively whether it is toxic or not, that these tests take place when the seed is fully ripened – the sarcotesta is bright red, emitting a distinctive odour –when the seeds are dehiscing from the cone ready for bird and animal seed dispersal. If such tests determine the sarcotesta to be toxic, it may then be useful to replicate traditional reconstructive processing to determine whether any residual toxicity remains after processing and it is important that Noongar people be involved.

The Noongar people are the only Aboriginal group in Australia who prepared and consumed processed Macrozamia sarcotesta.

There are documented examples of populations in other parts of the world such as Guam, Mexico, Africa, Madagascar and southern Japan eating the sarcotesta of cycads (e.g. Cycas, Encephalartos and Dioon) but none of these involved anaerobic pit processing which is unique to the traditional Noongar people of southwestern Australia. Harvey (1945: 191) provides the only reference that we could find to an Australian Aboriginal group (the Karawa tribes of the Borroloola district of the Northern Territory) eating the raw husk (sarcotesta) of a cycad nut after drying in the sun. She describes the nut of Cycas media as ’about the size of a quandong, with a husk which is edible raw, and is a good food.’*

And yet this appears to be the same Cycas species that was responsible for the violent sickness which afflicted Captain Cook’s men and killed two of their hogs when the hulls which were found lying around Aboriginal camps in the vicinity of the Endeavour River, north Queensland were consumed. The men had assumed them to be edible but suffered dire consequences. Cycas, however, is a different genus of cycad to Macrozamia.

10. The earliest archaeological records for cycad seed processing in Northern and Eastern Australia date back only to the recent Holocene period, approximately 4,300 years BP (Beaton 1982; Beck 1992).

BIBILOGRAPHY

Abbott, I. 1983 Aboriginal names for plant species in south-western Australia.Forests Department of Western Australia.Technical paper No. 5.

Akbar. E.; Yaakob, Z.;’ Kamarudin, S.K; Ismail, M. and J. Salimon 2009 ‘Characteristic and composition of Jatropha Curas Oil seed from Malaysia and its potential as biodiesel feedstock,’ European Journal of Scientific Research, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 396-403.

Annual Report of the Chemical Branch, Mines Department, for the year 1938

Annual Report of the Chemical Branch, Mines Department, for the year 1939

Armstrong, F., 1836 Manners and habits of the Aborigines of Western Australia. From information collected by Mr F. Armstrong, Interpreter. The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal, Saturday, 5th November: 793–794.

Asmussen, Brit, 2009 ‘Another burning question: hunter-gatherer exploitation of Macrozamia spp.’ Archaeology in Oceania 43:142–149.

Asmussen, Brit 2008 ‘Anything more than a picnic? Re-considering arguments for ceremonial Macrozamia use in mid-Holocene Australia.’ Archaeology in Oceania 43:142–149.

Asmussen, Brit 2011 “There is likewise a nut…”1 A comparative ethnobotany of Aboriginal processing methods and consumption of Australian Bowenia, Cycas, Lepidozamia and Macrozamia species. In J. Specht and R. Torrence 2011 Changing Perspectives in Australian Archaeology, Part X pp. 147 -161. Technical Reports of the Australian Museum.

Backhouse, J., 1843 A Narrative of a Visit to the Australian Colonies. London: Hamilton Adams and Co.

Baird, A.M. 1939 A contribution to the life history of Macrozamia riedlei. J. Roy. Soc. W. Australia 25: 153-169.

Barker, Collet 1830 Journal. Available on Microfilm at the Battye Library, CSO Records. Perth. Original copy held at the State Library of New South Wales.

Barrett, R. and E.P Tay 2005 Perth Plants: A field guide to the bushland and Coastal Flora of Kings Park and Bold Park. First edition.

Barrett, R. and E.P Tay 2016 Perth Plants: A field guide to the bushland and Coastal Flora of Kings Park and Bold Park. Second edition.

Bates, D. 1938 The Passing of the Aborigines: A Lifetime spent among the Natives of Australia. London: John Murray.

Bates D. 1966 The Passing of the Aborigines. Second Edition. Melbourne: William Heinemann Ltd.

Bates, D. 1985. The Native Tribes of Western Australia. Isobel White (Ed.) Canberra: National Library of Australia.

Bates, Daisy 1992 Aboriginal Perth: Bibbulmun Biographies and Legends. Peter J. Bridge (Ed.) Carlisle, Perth: Hesperian Press.

Battcock, M. and S. Azam-Ali 1998 ‘Fermented Fruits and Vegetables: a global perspective.’ FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin No. 134. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

Beaton, J., 1982 Fire and water: aspects of Aboriginal management of cycads. Archaeology in Oceania 17(1): 51–58.

Beck, W., 1992 Aboriginal preparation of Cycas seeds in Australia. Economic Botany 46: 133–147. New York: The New York Botanic Garden.

Berndt, R.M. 1974 Aboriginal Tribes of Australia. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Berndt, R. M. and Berndt, C. H. (Eds). 1980 Aborigines of the West: Their Past & Their Present. Perth: University of Western Australia Press.

Bindon, P. and R. Chadwick (eds.) 1992 A Nyoongar Wordlist from the South-West of Western Australia. WA Museum, Anthropology Department.

Bindon, P. 1996 Useful Bush Plants. Perth: Western Australian Museum

Bird, C.F.M. and Beeck, C. 1988. Traditional Plant Foods in the Southwest of Western Australia: The Evidence From Salvage Ethnography. In: Meehan, B. and Jones, R. (Eds.). Archaeology with Ethnography: An Australian Perspective. School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University: Canberra.

Bonta, M. A. & R. Osborne. 2007 Cycads in the vernacular – a compendium of local names. Proceedings of Cycad 2005, the 7th International Conference on Cycad Biology, Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden 97: 143–175.

Brady, the Very Reverend J. 1845 A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Native Language of Western Australia. Rome: S.C. de Propaganda Fide. Typed Transcript at the Battye Library.

Brenner, E.D., Stevenson, D.W. and R.W. Twigg 2003 ‘Cycads: evolutionary innovations and the role of plant-derived neurotoxins.’ TRENDS in Plant Science, Vol 8. No. 9. September.

Brough Smyth, R., 1878. The Aborigines of Victoria. Melbourne: Victorian Government Printer.

Buller-Murphy, D. 1959. An Attempt to Eat the Moon. Melbourne: Georgian House: Melbourne.

Bunbury, W. St. P. and Morrell, W.P. (eds.) 1930 Early days in Western Australia, being the letters and journal of Lieut. H.W. Bunbury, 21st Fusiliers. London: Oxford University Press.

Bunbury, H.W. 1930 ‘Early Days in Western Australia.’ London: Oxford University Press. Journal entries for 1836.

Bunbury, H.W. 1836 Journal (see Bunbury and Morrell 1930)

Burbidge, A.H., & R.J. Whelan, 1982. Seed dispersal in a cycad, Macrozamia riedlei. Australian Journal of Ecology 7: 63–67. March.

Cameron, J. M.R. 2006 The Millendon Memoirs: George Fletcher Moore’s Western Australian Diaries and Letters, 1830-1841. Victoria Park: Hesperian Press.

Cameron, J.M.R. and P. Barnes (eds.) 2014 Lieutenant Bunbury’s Australian Sojourn: the letters and journals of Lieutenant H.W. Bunbury, 21st Royal North British Fusiliers, 1834-1837. Victoria Park, WA: Hesperian Press.

Campbell, M.E.; Mickelsen, O. Yang, M.G. Laquueur, G.L and J.C. Keresztesy

Chem Centre WA 2009 & 2010 Personal communication with Ken Dods.

Chemical Branch of the Mines Department 1938, see under Annual Report.

Chemical Branch of the Mines Department 1939, see under Annual Report.

Clark, Dymphna (translator and editor) 1994 Baron Charles von Hugel New Holland Journal, November 1833-October 1834. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press at the Miegunyah Press in association with the State Library of New South Wales.

Clegg. A.J. 1973 ‘Composition and related nutritional and organoleptic aspects of palm oil,’ Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society (JAOCS) https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1007/BF02641365

Connell S. W. P. G. Ladd 1993 Pollination biology of Macrozamia riedlei—the role of insects. In D. W. Stevenson and N. J. Norstog [eds.], Proceedings of CYCAD 90, second international conference on cycad biology, Townsville, 1990, QLD, Australia, 96–102. Palm and Cycad Societies of Australia Ltd., Milton, QLD, Australia

Contos, N., Kearing, T.A., Murray Districts Aboriginal Association, Collard, L., and Palmer, D. 1998. Pinjarra Massacre Site Research and Development Project: Report for Stage 1. Murray Districts Aboriginal Association.

Cornish, Mark 2010 ‘Macrozamia sarcotesta (by-yu): a traditional food of the Noongar of southwestern Australia https://www.anthropologyfromtheshed.com/macrozamia-the-fermented-oil-fruit-of-southwestern-australia

Crosby, D. 2004 The Poisoned Weed: Plants Toxic to Skin (Oxford University Press).

Curr, E.M. The Australian Race: Its origin, languages, customs, place of landing in Australia, and the routes by which it spread itself over that continent. Vols. 1 & 2. Melbourne: Government Printer.

Daw, B., Walley, T. and Keighery, G. (1997). Bush Tucker Plants of the South West. Department of Conservation and Land Management, Western Australia.

Dench, A. 1994 ‘Nyungar’ in Thieberger, N. and W. McGregor Macquarie Aboriginal Words. Sydney: Macquarie University, New South Wales.

Douglas, Wilfred. H. 1976 The Aboriginal Languages of the South-West of Australia. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. Second edition.

Drummond, James 1836 Correspondence to the Editor. Published 18th June in The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal, p 710.

Drummond, J. 1839 Letter to Sir William Hooker, Kew Gardens, London. July 25.t

Drummond, J. 1842 Letter No. 6 to the Inquirer, 10th August.

Drummond, J. 1843 Letter No. 15 to the Inquirer. 22nd March.

Drummond, H. 1862. ‘Useful plants of Western Australia.’ The Technologist 2: 25–28.

Duchess of Hamilton, Jill. and Bruce, Julia 1998 The Flower Chain: The Early Discovery of Australian Plants. Sydney: Kangaroo Press.

Edwards, H.H., 1894 Disease known as ‘Rickets’ or ‘Wobbles. ’The Journal of the Bureau of Agriculture of Western Australia 1(18): 225–234.

Gammage, B. 2012 The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Gott, B. 1982 ‘Ecology of root use by the Aborigines of southern Australia.’ Archaeology in Oceania, 17, pp. 59-67.

Green, N. 1979 Nyungar – The People: Aboriginal customs in the southwest of Australia. Mt Lawley, North Perth: Creative Research Publishers.

Grey, G., 1840 A Vocabulary of the Dialects of South Western Australia. London: T. and W. Boone.

Grey, G., 1841 Journals of Two Expeditions of Discovery in North-West Australia. London: T. and W. Boone.

Hall, J.A. and G.H. Walter 2013 ‘Seed dispersal of the Australian cycad Macrozamia miquelii (Zamiaceae): are cycads megafauna dispersed “grove forming” plants?’ American Journal of Botany, 100, 6: 1127-36).

Hall, J.A. and G.H. Walter 2014 ‘Relative Seed and Fruit Toxicity of the Australian Cycads Macrozamia miquelii and Cycas ophiolitic: Further evidence for a Megafaunal Seed Dispersal Syndrome in Cycads, and its Possible Antiquity,’ Journal of Chemical Ecology, 40, 8 (August): 860-868. New York.

Hallam. S.J. 1975 Fire and Hearth a Study of Aboriginal Usage and European Usurpation in South Western Australia. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. First edition.

Hallam, S. J. 1991 ‘Aboriginal Women as Providers: the 1830s on the Swan’ Aboriginal History, Vol. 15. Part 1. pp. 38-53.

Hallam, S.J. 2002 ‘Peopled landscapes in Southwestern Australia in the early 1800’s: Aboriginal burning off in the light of Western Australia historical documents.’ Early Days: Journal of the Royal Western Australian Historical Society, 12, 2: 177-191.

Hammond, J.E., 1933 Winjan’s People. Perth: Imperial Printing Co.

Hassell, A.Y. 1894 Notes and family papers. Manuscript. Perth: Battye Library.

Hassell, E.A. 1880-1890’s Notes and family papers. Perth: Battye Library. Handwritten manuscript.

Hassell, E., 1936 Notes on the ethnology of the Wheelman tribe of Southwestern Australia. Anthropos 31: 679–711.

Hassell, E., 1975 My Dusky Friends. Dalkeith: C.W. Hassell.

Harvey, A., 1945 ‘Food preservation in Australian tribes,’ Mankind 3(7): 191–192.

Hercock, M. Milentis, S. and P. Bianchi 2011 Western Australian Exploration 1836-1845: The letters, Reports and Journals of Exploration and Discovery in Western Australia. Victoria Park, WA: Hesperian Press.

Hill, K., 1984. Cycads of Australia. Australian Plants 13(4): 3-23.

Hill, Ken D.; Stevenson, D.W. and R. Osborne 2004 ‘The World List of Cycads’ The Botanical Review, Vol 70, Issue 2, April, pp. 274-298.

Ladd, P.G., S.W. Connell & B. Harrison, 1993. Seed toxicity in Macrozamia riedlei. In D.W. Stevenson & K.J. Norstog (eds.) The Biology, Structure, and Systematics of the Cycadales: Proceedings of CYCAD 90, The Second International Conference on Cycad Biology. Palm and Cycad Societies of Australia Ltd. Milton, Queensland, pp. 37–41.

Loaring, W.H. 1952 ‘Birds eating fleshy outer coat of zamia seeds’ WA Naturalist, Vol. 3, No. 4, March 15.

Lyon, R.M. 1833 ‘A Glance at the Manners, and Language of the Aboriginal Inhabitants of Western Australia; with a short vocabulary’. In N. Green (Ed.) Nyungar – The People: Aboriginal customs in the southwest of Australia. Perth: Creative Research Publishers.

Lythgoe, B. and N.V. Riggs 1949 J. Chem. Soc.: 2716.

Lyon, R.M. 1833 ‘A Glance at the Manners, and Language of the Aboriginal Inhabitants of Western Australia; with a short vocabulary.’ 23rd March in N. Green (ed.) 1979 Nyungar -The People: Aboriginal customs in the southwest of Australia. Perth: Creative Research.

Macintyre, Dobson and Associates 2003 Report on an Ethnographic, Ethnohistorical, Archaeological and Underwood Avenue Bushland Project Area, Shenton Park. A report prepared for the University of Western Australia.